روندا، ويلز

51°36′57″N 3°25′03″W / 51.615938°N 3.417521°W

Rhondda | |

|---|---|

Valley region | |

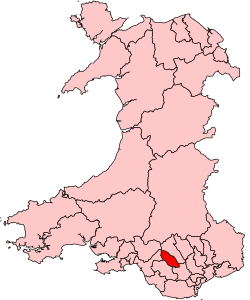

Map showing location of the Rhondda Valley within Wales | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Constituent country | Wales |

| County borough | Rhondda Cynon Taf |

| Parliamentary constituency | Rhondda |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 38٫59 ميل² (99٫94 كم²) |

| أعلى منسوب | 1٬935 ft (590 m) |

| التعداد (2011) | |

| • الإجمالي | 62٬545 |

| • الكثافة | 1٬600/sq mi (630/km2) |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+0 (Greenwich Mean Time) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+1 (British Summer Time) |

| Postal code | |

| مفتاح الهاتف | 01443 |

Rhondda /ˈrɒnðə/, or the Rhondda Valley (ويلزية: Cwm Rhondda [kʊm ˈr̥ɔnða]), is a former coalmining area in South Wales, previously in Glamorgan, now a local government district, of 16 communities around the River Rhondda. It embraces two valleys – the larger Rhondda Fawr valley (mawr large) and the smaller Rhondda Fach valley (bach small) – so that the singular "Rhondda Valley" and the plural are both commonly used. In 2001, the Rhondda constituency of the National Assembly for Wales had a population of 72,443;[2] while the Office for National Statistics counted the population as 59,602.[3] Rhondda forms part of Rhondda Cynon Taf County Borough and of the South Wales Valleys. It is most noted for its historical coalmining industry, which peaked between 1840 and 1925. The valleys produced a strong Nonconformist movement manifest in the Baptist chapels that moulded Rhondda values in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It is also famous for male voice choirs and in sport and politics.

Etymology

In the early Middle Ages, Glynrhondda was a commote of the cantref of Penychen in the kingdom of Morgannwg, a sparsely populated agricultural area. The spelling of the commote varied widely, as the Cardiff Records show:[4]

|

|

Many sources state the meaning of Rhondda as "noisy", though this is a simplified translation without research. Sir Ifor Williams, in his work Enwau Lleoedd, suggests that the first syllable rhawdd is a form of the Welsh adrawdd or adrodd, as in "recite, relate, recount", similar to the Old Irish rád; 'speech'.[4][5] The suggestion is that the river is speaking aloud, a comparison to the English expression "a babbling brook".[4]

With the increase in population from the mid-19th century the area was officially recognised as the Ystradyfodwg Local Government District, but was renamed in 1897 as the Rhondda Urban District after the River Rhondda.[6]

Residents of either valley rarely use the terms Rhondda Fach or Rhondda Fawr, referring instead to the Rhondda, or their specific village when relevant. Locals tend to refer to "The Rhondda" with a definite article not found on signposts and maps.

Early history

Prehistoric and Roman Rhondda: 8,000 BC – 410 AD

The Rhondda Valley is located in the upland, or Blaenau, area of Glamorgan. The landscape of the Rhondda was formed by glacial action during the last ice age, as slow-moving glaciers gouged out the deep valleys that exist today. With the retreat of the ice sheet, around 8000 BC, the valleys were further modified by stream and river action. This left the two river valleys of the Rhondda with narrow, steep-sided slopes which would dictate the layout of settlements from early to modern times.[7]

Mesolithic period

The earliest evidence of man's presence in these upper areas of Glamorgan was found in 1963 at Craig y Llyn. A small chipped stone tool found at the site, recorded as possibly being of Creswellian type or at least from the early Mesolithic period, places human activity on the plateau above the valleys.[8] Many other Mesolithic items have appeared in the Rhondda, mainly in the upper areas around Blaenrhondda, Blaencwm and Maerdy, and relating to hunting, fishing and foraging, which suggests seasonal nomadic activity. Though no definite Mesolithic settlements have been located, the concentration of finds at the Craig y Llyn escarpment suggests the presence of a temporary campsite in the vicinity.[9]

