حرب الپلاتا

| حرب الپلاتا | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| جزء من الحرب الأهلية الأرجنتينية و الحرب الأهلية الأوروگوائية | |||||||

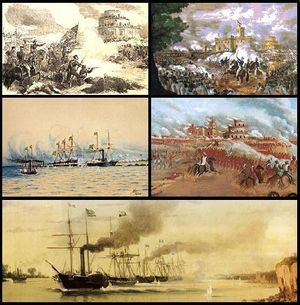

من أعلى لأسفل: Brazilian 1st Division in the Caseros; Uruguayan infantry aiding Entre Ríos cavalry in Caseros; Beginning of the Battle of The Tonelero Pass; Charge of Urquiza's cavalry in Caseros; Passage of Brazilian fleet at The Tonelero. | |||||||

| |||||||

| المتحاربون | |||||||

| القادة والزعماء | |||||||

| القوى | |||||||

| |||||||

| الضحايا والخسائر | |||||||

| 600+ dead and wounded |

| ||||||

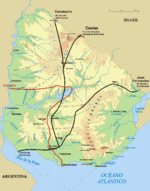

The Platine War (18 August 1851 – 3 February 1852) was fought between the Argentine Confederation and an alliance consisting of the Empire of Brazil, Uruguay, and the Argentine provinces of Entre Ríos and Corrientes. The war was part of a long-running dispute between Argentina and Brazil for influence over Uruguay and Paraguay, and hegemony over the Platine region (areas bordering the Río de la Plata). The conflict took place in Uruguay and northeastern Argentina, and on the Río de la Plata. Uruguay's internal troubles, including the long-running Uruguayan Civil War (La Guerra Grande – "The Great War"), were heavily influential factors leading to the Platine War.

In 1850, the Platine region was politically unstable. Although the Governor of Buenos Aires, Juan Manuel de Rosas, had gained dictatorial control over other Argentine provinces, his rule was plagued by a series of regional rebellions. Meanwhile, Uruguay struggled with its own civil war, which started after gaining independence from the Brazilian Empire in 1828 in the Cisplatine War. Rosas backed the Uruguayan Blanco party in this conflict, and further desired to extend Argentine borders to areas formerly occupied by the Spanish Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. This meant asserting control over Uruguay, Paraguay, and Bolivia. This threatened Brazilian interests and sovereignty since the old Spanish Viceroyalty had also included territories which had long been incorporated into the Brazilian province of Rio Grande do Sul.

Brazil actively pursued ways to eliminate the threat from Rosas. In 1851, it allied with the Argentine breakaway provinces of Corrientes and Entre Rios (led by Justo José de Urquiza), and the anti-Rosas Colorado party in Uruguay. Brazil next secured the south-western flank by signing defensive alliances with Paraguay and Bolivia. Faced with an offensive alliance against his regime, Rosas declared war on Brazil.

Allied forces first advanced into Uruguayan territory, defeating Rosas' Blanco party supporters led by Manuel Oribe. Afterwards, the Allied army was divided, with the main arm advancing by land to engage Rosas' main defenses and the other launching a seaborne assault directed at Buenos Aires.

The Platine War ended in 1852 with the Allied victory at the Battle of Caseros, for some time establishing Brazilian hegemony over much of South America. The war ushered in a period of economic and political stability in the Empire of Brazil. With Rosas gone, Argentina began a political process which would result in a more unified state. However, the end of the Platine war did not completely resolve issues within the Platine region. Turmoil continued in subsequent years, with internal disputes among political factions in Uruguay, a long civil war in Argentina, and an emergent Paraguay asserting its claims. Two more major international wars (see:Paraguayan War) followed during the next two decades, sparked by territorial ambitions and conflicts over influence.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Background

