آيپاك

| |

| تأسست | 3 يناير 1963 |

|---|---|

| 53-0217164[2] | |

| الوضع القانوني | 501(c)(4) organization |

| المقر الرئيسي | Washington, D.C., United States[2] |

| الإحداثيات | 38°54′02″N 77°00′53″W / 38.9004676°N 77.0146576°W |

| Mort Fridman[2] | |

| Lillian Pinkus[2] | |

| Howard Kohr[2] | |

| المنظمات الفرعية | 251 Massachusetts Avenue LLC, American Israel Educational Foundation, AIPAC-AIEF Israel RA[2] |

الدخل (2014) | $77,709,827[2] |

| المصاريف (2014) | $69,267,598[2] (2014) |

| الوقف | $258,533[2] |

الموظفون (2013) | 396[2] |

المتطوعون (2013) | 60[2] |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www |

| تأسست | 1990 |

|---|---|

| 52-1623781 | |

| الوضع القانوني | 501(c)(3) organization |

الدخل (2014) | $55,234,555 |

| المصاريف (2014) | $50,266,476 (2014) |

| الوقف | $24,527,692 |

الموظفون (2013) | 0 |

المتطوعون (2013) | 39 |

لجنة الشؤون العامة الأمريكية الإسرائيلية تسمى اختصاراً أيپاك بالإنجليزية : American Israel Public Affairs Committee

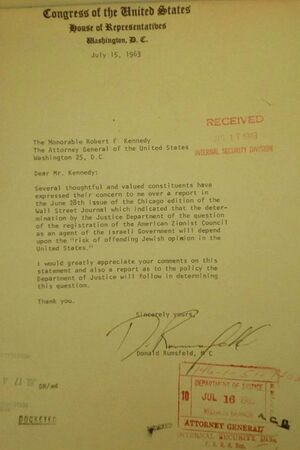

وهي أقوى جمعيات الضغط على أعضاء الكونگرس الأمريكي. هدفها تحقيق الدعم الأمريكي للكيان الصهيوني الموجود على أرض فلسطين. لا تقتصر الأيباك على اليهود بل يوجد بها أعضاء ديموقراطيين وجمهوريين. تم تأسيسها في عهد إدارة الرئيس الأمريكي دوايت أيزنهاور. تعتبر منظمة الأيباك منظمة صهيونية وقد يكون أكبر دليل على ذلك الاسم السابق لها والذي تأسست باسمه وهو American Zionist Committee for Public Affairs اللجنة الصهيونية الأمريكية للشؤون العامة والتي تم تأسيسها في سنة 1953. تم تحويل مسماها إلى ما هو معروف اليوم بالأيباك بعد تدهور علاقة داعمي إسرائيل والرئيس الأمريكي دوايت أيزنهاور حيث وصلت الأمور إلى إجراء تحقيقات مع اللجنة الصهيونية الأمريكية للشؤون العامة. لهذا تم تغيير الاسم و تأسست جماغة ضفط جديدة تُسمى اللجنة الإسرائيلية الأميركية للشؤون العامة.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

History

Formation (1953-1970s)

Journalist and lawyer Isaiah L. Kenen founded the American Zionist Committee for Public Affairs (AZCPA) as a lobbying division of the American Zionist Council (AZC), and they split in 1954.[3] Kenen, a lobbyist for the Israeli government,[4] had at earlier times worked for the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs. As a lobbyist, Kenen diverged from AZC's usual public relations efforts by trying to broaden support for Israel among traditionally non-Zionist groups. The founding of the new organization was in part a response to the negative international reaction to the October 1953 Qibya massacre, in which Israeli troops under Ariel Sharon killed at least sixty-nine Palestinian villagers, two-thirds of them women and children.[3] As the Eisenhower administration suspected the AZC of being funded by the government of Israel, it was decided that the lobbying efforts should be separated into a separate organization with separate finances.[3]

In 1959, AZCPA was renamed the American-Israel Public Affairs Committee, reflecting a broader membership and mission.[5][6] Kenen led the organization until his retirement in 1974, when he was succeeded by Morris J. Amitay.[7] According to commentator M.J. Rosenberg, Kenen was "an old-fashioned liberal," who did not seek to win support by donating to campaigns or otherwise influencing elections, but was willing to "play with the hand that is dealt to us."[8]