Neolithic period

The first structural relic of prehistoric man was excavated in 1973 at Cefn Glas near the watershed of the Rhondda Fach river. The remains of a rectangular hut with traces of drystone wall foundations and postholes was discovered; while carbon dating of charcoal found at the site dated the structure as late Neolithic.[8]

Bronze Age

Although little evidence of settlement has been found in the Rhondda for the Neolithic to Bronze Age periods, several cairns and cists have appeared throughout the length of both valleys. The best example of a round-cairn was found at Crug yr Afan, near the summit of Graig Fawr, west of Cwmparc. It consisted of an earthen mound with a surrounding ditch 28 metres in circumference and over 2 metres tall.[10] Although most cairns discovered in the area are round, a ring cairn or cairn circle exists on Gelli Mountain. Known as the Rhondda Stonehenge, it consists of ten upright stones no more than 60 cm in height, encircling a central cist.[11] All the cairns found within the Rhondda are located on high ground, many on ridgeways, and may have been used as waypoints.[11]

In 1912 a hoard of 24 late Bronze Age weapons and tools was discovered during construction work at the Llyn Fawr reservoir, at the source of the Rhondda Fawr. The items did not originate from the Rhondda and are thought to have been left at the site as a votive offering. Of particular interest are fragments of an iron sword, the earliest iron object to be found in Wales, and the only C-type Hallstatt sword recorded in Britain.[12]

Iron Age

With the exception of the Neolithic settlement at Cefn Glas, there are three certain pre-medieval settlement sites in the valley – Maendy Camp, Hen Dre'r Gelli and Hen Dre'r Mynydd. The earliest of these is Maendy Camp, a hillfort whose remains lie between Ton Pentre and Cwmparc.[13] Although its defences would have been slight, the camp made good use of the natural slopes and rock outcrops to its north-east face. It consisted of two earthworks: an inner and outer enclosure. When the site was excavated in 1901, several archaeological finds led to the camp being misidentified as Bronze Age. These finds, mainly pottery and flint knives, were excavated from a burial cairn discovered within the outer enclosure, but the site has since been classified as from the Iron Age.[13]

The settlement at Hen Dre'r Mynydd in Blaenrhondda was dated around the Roman period, when fragments of wheel-made Romano-British pottery were discovered. The site consists of a group of ruinous drystone roundhouses and enclosures, thought to have been a sheep-farming community.[14]

The most certain example of a Roman site in the area is found above Blaenllechau in Ferndale.[15] The settlement is one of a group of earthworks and indicates the presence of the Roman army during the 1st century AD. It was thought to be a military site or marching camp.[16]

Medieval Rhondda: AD 410–1550

The 5th century saw the withdrawal of Imperial Roman support from Britain, and succeeding centuries saw the emergence of national identity and of kingdoms. The area which would become the Rhondda lay within Glywysing, which incorporated the modern area of Glamorgan and was ruled by a dynasty founded by Glywys.[17] This dynasty was replaced by another founded by Meurig ap Tewdrig, whose descendant Morgan ap Owain would give Glamorgan its Welsh name Morgannwg.[18] With the coming of the Norman overlords after the 1066 Battle of Hastings, south-east Wales was divided into five cantrefi. The Rhondda lay within Penychen, a narrow strip running between modern-day Glyn Neath and the coast between Cardiff and Aberthaw. Each cantref was further divided into commotes, with Penychen made up of five such commotes, one being Glynrhondda.[19]

Relics of the Dark Ages are rare in the Glamorgan area and secular monuments still rarer. The few sites found have been located in the Bro, or lowlands, leaving historians to believe the Blaenau were sparsely inhabited, maybe only visited seasonally by pastoralists.[20] A few earthwork dykes are the only structural relics in the Rhondda area from this period. No carved stones or crosses exist to indicate the presence of a Christian shrine. In the Early Middle Ages, communities were split between bondmen, who lived in small villages centred on a court or llys of the local ruler to whom they paid dues, and freemen, with higher status, who lived in scattered homesteads. The most important village was the mayor's settlement or maerdref. Maerdy in the Rhondda Fach has been identified as such, mainly on the strength of the name, though the village did not survive past the Middle Ages.[20] The largest concentration of dwellings from the period, mainly platform houses, have been found around Gelli and Ystrad in the Rhondda Fawr.