Rosas rule in Argentina

Don Juan Manuel de Rosas became governor of Buenos Aires after the brief period of anarchy following the end of the Cisplatine War in 1828. In theory, Rosas only held as much power as governors of the other Argentine provinces, but in reality he ruled over the entire Argentine Confederation, as the country was then known. Although he was one of the Federalists, a faction which demanded greater provincial autonomy, in practice Rosas exercised control over the other provinces and become the virtual dictator of Argentina.[ب][ت][6] During his 20-year government, the country witnessed the resurgence of armed conflicts between the Unitarians (his rival political faction) and the Federalists.[6][7][8]

Rosas desired to recreate the former Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. He aimed to build a powerful, republican state with Argentina placed at the center.[ث][ج][ح][خ][9][10] The defunct Viceroyalty had shattered into several separate nations following the Argentine War of Independence at the beginning of the 19th century. To achieve reunification, the Argentine government needed to annex the three neighboring countries – Bolivia, Uruguay and Paraguay, as well as to incorporate a portion of the southern region of Brazil.[11] Rosas first had to gather allies across the region who shared his vision. In some instances, this meant that he had to become involved in the internal politics of neighboring countries, backing those sympathetic to union with Argentina, and occasionally even financing rebellions and wars.[د][11]

Paraguay

Uruguayan conflict

The old Brazilian province of Cisplatina had become independent Oriental Republic of Uruguay after the Cisplatine War of the 1820s.[7] The country soon was engulfed in a long civil war between its two political parties: the Blancos, led by Don Juan Antonio Lavalleja, and the Colorados, led by Don Fructuoso Rivera.[7]

Empire of Brazil reacts

By the middle of the 19th century, the Empire of Brazil was the richest[12] and most powerful nation in Latin America.[13] It thrived under democratic institutions and a constitutional monarchy, and prided itself on the absence of the caudillos, dictators and coups d'état which were common across the rest of the continent.[ذ] During the minority of emperor Pedro II in the 1830s, however, there had been internal rebellions driven by local disputes for power within a few provinces.[14] One of these, the Ragamuffin War, had been led by Gonçalves, as noted above.

Alliance against Rosas

The Brazilian government set about creating a regional alliance against Rosas, sending a delegation to the region led by Honório Hermeto Carneiro Leão (later the Marquis of Paraná), who held plenipotentiary authority. He was assisted by José Maria da Silva Paranhos (later the Viscount of Rio Branco). Brazil signed a treaty with Bolívia in which Bolivia agreed to strengthen its border defenses to deter any attack by Rosas, though it declined to contribute troops to a war with Argentina.[15]

Stage 1 – Allied invasion of Uruguay

The Count of Caxias led a Brazilian army of 16,200 professional soldiers across the border between Rio Grande do Sul and Uruguay on 4 September 1851. His force consisted of four divisions, with 6,500 infantrymen, 8,900 cavalrymen, 800 artillerymen and 26 cannons,[16] a little under half the total Brazilian army (37,000 men);[17] while another 4,000 of his men remained in Brazil to protect its border.[16]

Stage 2 – Allied invasion of Argentina

Allied army advance

Shortly after the surrender of Oribe, the Allied forces split into two groups, the plan being for one force to maneuver upriver and sweep down on Buenos Aires from Santa Fe, while the other would make a landing at the port of Buenos Aires itself. The first of these groups, was composed of Uruguayan and Argentine troops, along with the 1st Division of the Brazilian Army under Brigadier General Manuel Marques de Sousa (later the Count of Porto Alegre). It was initially based in the town of Colonia del Sacramento in the south of Uruguay across the Río de la Plata estuary from the city of Buenos Aires.[18]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Rosas defeated

The Allied army had been advancing on the Argentinian capital of Buenos Aires by land, while the Brazilian Army commanded by Caxias planned a supporting attack by sea. On 29 January at the Battle of Alvarez Field the Allied vanguard defeated a force of 4,000 Argentines led by two colonels which General Ángel Pacheco had sent to slow down the advance.[19] Pacheco retreated. Two days later, troops under his personal command were defeated at the Battle of Marques Bridge by two allied divisions.[20] On 1 February 1852, the Allied troops encamped approximately nine kilometers from Buenos Aires. The next day a brief skirmish between the vanguards of both armies ended with a retreat by the Argentines.[21]

