حملة المائة زهرة

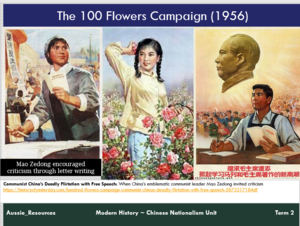

حملة المائة زهرة, وتسمى أيضاً حركة المائة زهرة (صينية: 百花齐放�), was a period from 1956 to 1957 in the People's Republic of China during which the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) encouraged citizens to openly express their opinions of the Communist Party.[1][2]

During the campaign, differing views and solutions to national policy were encouraged based on the famous expression by Mao: "The policy of letting a hundred flowers bloom and a hundred schools of thought contend is designed to promote the flourishing of the arts and the progress of science."[3] The movement was in part a response to the demoralization of intellectuals, who felt estranged from the Communist Party.[4] After this brief period of liberalization, the crackdown continued through 1957 and 1959 as an Anti-Rightist campaign against those who were critical of the regime and its ideology. Citizens were rounded up in waves by the hundreds of thousands, publicly criticized, and condemned to prison camps for re-education through labor, or even execution.[5] The ideological crackdown re-imposed Maoist orthodoxy in public expression, and catalyzed the Anti-Rightist Movement.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الحملة

التسمية

The name of the movement originated in a poem:

百花齊放,百家爭鳴 |

Let a hundred flowers bloom; let a hundred schools of thought contend. |

Mao had used this to signal what he had wanted from the intellectuals of the country, for different and competing ideologies to voice their opinions about the issues of the day. He alluded to the Warring States period when numerous schools of thought competed for ideological, not military, supremacy. Historically, Confucianism, Chinese Mahayana Buddhism and Taoism had gained prominence, and socialism would now face its test.[بحاجة لمصدر]

الإطلاق (أواخر 1956–مطلع 1957)

The campaign publicly began in late 1956. In the opening stage of the movement, issues discussed were relatively minor and unimportant in the grand scheme. The Central Government did not receive much criticism, although there was a significant rise in letters of conservative advice. Premier Zhou Enlai received some of these letters, and once again realized that, although the campaign had gained notable publicity, it was not progressing as had been hoped. Zhou approached Mao about the situation, stating that more encouragement was needed from the central bureaucracy to lead the intellectuals into further discussion.

Mao Zedong found the concept interesting and had superseded Zhou to take control. The idea was to have intellectuals discuss the country's problems in order to promote new forms of arts and new cultural institutions. Mao also saw this as the chance to promote socialism, believing that after discussion it would be apparent that socialist ideology was the dominant ideology over capitalism, even amongst non-communist Chinese, and would thus propel the development and spread of the goals of socialism.

The beginning of the Hundred Flowers Movement was marked by a speech titled On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People, published on 27 February 1957, in which Mao displayed open support for the campaign. The speech encouraged people to vent their criticisms as long as they were "constructive" (i.e., "among the people") rather than "hateful and destructive" (i.e., "between the enemy and ourselves").[6]

Our society cannot back down, it could only progress...criticism of the bureaucracy is pushing the government towards the better.[6]

الربيع (1957)

By the spring of 1957, Mao had announced that criticism was "preferred" and had begun to mount pressure on those who did not turn in healthy criticism on policy to the Central Government. The reception was immediate with intellectuals, who began voicing concerns without any taboo. In the period from 1 May to 7 June that year, millions of letters were pouring into the Premier's Office and other authorities.

From May to June 1957, newspapers published a huge range of critical articles.[7] The majority of these critiques argued that the Party had become less revolutionary and more bureaucratic.[7] Nonetheless, most of the commentary was premised on complete acceptance of socialism and the legitimacy of the Communist Party and focused on making the existing socialist system work better.[7]

People spoke out by putting up posters around campuses, rallying in the streets, holding meetings for CPC members, and publishing magazine articles. For example, students at Peking University created a "Democratic Wall" on which they criticized the CPC with posters and letters.[8]

They protested CPC control over intellectuals, the harshness of previous mass campaigns such as that against counter-revolutionaries, the slavish following of Soviet models, the low standards of living in China, the proscription of foreign literature, economic corruption among party cadres, and the fact that 'Party members [enjoyed] many privileges which make them a race apart'.[8]

آثار الحملة

In July 1957, Mao ordered a halt to the campaign. Unexpected demands for power sharing led to the abrupt change of policy.[9] By that time, Mao had witnessed Nikita Khrushchev denouncing Joseph Stalin and the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, events which he felt threatening. Mao's earlier speech, On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People, was significantly changed and appeared later on as an Anti-Rightist piece in itself.

The campaign made a lasting impact on Mao's ideological perception. Mao, who is known historically to be more ideological and theoretical, less pragmatic and practical, continued to attempt to solidify socialist ideals in future movements, and in the case of the Cultural Revolution, employed more violent means. Another consequence of the Hundred Flowers Campaign was that it discouraged dissent and made intellectuals reluctant to criticize Mao and his party in the future. The Anti-Rightist Movement that shortly followed, and was possibly caused by the Hundred Flowers Campaign, resulted in the persecution of intellectuals, officials, students, artists, and dissidents labeled "rightists."[10] The campaign led to a loss of individual rights, especially for any Chinese intellectuals educated in Western centers of learning.