During the late 11th century, the Norman lord, Robert Fitzhamon entered Morgannwg in an attempt to gain control of the area, building many earth and timber castles in the lowlands.[21] In the early 12th century Norman expansion continued, with castles being founded around Neath, Kenfig and Coity. In the same period Bishop Urban set up the Diocese of Llandaff under which Glynrhondda belonged to the large parish of Llantrisant.[22]

After the death of William, Lord of Glamorgan, his extensive holdings were eventually granted to Gilbert de Clare in 1217.[23] The subjugation of Glamorgan, begun by Fitzhamon, was completed by the powerful De Clare family.[24] Although Gilbert de Clare had now become one of the great Marcher Lords, the territory was far from settled. Hywel ap Maredudd, lord of Meisgyn captured his cousin Morgan ap Cadwallon and annexed Glynrhondda in an attempt to reunify the commotes under a single native ruler.[25] This conflict was unresolved by the time of De Clare's death and the area fell under royal control.

Settlements of medieval Rhondda

Little evidence exists of settlements within the Rhondda in the Norman period. Unlike the communal dwellings of the Iron Age, the remains of medieval buildings discovered in the area follow a pattern similar to modern farmsteads, with separate holdings spaced out around the hillsides. The evidence of medieval Welsh farmers comes from remains of their buildings, with the foundations of platform houses being discovered spaced out through both valleys.[26] When the sites of several platform houses at Gelligaer Common were excavated in the 1930s, potsherds from the 13th to 14th centuries were discovered.[27]

The Rhondda also has remains of two medieval castles. The older is Castell Nos,[28] located at the head of the Rhondda Fach overlooking Maerdy. The only recorded evidence of Castle Nos is a mention by John Leland, who stated, "Castelle Nose is but a high stony creg in the top of an hille". The castle comprises a scarp and ditch forming a raised platform and on the north face is a ruined dry-stone building. Its location and form do not appear to be Norman and it is thought to have been built by the Welsh as a border defence, which would date it before 1247, when Richard de Clare seized Glynrhondda.[29] The second castle is Ynysygrug, close to what is now Tonypandy town centre. Little remains of this motte-and-bailey earthwork defence, as much was destroyed when Tonypandy railway station was built in the 19th century.[30] Ynysygrug is dated around the 12th or early 13th century[30] and has been misidentified by several historians, notably Owen Morgan in his History of Pontypridd and Rhondda Valleys, who recorded it as a druidic sacred mound.[31] Iolo Morganwg erroneously believed it to be the burial mound of king Rhys ap Tewdwr.

The earliest Christian monument in the Rhondda is the shrine of St Mary at Penrhys, whose holy well was mentioned by Rhisiart ap Rhys in the 15th century.[32]

References

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Wales (2008) does not give the area of the Rhondda Valley, but gives it in hectares for each of the 16 communities as of 2001. Clydach (487 ha), Cymmer (355 ha), Ferndale (380 ha), Llwynypia (258), Maerdy (1064 ha), Pentre (581 ha), Penygraig (481 ha), Porth (370 ha), Tonypandy (337), Trealaw (286 ha), Trehafod (164 ha), Treherbert (2156 ha), Treorchy (1330 ha), Tylorstown (590 ha), Ynyshir (441 ha), Ystrad (714 ha). Total 9994 ha

- ^ "2001 Census of Population" (PDF). National Assembly of Wales. أبريل 2003. Retrieved 12 سبتمبر 2010.

- ^ "Key Statistics for urban areas in England and Wales" (PDF). National Assembly of Wales. Retrieved 12 سبتمبر 2010.

- ^ أ ب ت Hopkins (1975), p. 222.

- ^ Gwefen Cymru-Catalonia Kimkat.org

- ^ "Rhondda Urban District Council records". Archives Network Wales. Retrieved 19 فبراير 2009.

- ^ Davis (1989), p. 5.

- ^ أ ب Davis (1989), p. 7.