Aftermath

Brazil

The triumph in Caseros was a pivotal military victory for Brazil. The independence of Paraguay and Uruguay was secured, and the planned Argentine invasion of Rio Grande do Sul was blocked.[23] In a period of three years, the Empire of Brazil had destroyed any possibility of reconstituting a state encompassing the territories of old Viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata, a goal cherished by many in Argentina since independence.[24] Brazil's army and fleet had accomplished what Great Britain and France, the great powers of that time, had not achieved through interventions by their powerful navies.[25] This represented a watershed for the history of the region as it not only ushered in Imperial hegemony over the Platine region,[2][3] but, according to Brazilian historian J. F. Maya Pedrosa, also in the rest of South America.[13] The War of the Triple Alliance eighteen years later would only be a confirmation of Brazilian dominance.[ر]

Argentina

Soon after the Battle of Caseros the San Nicolás Agreement was signed. It was meant to comply with the constitutional mandate of the Federal pact that presided over the Argentine Confederation, convening a Constitutional Assembly to meet in Santa Fe. This agreement was not accepted by the province of Buenos Aires, since it reduced its influence and power over the other provinces. Following the revolution of 11 September 1852,[26][27] Buenos Aires seceded from the confederation, thus Argentina got divided into two rival, independent states which fought to establish dominance.[2][28] On the one side were the Federalists of the Argentine Confederation, led by Justo José de Urquiza. On the other, the Autonomists of Buenos Aires. The civil war was only brought to an end with the decisive victory of Buenos Aires over the Federation at the 1861 Battle of Pavón. The bonaerense liberal leader Bartolomé Mitre was elected the first President of a united Argentine Republic in 1862.[29][30]

Paraguay and Uruguay

With the opening of the Platine rivers, Paraguay now found it possible to contract with European technicians and Brazilian specialists to aid in its development. Unhindered access to the outside world also enabled it to import more advanced military technology.[31] During the greater part of the 1850s, the dictator Carlos López harassed Brazilian vessels attempting to freely navigate the Paraguay River. López feared that the province of Mato Grosso might become a base from which an invasion from Brazil could be launched. This dispute was also leverage with the Imperial government for acceptance of his territorial demands in the region.[32] The nation also experienced difficulties in delimiting its borders with Argentina which wanted the whole Gran Chaco region: a demand which Paraguay could not accept, as this would entail surrendering more than half of its national territory.[32]

Endnotes

- ^ "Brasil possuía uma reputação na comunidade internacional que, com a única exceção dos Estados Unidos da América, nenhum outro país americano tinha". See Lyra 1977, Vol 2, p. 9.

- ^ "He became governor of Buenos Aires in 1929. The city of Buenos Aires remained at the center of Argentine politics, but now as a provincial capital. In reaction to the chaos that the political wars of the 1820s had created, he instituted an authoritarian regime. [...] Rosas grew notorious for his repression of political opponents." —Daniel K. Lewis in Lewis 2001, p. 45.

- ^ "In the first half of the 19th century Juan Manuel de Rosas came to prominence as a caudillo in Buenos Aires province, representing the interests of rural elites and landowners. He became governor of the province in 1829 and, while he championed the Federalist cause, he also helped centralize political power in Buenos Aires and required all international trade to be funneled through the capital. His reign lasted more than 20 years (from 1829 to 1852), and he set ominous precedents in Argentine political life, creating the infamous mazorca (his ruthless political police force) and institutionalizing torture." —Danny Palmerlee in Palmerlee 2008, pp. 32–33.

- ^ "Rosas had never recognized Paraguay as an independent nation. He still called it the província del Paraguay and sought its 'recovery', aiming to extend its frontiers of the confederation to those of the old Spanish viceroyalty." —John Lynch in Lynch 2001, p. 140.

