حكام وين

Nguyễn lords 主阮 Chúa Nguyễn | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1558–1802 | |||||||||

Heirloom seal (from 1709) | |||||||||

Map showed the division of Vietnam territory among Nguyễn lords (green), Lê - Trịnh lords (purple), Mạc dynasty domain (pink) and Champa (yellow) in the Lê–Mạc War. | |||||||||

| الوضع | Duchy[مطلوب توضيح] within Lê dynasty of Đại Việt (1558 to 1789) Independent state (1789 -1802) | ||||||||

| العاصمة | Triệu Phong District (1558-1626) Phú Xuân (1636-1775) Hội An (1775-1777) Saigon (1777-1782; 1787-1802) | ||||||||

| اللغات المشتركة | Vietnamese | ||||||||

| الدين | Neo-Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism, Catholicism | ||||||||

| الحكومة | Feudal dynastic hereditary military dictatorship (1558–1777) Government in exile (1782–1787) Absolute Monarchy (1780–1802) | ||||||||

| Lords | |||||||||

• 1558–1613 | Nguyễn Hoàng (first) | ||||||||

• 1765–1777 | Nguyễn Phúc Thuần | ||||||||

• 1778–1802 | Nguyễn Phúc Ánh | ||||||||

| التاريخ | |||||||||

• تأسست | 1558 | ||||||||

• انحلت | 1802 | ||||||||

| العملة | Copper-alloy and zinc cash coins | ||||||||

| |||||||||

جزء من سلسلة عن |

|---|

| تاريخ ڤيتنام |

|

| خط زمني |

The Nguyễn lords (قالب:Vie, 主阮; 1558–1802),[أ] also known as the Nguyễn clan, were rulers of Đàng Trong (Inner Realm) in Central and Southern Vietnam, as opposed to Đàng Ngoài or Outer Realm, ruled by the Trịnh lords.[2]

While they recognized and claimed to be loyal subjects of the Later Lê dynasty, they were de facto rulers of Cochinchina. Meanwhile, the Trịnh lords ruled northern Vietnam, where the Lê Emperor remained a puppet figure.[3][4] They fought a long, bitter war that lasted 45 years that separated Vietnam into two polities for nearly two centuries. After the Tây Sơn wars, their descendants would finally rule over the whole of Vietnam as the Nguyễn dynasty and posthumously elevated their titles to emperors. Their rule consolidated earlier southward expansion into Champa and push into Cambodia.[5]

Origin

The Nguyễn lords traced their descent from a powerful clan originally based in Thanh Hóa Province. The clan supported Lê Lợi in his successful war of independence against the Ming dynasty. From that point on, the Nguyễn were one of the major noble families in Vietnam. Perhaps the most famous Nguyễn from this time was Nguyễn Thị Anh, the queen-consort for nearly 20 years (1442–1459).

Nguyễn Kim restores Lê dynasty

In 1527, Mạc Đăng Dung replaced the last Lê emperor Lê Cung Hoàng and established a new dynasty (Mạc dynasty). The Trịnh and Nguyễn lords returned to Thanh Hóa province and refused to accept the rule of the Mạc. All of the region south of the Red River was under their control, but they were unable to conquer Đông Đô for many years. During this time, the Nguyễn–Trịnh alliance was led by Nguyễn Kim; his daughter Nguyễn Thị Ngọc Bảo was married to the Trịnh clan leader, Trịnh Kiểm.

Trịnh seizes the power of Lê dynasty

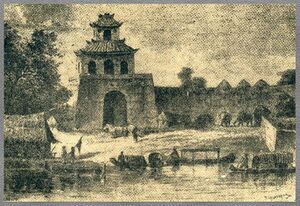

After restoring Lê dynasty in 1533, Nguyễn Kim become the head of the government while emperor Lê Trang Tông was used as the figurehead of the state. Dương Chấp Nhất, the former Mạc dynasty's mandarin that was governing Tây Đô fortress in Thanh Hoa province decided to surrender to Lê dynasty when Nguyễn Kim recaptured this province in 1543.

After seizing Tây Đô citadel and onward marching to attack Ninh Bình. In 20/5/1545, Dương Chấp Nhất invited Kim to visit his military camp. In the hot temperature of summer, Dương Chấp Nhất treated Kim with watermelon. After the party, Kim felt ill after return home and died in same day. Dương Chấp Nhất later returned to Mạc dynasty.