Rise (1970s to 1980s)

By the 1970s, the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations and AIPAC had assumed overall responsibility for Israel-related lobbying within the Jewish communal landscape. The Conference of Presidents was responsible for speaking to the Executive Branch of the U.S. government, while AIPAC dealt mainly with the Legislative Branch. Although it had worked effectively behind the scenes since its founding in 1953, AIPAC only became a powerful organization in the 15 years after the Yom Kippur War in 1973.[6]

By the mid-70s, AIPAC had achieved the financial and political clout necessary to sway congressional opinion, according to historian Michael Oren.[9] During this period, AIPAC's budget soared from $300,000 in 1973 to over $7 million during its peak years of influence in the late 1980s. Whereas Kenen had come out of the Zionist movement, with early staff pulled from the longtime activists among the Jewish community, AIPAC had evolved into a prototypical Washington-based lobbying and consulting firm. Leaders and staffers were recruited from legislative staff and lobbyists with direct experience with the federal bureaucracy.[6] Confronted with opposition from both houses of Congress, United States President Gerald Ford rescinded his 'reassessment.'"[9] George Lenczowski notes a similar, mid-1970s timeframe for the rise of AIPAC power: "It [the Jimmy Carter presidency] also coincides with the militant emergence of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) as a major force in shaping American policy toward the Middle East."[10]

In 1980, Thomas Dine became the executive director of AIPAC, and developed its grassroots campaign. By the late 1980s, AIPAC's board of directors was "dominated" by four successful businessmen—Mayer (Bubba) Mitchell, Edward Levy, Robert Asher, and Larry Weinberg.[11]

AIPAC scored two major victories in the early 1980s that established its image among political candidates as an organization "not to be trifled with" and set the pace for "a staunchly pro-Israel" Congress over the next three decades.[12] In 1982, activists affiliated with AIPAC in Skokie, Illinois, backed Richard J. Durbin to oust U.S. Representative Paul Findley (R-Illinois), who had shown enthusiasm for PLO leader Yasir Arafat. In 1984, Senator Charles H. Percy (R-Illinois), then-chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and a supporter of a deal to allow Saudi Arabia to buy sophisticated Airborne early warning and control (AWAC) military planes was defeated by Democrat Paul Simon. Simon was asked by Robert Asher, an AIPAC board member in Chicago, to run against Percy.[12]

Contemporary period (Post-1980s)

In 2005, Lawrence Franklin, a Pentagon analyst pleaded guilty to espionage charges of passing U.S. government secrets to AIPAC policy director Steve J. Rosen and AIPAC senior Iran analyst Keith Weissman, in what is known as the AIPAC espionage scandal. Rosen and Weissman were later fired by AIPAC.[13] In 2009, charges against the former AIPAC employees were dropped.[14]

In February 2019, freshman U.S. Representative Ilhan Omar (D-Minnesota), one of the first two Muslim women (along with Rashida Tlaib) to serve in Congress, tweeted that House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy's (R-California) support for Israel was “all about the Benjamins” (i.e. about the money).[15] The next day, she clarified that she meant AIPAC.[16] Omar later apologized but also made another statement attacking "political influence in this country that says it is okay to push for allegiance to a foreign country.” The statements aroused anger among AIPAC supporters, but also vocal support among the progressive wing of the Democratic Party and "revived a fraught debate" in American politics over whether AIPAC has too much influence over American policy in the Middle East,[12] while highlighting the deterioration of some relationships between progressive Democrats and pro-Israel organizations.[16] On March 6, 2019, the Democratic leadership put forth a resolution on the House floor condemning anti-Semitism, which was broadened to condemn bigotry against a wide variety of groups before it passed on March 7.[17][18]

الأهداف والغايات

صرحت الأيباك بالأهداف التالية:

- الضغط على الفلسطينيين.

- تقوية العلاقات ما بين واشنطن وإسرائيل من خلال التعاون ما بين أجهزة مخابرات البلدين والمساعدات العسكرية والاقتصادية. (بلغت في سنة 2006 2.52 مليار دولار أمريكي.