- ^ Williams, Glanmor, ed. (1984). Glamorgan County History, Volume II, Early Glamorgan: pre-history and early history. Cardiff: Glamorgan History Trust. p. 57. ISBN 0-904730-04-2.

- ^ Davis (1989), p. 11.

- ^ أ ب Davis (1989), p. 12.

- ^ Davis (1989), p. 9.

- ^ أ ب Davis (1989), p. 14.

- ^ Davis (1989), p. 15.

- ^ Davis (1989), p. 16.

- ^ Nash-Williams, V.E. (1959). The Roman frontier in Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- ^ Davis (1989), p. 17

- ^ Wendy Davis (1982), Wales in the Early Middle Ages (Studies in the Early History of Britain), Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7185-1235-4, p. 102.

- ^ William Rees (1951), An Historical Atlas of Wales from Early to Modern Times, Faber & Faber ISBN 0-571-09976-9

- ^ أ ب Davis (1989), p. 18.

- ^ Davis (1989), p. 19

- ^ Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments (in Wales), HMSO Glamorgan Inventories, Vol 3, part 2.

- ^ Pugh, T.B. (1971). Glamorgan County History, Volume III, The Middle Ages: The Marcher Lordships of Glamorgan and Morgannwg and Gower and Kilvey from the Norman Conquest to the Act of Union of England and Wales. University of Wales Press. p. 39.

- ^ Davies (2008), p. 746.

- ^ Pugh, T. B. (1971). Glamorgan County History, Volume III, The Middle Ages: The Marcher Lordships of Glamorgan and Morgannwg and Gower and Kilvey from the Norman Conquest to the Act of Union of England and Wales. University of Wales Press. p. 47.

- ^ Davis (1989), p. 22.

- ^ Aileen Fox (1939). Early Welsh Homesteads on Gelligaer Common, Glamorgan. Excavations in 1938. Glamorganshire. Vol. 94. Archaeologia Cambrensis. pp. 163–199.

- ^ Rhondda Cynon Taf Library Service, Digital Archive Archived 2008-10-03 at the Wayback Machine Picture of the remains of Castell Nos.

- ^ Davis (1989), p. 25.

- ^ أ ب Davis (1989), p. 26.

- ^ Davis (1989), p. 26, "Morgan not only misidentifies the height of the 30-ft. mound as 100 ft. but states that '...all these sacred mounds were reared in this country... when Druidism was the established religion', but gives no historic proof. The book also has an illustration of the castle to which the artist has added a moat and several druids, neither of which are factual."

- ^ John Ward (1914). 'Our Lady of Penrhys', Glamorganshire. Vol. 69. Archaeologia Cambrensis. pp. 395–405.

Bibliography

- قالب:Awdry-RailCo

- Carpenter, David J. (2000). Rhondda Collieries. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus Publishing. ISBN 0-7524-1730-4.

- Davies, John; Jenkins, Nigel (2008). The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-1953-6.

- Davis, Paul R. (1989). Historic Rhondda. Ynyshir: Hackman. ISBN 0-9508556-3-4.

- Hopkins, K.S. (1975). Rhondda Past and Future. Ferndale: Rhondda Borough Council.

- John, Arthur H. (1980). Glamorgan County History, Volume V, Industrial Glamorgan from 1700 to 1970. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Lewis, E.D. (1959). The Rhondda Valleys. London: Phoenix House.

- May, John (2003). Rhondda 1203 - 2003: The Story of the Two Valleys. Caerphilly: Castle Publications. ISBN 1-871354-09-9.

- Morgan, Prys (1988). Glamorgan County History, Volume VI, Glamorgan Society 1780 to 1980. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 0-904730-05-0.

- Smith, David (1980). Fields of Praise, The Official History of the Welsh Rugby Union 1881-1981. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 0-7083-0766-3.

- Williams, Chris (1996). Democratic Rhondda: politics and Society 1885-1951. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

External links

- Rhondda Valleys Information and History — The history of the Rhondda Valleys with high resolution mining photographs.

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- EngvarB from April 2021

- Use dmy dates from April 2021

- Pages using infobox settlement with no coordinates

- Articles containing ويلزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Pages with plain IPA

- Rhondda Valley

- Valleys of Rhondda Cynon Taf