After the death of Kim, The government starts to turn into chaos. The successor of the head of government was intentionally inherited by Kim's eldest son, Nguyễn Uông, however , Uông was secretly assassinated by his brother-in -law (Trịnh Kiểm) and Trịnh Kiểm later took control of the government.

According to the records of Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư, Đại Nam thực lục both suggested that Dương Chấp Nhất tried to assassinate the emperor Lê Trang Tông by pretending to surrender. However the plot was unsuccessful, then he changed the target to Nguyễn Kim, who was in charge of power and military.

Nguyễn Hoàng as the governor of Thuận Hóa and Quảng Nam province

The second son of Kim, Nguyễn Hoàng fears that his fate will be like his brother; therefore, he tried to run away from the capital to avoid the next assassination. Later, he asks his sister Nguyễn Thị Ngọc Bảo (wife of Trịnh Kiểm) to ask Kiểm to appoint him to be the governor of far-south frontier of Đại Việt, Thuận Hóa (modern Quảng Bình to Quảng Nam provinces), in what used to be Kingdom of Champa land before 1306. Thuận Hóa was still regarded as uncivilised land and simultaneously, Trịnh Kiểm also would like to remove the power and influence of Nguyễn Hoàng in the capital city so he agreed with the proposal.

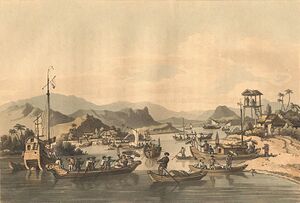

In 1558, Nguyễn Hoàng and family and his loyal generals move to Thuận Hóa to take his position by boat. Arriving at Triệu Phong District, he started to make this place the capital and build the new palace.

In March 1568, Emperor Lê Anh Tông summons Hoàng for the meeting at Tây Đô and meet Trịnh Kiểm at his personal mansion. Kiểm begins to trust the loyalty of Nguyễn Hoàng so he appoints Hoàng to become the governor of Quảng Nam

In 1636, The capital was moved to new city of Phú Xuân (modern Huế), the Nguyễn lord, under Nguyễn Hoàng, slowly expanded their control to the south while the Trịnh lords continued their war with Mạc dynasty for control over the north of Vietnam.

Trịnh - Nguyễn alliance defeat Mạc dynasty

In 1592, Đông Đô (Hanoi) was recaptured by the Trịnh - Nguyễn army under Trịnh Tùng and the Mạc Emperor was executed. The remnant Mạc clan fled to Cao Bằng to reinstall their own regime until defeated in 1677. The next year, Nguyễn Hoàng came north with an army and money to help defeat the remainder of the Mạc clan.

تصاعد التوتر

In 1600, a new Lê emperor took the throne, Lê Kính Tông. Just like the previous Lê emperors, was a powerless figurehead under the control of Trịnh Tùng. Besides that, a revolt broke out in Ninh Bình Province, "possibly instigated by the Trịnh". As a consequence of these events, Nguyễn Hoàng formally broke off relations with the Court, rightly arguing that it was the Trịnh who ruled, not the Lê emperor. This uneasy state of affairs continued for the next 13 years until Nguyễn Hoàng died in 1613. He had ruled the southern provinces for 55 years.

His successor, Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên, continued Nguyễn Hoàng's policy of essential independence from the Court in Hanoi. He initiated friendly relations with the Europeans who were now sailing into the area. A Portuguese trading post was set up in Hội An. By 1615 the Nguyễn were producing their own bronze cannons with the aid of Portuguese engineers. In 1620 the emperor was removed from power and executed by Trịnh Tùng. Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên formally announced that he would not be sending any tax to the central government nor did he acknowledge the new Emperor as the Emperor of the country. Tensions rose over the next seven years till open warfare broke out in 1627 with the next successor of the Trịnh, Trịnh Tráng.

The war lasted until 1673 when peace was declared. The Nguyễn was not only fought off the Trịnh attacks but also continued their expansion southwards along the coast, though the war slowed this expansion. Around 1620, Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên's daughter married Chey Chettha II, a Khmer king. Three years later, 1623, the Nguyễn formally gained permission for Vietnamese to settle in Prei Nokor, which was later reborn as the city of Saigon.

When the war with the Trịnh ended, the Nguyễn were able to put more resources into pushing suppression of the Champa kingdoms and conquest of lands which used to belong to the Khmer Empire.