- إدانة الإجراءات الإيرانية الساعية للحصول على التكنولوجيا النووية وموقفها المنكر للمحرقة.

- إجراءات إضافية على الدول والمجموعات المعادية لإسرائيل.

مؤتمر السياسات

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2016

In 2016, nearly 20,000 delegates attended the AIPAC Policy Conference; approximately 4,000 of those delegates were American students.[19] For the first time in AIPAC's history, the general sessions of Policy Conference were held in Washington, D.C.'s Verizon Center in order to accommodate the large number of delegates. Keynote speakers included Vice President Joe Biden, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump, Governor John Kasich, Senator Ted Cruz, and Speaker Paul Ryan. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who has spoken at AIPAC before in person, addressed Policy Conference via satellite on the final day of the conference. Senator Bernie Sanders chose not to attend the conference.[20]

حقائق

تم ربط الأيباك بعدد من الحوادث الخلافية مثل:

في سنة 1992 قام رئيس الأيباك ديڤد شتاينر بالاستقالة عندما تم إجراء تسجيل صوتي له يتباها فيه عن تأثيره السياسي في الحصول على المساعدات للكيان الإسرائيلي. مما يجدر ذكره بأن من قام بالتسجيل الصوتي هو يهودي يدعى حاييم كاتز حيث قال :"كيهودي، فإنه أمر يهمني في حالة وجود مجموعة صغيرة ذات قوة غير متنجانسة. أعتقد أن هذا يؤذي الجميع، ومن ضمنهم اليهود. إذا أراد ديفيد ستاينر أن يتكلم عن التأثير القوي للأيباك، فلا بد للعامة أن يعرفوا ما يقول".

أبرز الأعضاء والداعمين

قائمة الرؤساء

- Robert Asher, 1962–1964, a lighting-fixtures dealer in Chicago

- Edward Levy, Jr., 1964–1965, a building-supplies executive in Detroit

- Mayer "Bubba" Mitchell, 1965–1968, a scrap-metal dealer in Mobile, Alabama

- Larry Weinberg, 1968–1970, a real-estate broker in Los Angeles (and a former owner of the Portland Trail Blazers)

- David Steiner, 1970–1976, New Jersey real estate developer

- Steven Grossman, 1976–1976, communications executive and Democratic Party chairman

- Melvin Dow, 1976–1978, a Houston attorney

- Lonny Kaplan, 1978–1980, New Jersey insurance executive.

- Tim Wuliger, 1980–1981, Cleveland investor

- Bernice Manocherian, 1984–1986

- Amy Friedkin, 2004–2006, San Francisco, active in grassroots Jewish organisations.

- Howard Friedman, 2006–2008

مرئيات

| حسن نصر الله، يتحدث عن اللوبي الاسرائيلي بالولايات المتحدة، ويقول أن اسرائيل أداة أمريكية في المنطقة |

المراجع

- ^ "American Israel Public Affairs Committee[dead link]". Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs. Government of the District of Columbia. Accessed on March 24, 2016.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش "Form 990: Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax". American Israel Public Affairs Committee. Guidestar. September 30, 2014.

- ^ أ ب ت Rossinow, Doug (2018). ""The Edge of the Abyss": The Origins of the Israel Lobby, 1949–1954". Modern American History. Cambridge University Press (CUP). 1 (1): 23–43. doi:10.1017/mah.2017.17. ISSN 2515-0456.

This organization's original name had been the American Zionist Committee for Public Affairs (AZCPA), and it had begun operations in 1954.

- ^ "The pro-Israel groups planning to spend millions in US elections". The Guardian. 22 April 2024. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ Rossinow, Doug (2018). ""The Edge of the Abyss": The Origins of the Israel Lobby, 1949–1954". Modern American History (in الإنجليزية). 1 (1): 23–43. doi:10.1017/mah.2017.17. ISSN 2515-0456.