- ^ "A tentativa do ditador da Confederação Argentina, Juan Manuel de Rosas, na década de 1830, de se impor às antigas províncias do vice-reinado do Rio da Prata, abrigando–as em um Estado nacional sob sua chefia". —Francisco Doratioto in Doratioto 2002, p. 25.

- ^ "O ditador de Buenos Aires, Juan Manuel de Rosas, sonhou reconstituir o antigo vice-reinado do Prata, criado na segunda metade do século XVIII e que abrangia, além da Argentina, as atuais repúblicas do Uruguai, Paraguai e Bolívia (alto Peru)." —Manuel de Oliveira Lima in Lima 1989, p. 158.

- ^ "Cresceu, então, o velho receio do Paraguai, por que o objetivo de Rosas sempre foi reconstituir o Vice-Reinado." —J. F. Maya Pedrosa in Pedrosa 2004, p. 50.

- ^ "Deliberate manipulation of Uruguayan politics for external advantage began in the year 1835, when Juan Manuel de Rosas became president of the Argentine Confederation [...]. In 1836 the Colorados revolted against the Blanco-controlled government, which they overthrew two years later. The Blancos turned to President Rosas for support, which he willingly supplied. In 1839 the new Colorado-controlled government declared war on Argentina, starting a twelve-year conflict. Rosas not only enabled the Blancos to dominate the Uruguayan countryside but also encouraged them to give aid and asylum to the Farrapos rebels, across the frontier in Rio Grande do Sul." —Roderick J. Barman in Barman 1999, p. 125.

- ^ "quando o Brasil firmou-se como um país de governo sólido e situação interna estabilizada, a partir da vitória sobre a Farroupilha, em 1845, e contra a revolta pernambucana, consolidando, definitivamente, sua superioridade no continente. Compete admitir que, nesta mesma época, as novas repúblicas debatiam-se em lutas internas intermináveis iniciadas em 1810 e sofriam de visível complexo de insegurança em relação ao Brasil" —J. F. Maya Pedrosa in Pedrosa 2004, p. 35.

- ^ "The end of the Paraguayan War marked the apogee of the Imperial regime in Brazil. It is the 'Golden Age' of the monarchy." and "...Brazil had a reputation in the international community that, with the sole exception of the United States of America, no other country in the Americas held." —Heitor Lyra in Lyra 1977, Vol 2, p. 9.

<ref> ذو الاسم "Viscount of Mauá" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.Footnotes

- ^ أ ب Halperín Donghi 2007, p. 91.

- ^ أ ب ت Furtado 2000, p. 10.

- ^ أ ب ت Golin 2004, p. 42.

- ^ Calmon 2002, p. 196.

- ^ Costa 2003, p. 156.

- ^ أ ب Vainfas 2002, p. 447.

- ^ أ ب ت Holanda 1976, p. 113.

- ^ Vianna 1994, p. 528.

- ^ Estado-maior do Exército 1972, p. 546.

- ^ Maia 1975, p. 255.

- ^ أ ب Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 160.

- ^ Pedrosa 2004, p. 232.

- ^ أ ب Pedrosa 2004, p. 35.

- ^ Dolhnikoff 2005, p. 206.

- ^ Lima 1989, p. 159.

- ^ أ ب Golin 2004, p. 22.

- ^ Pedrosa 2004, p. 229.

- ^ Estado-maior do Exército 1972, p. 551.

- ^ Títara 1852, p. 161.

- ^ Estado-maior do Exército 1972, p. 554.

- ^ Magalhães 1978, p. 64.

- ^ Calmon 1975, p. 407.

- ^ Golin 2004, pp. 42, 43.

- ^ Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 164.

- ^ Calmon 2002, p. 195.

- ^ Shumway 1993, p. 173.

- ^ Adelman 2002, p. 257.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, p. 29.

- ^ Furtado 2000, p. 17.

- ^ Pedrosa 2004, p. 168.

- ^ Furtado 2000, p. 8.

- ^ أ ب Furtado 2000, p. 14.