The Dutch brought Vietnamese slaves they captured from Nguyễn lord territories in Quảng Nam Province to their colony in Taiwan.[6]

The Nguyen lord Nguyen Phuc Chu had referred to Vietnamese as "Han people" 漢人 (Hán nhân) in 1712 when differentiating between Vietnamese and Chams.[7] The Nguyen Lords established đồn điền after 1790. It was said "Hán di hữu hạn" 漢夷有限 ("the Vietnamese and the barbarians must have clear borders") by the Gia Long Emperor (Nguyễn Phúc Ánh) when differentiating between Khmer and Vietnamese.[8]

Trousers and tunics on the Chinese pattern in 1774 were ordered by the Vo Vuong Emperor to replace the sarong type Vietnamese clothing.[9] The Chinese Ming dynasty, Tang dynasty, and Han dynasty clothing was ordered to be adopted by Vietnamese military and bureaucrats by the Nguyen Lord Nguyễn Phúc Khoát (Nguyen The Tong).[10] Pants were mandated by the Nguyen in 1744 and the Cheongsam Chinese clothing inspired the Ao Dai.[11] Chinese clothing started having an impact on Vietnamese dress in the Ly dynasty. The current Ao Dai was introduced by the Nguyen Lords.[12] Cham provinces were seized by the Nguyen Lords.[13] Provinces and districts originally belonging to Cambodia were taken by Vo Vuong.[14][15]

Wars over the south

In 1714, Nguyễn sent an army into Cambodia to support Keo Fa's claim to the throne against Prea Srey Thomea (see also, Dark ages of Cambodia). Siam joined in siding with the Prea Srey Thomea against the Vietnamese claimant. At Bantea Meas, the Vietnamese routed the Siamese armies, but by 1717 the Siamese had gained the upper hand. The war ended with a negotiated settlement, whereby Keo Fa was allowed to take the Cambodia crown in exchange for his allegiance to Siam.[16] For their part, the Nguyễn lords wrested more territory from the weakened Cambodian kingdom.

Two decades later, in 1739, the Cambodians attempted to reclaim the lost coastal land. The fighting lasted some ten years, but the Vietnamese fended off the Cambodian raids and secured their hold on the rich Mekong Delta.[17]

With Siam embroiled in war with Burma, the Nguyễn mounted another campaign against Cambodia in 1755 and conquered additional territory from the ineffective Cambodian court. At the end of the war the Nguyễn had secured a port on the Gulf of Siam (Hà Tiên) and were threatening Phnom Penh itself.

Under a new king Phraya Taksin, the Siamese reasserted its protection of its eastern neighbor by coming to the aid of the Cambodian court. War was launched against the Nguyễn in 1769. After some early success, the Nguyễn forces by 1773 were facing internal revolts and had to abandon Cambodia to deal with the civil war in Vietnam itself. The turmoil gave rise to the Tây Sơn.

The fall of the Nguyễn lords in 1777

Vietnamese nobleman and wife from Quảng Nam (Đàng Trong) in 1595.

In 1771, as a result of heavy taxes and defeats[بحاجة لمصدر] in the war with Cambodia, three brothers from Tây Sơn sparked a peasant uprising that quickly engulfed much of southern Vietnam. Within two years, the Tây Sơn brothers captured the provincial capital Qui Nhơn. In 1774, the Trịnh in Hà Nội, seeing their rival gravely weakened, ended the hundred-year truce and launched an attack of the Nguyễn from the north. The Trịnh forces quickly overran the Nguyễn capital in 1774, while the Nguyễn lords fled south to Saigon. The Nguyễn fought on against both the Trịnh army and the Tây Sơn, but their effort was in vain. By 1777, Saigon was captured and nearly the entire Nguyễn Phúc family was killed, all except one nephew, Nguyễn Ánh, who managed to flee to Siam.

Restored (1778-1802) and unification war of Vietnam

Nguyễn Ánh did not give up, and in 1780 he attacked the Tây Sơn army with a new army from Siam (he was allied with King Taksin). However, Taksin went insane and was killed in a coup. The new king of Siam, Chulaloke, had more urgent affairs than helping Nguyễn Ánh retake Vietnam and so this campaign faltered. The Siamese army retreated, and Nguyễn Ánh went into exile, but would later return.