In 1959, the AZCPA was renamed AIPAC, 'Israel' replacing 'Zionist.' The new name acknowledged ostensibly non-Zionist participants in the committee….American Jews redefined Zionism to mean providing staunch and generally unquestioning support for the State of Israel, so long as the leaders of Jewish Israel maintained respect for the legitimacy and integrity of American Jewry as a Jewish community.

- ^ أ ب ت Wertheimer, Jack (1995). "Jewish Organizational Life in the United States Since 1945". The American Jewish Year Book. 95: 3–98.

- ^ Langer, Emily (February 13, 2023). "Morris Amitay, ardent advocate for Israel, dies at 86". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ Bruck, Connie (September 1, 2014). "Friends of Israel". The New Yorker. p. 53. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- ^ أ ب Michael Oren (2007). Power, Faith, and Fantasy: America in the Middle East 1776 to the Present (New York: W.W. Norton & Company) p. 536. "The infelicitous combination of Ford and Rabin produced the direst crisis in US-Israeli relations since Suez, with Ford pronouncing a "reassessment" of American support for the Jewish state. Rabin responded by mobilizing the American Israel Public Affairs Committee --- AIPAC, the pro-Israel lobby --- against the president. Though founded in 1953, AIPAC had only now in the mid-70s, achieved the financial and political clout necessary to sway congressional opinion. Confronted with opposition from both houses of Congress, Ford rescinded his 'reassessment'."

- ^ Lenczowski, George (1990). American Presidents and the Middle East. Duke University Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-8223-0972-7.

- ^ Bruck, Connie (September 1, 2014). "Friends of Israel". The New Yorker. pp. 53–4. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- ^ أ ب ت Stolberg, Sheryl Gay (4 March 2019). "Ilhan Omar's Criticism Raises the Question: Is Aipac Too Powerful?". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ "Guilty plea entered in Pentagon Spy Case". Ynetnews. Associated Press. June 10, 2005. Retrieved August 26, 2022.

- ^ Lewis, Neil A.; Johnston, David (May 2, 2009). "U.S. to Drop Spy Case Against Pro-Israel Lobbyists". The New York Times.

- ^ Bade, Rachael; Phillips, Kristine; DeBonis, Mike; Flynn, Meagan (11 February 2019). "Democratic leaders call Ilhan Omar's Israel tweets 'deeply offensive'". The Washington Post. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ أ ب Yglesias, Matthew (6 March 2019). "The controversy over Ilhan Omar and AIPAC money, explained". Vox. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Stolberg, Sheryl Gay (7 March 2019). "House Votes to Condemn All Hate as Anti-Semitism Debate Overshadows Congress". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Friedman, Thomas L. (6 March 2019). "Ilhan Omar, Aipac and Me". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Reznik, Ethan (April 27, 2016). "Special Report: AIPAC Policy Conference strengthens American-Israel alliance". Webb Canyon Chronicle. Vol. VIII. Retrieved August 7, 2016.[المصدر لا يؤكد ذلك]

- ^ Kopan, Tal (March 18, 2016). "Bernie Sanders will not attend AIPAC conference". CNN.

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

للاستزادة

- Kenen, Isaiah (1981). Israel's Defense Line: Her Friends and Foes in Washington. ISBN 0-87975-159-2

- Smith, Grant F. (2008). America's Defense Line: The Justice Department's Battle to Register the Israel Lobby as Agents of a Foreign Government. ISBN 0-9764437-2-4

- Mearsheimer, John J. and Walt, Stephen M. (2007). The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy. ISBN 0-374-17772-4

- Oren, Michael (2007). Power, Faith, and Fantasy: The United States in the Middle East, 1776 to 2006. ISBN 0-393-05826-3

- Petras, James (2006). The Power of Israel in the United States. ISBN 0-932863-51-5

وصلات خارجية

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Articles with dead external links from May 2019

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Coordinates not on Wikidata

- Pages using infobox organization with unknown parameters

- Pages with empty portal template

- 501(c)(4) nonprofit organizations

- American Israel Public Affairs Committee

- Foreign policy political advocacy groups in the United States

- Israel–United States relations

- Lobbying organizations in the United States

- Organizations based in Washington, D.C.

- منظمات تأسست في 1963

- Zionism in the United States

- منظمات صهيونية

- 1963 establishments in the United States