References

- Adelman, Jeremy (2 July 2002). Republic of Capital: Buenos Aires and the Legal Transformation of the Atlantic World. Redwood City, Calif.: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-6414-8. OCLC 1041053757.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Barman, Roderick J. (1999). Citizen Emperor: Pedro II and the Making of Brazil, 1825–1891. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3510-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Barroso, Gustavo (2000). Guerra do Rosas: 1851–1852 (in Portuguese). Fortaleza: SECULT.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Bueno, Eduardo (2003). Brasil: Uma História (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Ática. ISBN 978-85-08-08213-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Calmon, Pedro (1975). História de D. Pedro II. 5 v (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: J. Olympio.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Calmon, Pedro (2002). História da Civilização Brasileira (in Portuguese). Brasília: Senado Federal.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Carvalho, Affonso (1976). Caxias (in Portuguese). Brasília: Biblioteca do Exército.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Costa, Virgílio Pereira da Silva (2003). Duque de Caxias (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Editora Três.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Dolhnikoff, Miriam (2005). Pacto imperial: origens do federalismo no Brasil do século XIX (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Globo. ISBN 978-85-250-4039-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Doratioto, Francisco (2002). Maldita Guerra: Nova história da Guerra do Paraguai (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. ISBN 978-85-359-0224-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Doratioto, Francisco (2009). Revista de História da Biblioteca Nacional (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: SABIN. 4 (41).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Estado-maior do Exército (1972). História do Exército Brasileiro: Perfil militar de um povo (in Portuguese). Vol. 2. Brasília: Instituto Nacional do Livro.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Furtado, Joaci Pereira (2000). A Guerra do Paraguai (1864–1870) (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Saraiva. ISBN 978-85-02-03102-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Golin, Tau (2004). A Fronteira (in Portuguese). Vol. 2. Porto Alegre: L&PM Editores. ISBN 978-85-254-1438-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Halperín Donghi, Tulio (2007). The Contemporary History of Latin America. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-1374-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Holanda, Sérgio Buarque de (1976). História Geral da Civilização Brasileira (II) (in Portuguese). Vol. 3. DIFEL/Difusão Editorial S.A.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Lewis, Daniel K. (2001). The history of Argentina. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-6254-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lima, Manuel de Oliveira (1989). O Império brasileiro (in Portuguese). Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia. ISBN 978-85-319-0517-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Lynch, John (2001). Argentine caudillo: Juan Manuel de Rosas. Lanham: SR Books. ISBN 978-0-8420-2898-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lyra, Heitor (1977). História de Dom Pedro II (1825–1891): Ascenção (1825–1870) (in Portuguese). Vol. 1. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Lyra, Heitor (1977). História de Dom Pedro II (1825–1891): Fastígio (1870–1880) (in Portuguese). Vol. 2. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Magalhães, João Batista (1978). Osório : síntese de seu perfil histórico (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Biblioteca do Exército.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Maia, João do Prado (1975). A Marinha de Guerra do Brasil na Colônia e no Império (in Portuguese) (2nd ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Livraria Editora Cátedra.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Palmerlee, Danny (2008). Argentina (6th ed.). Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74104-702-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pedrosa, J. F. Maya (2004). A Catástrofe dos Erros (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Biblioteca do Exército. ISBN 978-85-7011-352-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Scheina, Robert L. (2003). Latin America's Wars: The age of the caudillo, 1791–1899. Dulles: Brassey's. ISBN 978-1-57488-450-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shumway, Nicolas (18 March 1993). The Invention of Argentina. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08284-7. OCLC 891208597.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Títara, Ladislau dos Santos (1852). Memórias do grande exército alliado libertador do Sul da América (in Portuguese). Rio Grande do Sul: Tipografia de B. Berlink.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Vainfas, Ronaldo (2002). Dicionário do Brasil Imperial (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva. ISBN 978-85-7302-441-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Vianna, Hélio (1994). História do Brasil: período colonial, monarquia e república (in Portuguese) (15th ed.). São Paulo: Melhoramentos.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)