Nguyễn foreign relations

The Nguyễn were significantly more open to foreign trade and communication with Europeans than the Trịnh. According to Dupuy, the Nguyễn were able to defeat initial Trịnh attacks with the aid of advanced weapons they purchased from the Portuguese (see Artillery of the Nguyễn lords for more details). The Nguyễn also conducted fairly extensive trade with Japan and China.[18]

The Portuguese set up a trade center at Faifo (present day Hội An), just south of Huế in 1615. However, with the end of the great war between the Trịnh and the Nguyễn, the need for European military equipment declined. The Portuguese trade center never became a major European base (unlike Goa or Macau).

In 1640, Alexandre de Rhodes returned to Vietnam, this time to the Nguyễn court at Huế. He began work on converting people to the Catholic faith and building churches. After six years, the Nguyễn Lord, Nguyễn Phúc Lan, came to the same conclusion as Trịnh Tráng had, that de Rhodes and the Catholic Church represented a threat to their rule. De Rhodes was condemned to death but he was allowed to leave Vietnam on pain of death were he to return.

[19] Quảng Nam Province was the site where fourth rank Chinese Brigade Vice-Commander (Dushu) Liu Sifu was shipwrecked after being blown by the wind and he was taken back to Guangzhou, China by a Vietnamese Nguyễn ship in 1669. The Vietnamese sent the Chinese Zhao Wenbin to led the diplomatic delegation on the ship and requested establishment of commercial links but the request was rejected despite Qing Chinese officials thanking the Nguyễn for repatriating the shipwrecked military officer.[20] On Champa's coastal waters in a place called Linlangqian by the Chinese a ship ran aground after departing on 25 Jun 1682 from Cambodia carrying Chinese captain Chang Xiaoguan with a Chinese crew. Their cargo was left in the waters Chen Xiaoguan went to Thailand (Siam). This was recorded in the log of a Chinese trading junk going to Nagasaki on 25 June 1683.[21][22]

قائمة حكام وين

- Nguyễn Kim: he is the founder of Nguyen lords but he never claimed himself as Nguyen Lord, hence he is not considered as the first Nguyen Lord

- Nguyễn Hoàng 1558–1613: the first Nguyen Lord

- وين فوك وين 1613–1635

- Nguyễn Phúc Lan 1635–1648

- Nguyễn Phúc Tần 1648–1687

- Nguyễn Phúc Thái 1687–1691

- Nguyễn Phúc Chu 1691–1725

- Nguyễn Phúc Thụ 1725–1738

- Nguyễn Phúc Khoát 1738–1765

- Nguyễn Phúc Thuần 1765–1777

- Nguyễn Phúc Dương 1776–1777 (co-ruled with Nguyễn Phúc Thuần)

- Nguyễn Phúc Ánh 1778-1802

| سبقه Mạc dynasty |

Ruler of southern Vietnam 1533–1777 |

تبعه Tây Sơn dynasty |

Family tree

| Nguyễn lords family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Notes:

Reference: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- List of Vietnamese dynasties

- Nguyen, the surname

Notes

Citations

- ^ Phạm Cao Phong (Gửi cho BBC từ Paris) (4 September 2015). "Bảo Đại trao kiếm giả cho 'cách mạng'? Mùa thu năm trước Bảo tàng Lịch sử Việt Nam mang chuông sang gióng ở thủ đô Pháp" (in الفيتنامية). BBC News (British Broadcasting Corporation, Government of the United Kingdom). Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Taylor (1995), p. 170: "The 'Kingdom of Cochinchina' was the polity of the Nguyễn lords (chúa), who had become the more and more independent rivals of the Trịnh lords of the north – if not of the Lê emperors whose affairs the Trịnh lords managed..."

- ^ Pelley (2002), p. 216: "This fragmentation became more pronounced in the mid-sixteenth century when a distinctly bifurcated pattern of politics arose, with the Trịnh lords in the North and the Nguyễn lords in the South."

- ^ Chapuis (1995), p. 119ff.

- ^ Hardy (2009), p. 61: "Vietnam's southward expansion as it took place before the period of the Nguyễn Lords ..."

- ^ Mateo (2009), p. 125.

- ^ Wong Tze Ken (2004).

- ^ Choi Byung Wook (2004), p. 34.

- ^ Reid (9 May 1990), p. 90.

- ^ Werner (21 August 2012), p. 295.

- ^ Ao Dai (2018).

- ^ Vietnamese Ao Dai (2019).

- ^ Bridgman (1847), p. 584.

- ^ Coedes (1966), p. 213.

- ^ Coedes (2015), p. 175.

- ^ Kohn (1999), p. 445.

- ^ Aung-Thwin (13 May 2011), p. 158.