The Hundred Flowers Movement was the first of its kind in the history of the People's Republic of China in that the government opened up to ideological criticisms from the general public. Although its true nature has always been questioned by historians, it can be generally concluded that the events that took place alarmed the central communist leadership. The movement also represented a pattern that has emerged from Chinese history wherein free thought is promoted by the government, and then suppressed by it. A similar surge in ideological thought would not occur again until the late 1980s, leading up to the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. The latter surge, however, did not receive the same amount of government backing and encouragement.

Another important issue of the campaign was the tension that surfaced between the political center and national minorities. With criticism allowed, some of the minorities' activists made public their protest against "Han chauvinism" which they saw the informal approach of party officials toward the local specifics.[11]

الخلاف حول نوايا الحملة

Historians debate whether Mao's motivations for launching the campaign were genuine. Some find it possible that Mao originally had pure intentions, but later decided to utilize the opportunity to destroy criticism. Historian Jonathan Spence suggests that the campaign was the culmination of a muddled and convoluted dispute within the Party regarding how to address dissent.[12]

Authors Clive James and Jung Chang posit that the campaign was, from the start, a ruse intended to expose rightists and counter-revolutionaries, and that Mao Zedong persecuted those whose views were different from those of the Party. The first part of the phrase from which the campaign takes its name is often remembered as "let a hundred flowers bloom." This is used to refer to an orchestrated campaign to flush out dissidents by encouraging them to show themselves as critical of the regime, and then subsequently imprison them, according to Chang and James.

In Mao: The Unknown Story by Jung Chang and Jon Halliday, Chang asserts that "Mao was setting a trap, and...was inviting people to speak out so that he could use what they said as an excuse to victimise them."[13] Prominent critic Harry Wu, who as a teenager was a victim, later wrote that he "could only assume that Mao never meant what he said, that he was setting a trap for millions."[14]

Mao's personal physician, Li Zhisui, suggested that:[15]

[The campaign was] a gamble, based on a calculation that genuine counterrevolutionaries were few, that rebels like Hu Feng had been permanently intimidated into silence, and that other intellectuals would follow Mao's lead, speaking out only against the people and practices Mao himself most wanted to subject to reform.

Professor Lin Chun characterizes the argument that the Hundred Flowers campaign was a calculated trap as a "conspiracy theory."[9] In her analysis, the "conspiracy theory" is disputed by empirical research from archival sources and oral histories.[9] She writes that many interpretations of the Hundred Flowers campaign "underestimate the fear on the part of Mao and party leadership over an escalating atmosphere of anticommunism within the communist world in the aftermath of the East European uprisings."[9]

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

- ^ MacFarquhar, Roderick. 1960. The Hundred Flowers. pp. 3

- ^ "Hundred Flowers Campaign." Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ "Definition of Hundred Flowers". Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved 2012-05-17.[dead link]

- ^ "Double-Hundred Policy (1956-1957)". chineseposters.net. Archived from the original on 2017-02-12. Retrieved 2017-02-11.

- ^ Short, Philip (2000). Mao: A Life. Macmillan. pp. 457–471. ISBN 978-0-8050-6638-8.

- ^ أ ب On the Correct Handling of the Contradictions Among the People

- ^ أ ب ت Karl, Rebecca E. (2010). Mao Zedong and China in the twentieth-century world : a concise history. Durham [NC]: Duke University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-8223-4780-4. OCLC 503828045.

- ^ أ ب Spence, Jonathan D. 1990. The Search For Modern China (2nd ed.) New York: W.W. Norton Company. pp. 539–43.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Lin, Chun (2006). The transformation of Chinese socialism. Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-8223-3785-0. OCLC 63178961.

- ^ Link, Perry. 23 July 2007. "Legacy of a Maoist Injustice Archived 2021-11-09 at the Wayback Machine." The Washington Post. p. A19.

- ^ Teiwes, cited in MacFarquhar, ed. The Politics of China, 1949-1989, p. 53.

- ^ Spence, Jonathan D. 2013. The Search for Modern China. New York: Norton. ISBN 9780393934519. pp. 508–13.

- ^ Jung Chang; Jon Halliday. Mao: The Unknown Story. Jonathan Cape. p. 435.

- ^ Harry Wu; Hongda Harry Wu; George Vecsey (2002). Troublemaker: One Man's Crusade Against China's Cruelty. NewsMax Media, Inc. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-9704029-9-8. Archived from the original on 2014-07-22. Retrieved 2016-09-20.

- ^ Zhisui Li (1996). "1957-1965". The Private Life of Chairman Mao. Chatto & Windus, Ltd. pp. 198–199. ISBN 978-0679764434. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

الأعمال المذكورة

- MacFarquhar, Roderick. 1960. The Hundred Flowers, Paris: The Congress for Cultural Freedom.

- 1973. The Origins of the Cultural Revolution: Contradictions Among the People, 1956-1957. Columbia University Press.

- Spence, Jonathan D. 2013. The Search for Modern China. New York: Norton. ISBN 9780393934519.

- Meisner, Maurice. 1986. Mao's China and After: A History of the People's Republic. New York: Macmillan. pp. 177–80.

- Zheng, Zhu. 1998. 1957 nian de xiaji: Cong bai jia zhengming dao liang jia zhengming. Zhengzhou: Henan renmin chubanshe.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

وصلات خارجية

- Articles containing صينية-language text

- Articles with dead external links from September 2022

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- مقالات تحتوي نصوصاً باللغة الصينية المبسطة

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2023

- حملات الحزب الشيوعي الصيني

- Anti-Rightist Campaign

- 1956 في الصين

- 1957 في الصين

- Maoist terminology

- Maoist China

- Persecution of intellectuals