- ^ Khoang (2001), pp. 414–425.

- ^ Liu, Shiuh-feng. (2013). "Shipwreck Salvage and Survivors' Repatriation Networks of the East Asian Rim in the Qing Dynasty". In Kayoko, Fujita; Momoki, Shiro; Reid, Anthony (eds.). Offshore Asia: Maritime Interactions in Eastern Asia before Steamships. Vol. 18 of Nalanda-Sriwijaya series (illustrated, reprint ed.). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 211–235. ISBN 978-9814311779. Archived from the original on 2017.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|archive-date=(help) - ^ Wong, Danny Tze-Ken (2018). "The Chinese Factor in the Shaping of the Nguyen Rule over Southern Vietnam during the 17th & 18th Centuries". In Wade, Geoff; Chin, James K. (eds.). China and Southeast Asia: Historical Interaction. Routledge Studies in the Modern History of Asia (illustrated ed.). Singapore: Routledge, Singapore University Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0429952128.

- ^ Ishii, Yoneo, ed. (1998). "25 June 1683". The Junk Trade from Southeast Asia: Translations from the Tôsen Fusetsu-gaki, 1674-1723. Vol. 188 of Book Monograph (illustrated ed.). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 29. ISBN 9812300228. Archived from the original on 2017.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|archive-date=(help) - ^ Benjamin, Geoffrey; Chou, Cynthia, eds. (2002). Tribal Communities in the Malay World: Historical, Cultural, and Social Perspectives. Vol. 106 of Lectures, Workshops, and Proceedings of International Conferences (reprint ed.). Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 29. ISBN 9812301666.

References

- "Ao Dai". Vietnam Online. Vietnam Online.com. 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- Aung-Thwin, Michael Arthur; Hall, Kenneth R. (13 May 2011). New Perspectives on the History and Historiography of Southeast Asia: Continuing Explorations. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-81964-3.

- Bridgeman, Elijah Coleman; Williams, Samuel Wells (1847). The Chinese Repository. Proprietors.

- Chapuis, Oscar (1995). A History of Vietnam: From Hong Bang to Tu Duc. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313296222. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- Choi Byung Wook (2004). Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820–1841): Central Policies and Local Response. SEAP Publications. ISBN 978-0-87727-138-3.

- Coedes, George (1966). The Making of South East Asia. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05061-7.

- Coedes, George (2015). The Making of South East Asia (RLE Modern East and South East Asia). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-45094-8.

- Hardy, Andrew David; Cucarzi, Mauro; Zolese, Patrizia (2009). Champa and the Archaeology of Mỹ Sơn (Vietnam).

- Khoang, Phan (2001). Việt sử xứ Đàng Trong (in الفيتنامية). Hanoi: Văn Học Publishing House.

- Kohn, George Childs (1999). Dictionary of Wars Revised Edition. Facts on File.

- Mateo, José Eugenio Borao (2009). The Spanish Experience in Taiwan 1626–1642: The Baroque Ending of a Renaissance Endeavour (illustrated ed.). Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-9622090835.

- Pelley, Patricia M. (2002). Postcolonial Vietnam: New Histories of the National Past.

- Reid, Anthony (9 May 1990). Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450–1680: The Lands Below the Winds. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-04750-9.

- Taylor, Keith Weller and John K. Whitmore (1995). Essays into Vietnamese Pasts.

- "Vietnamese Ao Dai: From Dong Son Bronze Drum to Int'l Beauty Contests". VIETNAM BREAKING NEWS. Vietnam Breaking News. 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- Werner, Jayne; Whitmore, John K.; Dutton, George (21 August 2012). Sources of Vietnamese Tradition. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-51110-0.

- Wong Tze Ken, Danny (2004). "Vietnam-Champa Relations and the Malay-Islam Regional Network in the 17th–19th Centuries". Internet Archive Wayback Machine. Archived from the original on 2004-06-17. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- Dupuy, R. Ernest and Trevor N. (1993). The Encyclopedia of Military History. Harper & Row. ISBN 9780062700568.

General references

External links

- CS1 الفيتنامية-language sources (vi)

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing ڤيتنامية-language text

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تنظيف

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from February 2022

- Pages using infobox country or infobox former country with the symbol caption or type parameters

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2017

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Nguyễn lords

- 1558 establishments in Asia

- 1777 disestablishments in Asia

- Lords

- Positions of authority

- Titles of national or ethnic leadership

- 16th-century establishments in Vietnam