العصر الحجري الحديث قبل الفخار

The Fertile Crescent, ح. 7500 BCE (PPNB), with main Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites (black squares for pre-agricultural sites). The area of Mesopotamia proper was not yet settled by humans. | |

| النطاق الجغرافي | Fertile Crescent |

|---|---|

| الفترة | Neolithic |

| التواريخ | ح. 10000 – 6500 BCE[1] |

| الموقع النمطي | Jericho |

| سبقها | Epipalaeolithic Near East (Kebaran culture, Natufian culture) Khiamian |

| تلاها | Pottery Neolithic. Halaf culture, Neolithic Greece, Faiyum A culture |

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN) represents the early Neolithic in the Levantine and upper Mesopotamian region of the Fertile Crescent, dating to ح. 12,000 years ago, (10000 – 6500 BCE).[1][3][4][5] It succeeds the Natufian culture of the Epipalaeolithic Near East (also called Mesolithic), as the domestication of plants and animals was in its formative stages, having possibly been induced by the Younger Dryas.

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic culture came to an end around the time of the 8.2-kiloyear event, a cool spell centred on 6200 BCE that lasted several hundred years. It is succeeded by the Pottery Neolithic.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Chronology

قالب:Prehistoric Southwest Asia timeline

Pre-Pottery Neolithic A

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic is divided into Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA 10000–8800 BCE) and the following Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB 8800–6500 BCE).[1][5] These were originally defined by Kathleen Kenyon in the type site of Jericho (Palestine). The Pre-Pottery Neolithic precedes the ceramic Neolithic (Yarmukian culture, 6400 – 6200 BCE). At 'Ain Ghazal, in Jordan, the culture continued a few more centuries as the so-called Pre-Pottery Neolithic C culture.

Around 11000 years ago (9000 BCE), during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA), the "world's first town", Jericho, appeared in the Levant,[6] although the adequacy of this title has since been challenged.[7]

Sculpture of a predatory animal, Göbekli Tepe, circa 9000 BCE

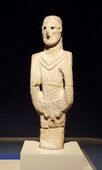

Urfa Man, ح. 9000 BCE. Şanlıurfa Archaeology and Mosaic Museum.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic is divided into Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (10000 – 8800 BCE) and the following Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (8800 – 6500 BCE).[1][5] PPNB differed from PPNA in showing greater use of domesticated animals, a different set of tools, and new architectural styles.

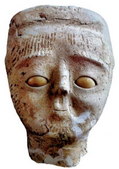

Head of a statue from Jericho, from c. 9000 years ago (7000 BCE). On display at the Rockefeller Museum, in Jerusalem.

Footed bowl in granite, Syria, end of 8th Millennium BCE.

Green aragonite tripod vase Mid-Euphrates 6000 BCE Louvre Museum AO 28386

Calcite tripod vase, mid-Euphrates, probably from Tell Buqras, 6000 BCE, Louvre Museum AO 31551

PPNB plastered skull from Tell Aswad, Syria, 7th Millennium BCE

Pre-Pottery Neolithic C

Work at the site of 'Ain Ghazal in Jordan has indicated a later Pre-Pottery Neolithic C period. Juris Zarins has proposed that a Circum Arabian Nomadic Pastoral Complex developed in the period from the climatic crisis of 6200 BCE, partly as a result of an increasing emphasis in PPNB cultures upon domesticated animals, and a fusion with Harifian hunter-gatherers in the Southern Levant, with affiliate connections with the cultures of Fayyum and the Eastern Desert of Egypt. Cultures practicing this lifestyle spread down the Red Sea shoreline and moved east from Syria into southern Iraq.[8]

In Israel, PPNC sites are rather rare.[9] By 2008, only four sites had been clearly identified: Ashkelon (Afridar) and 'Atlit Yam on the coast, stratum II at Tel 'Ali one mile south of the Sea of Galilee, and Ha-Gosherim in the north.[9]

ʿAin Ghazal statues: closeup of one of the bicephalous statues, ح. 6500 BCE.

Ain Ghazal statue on show in the Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Two-headed statue from the Jordan Museum

Diffusion

Europe

Carbon 14 dating

The spread of the Neolithic in Europe was first studied quantitatively in the 1970s, when a sufficient number of 14C age determinations for early Neolithic sites had become available.[10] Ammerman and Cavalli-Sforza discovered a linear relationship between the age of an Early Neolithic site and its distance from the conventional source in the Near East (Jericho), thus demonstrating that, on average, the Neolithic spread at a constant speed of about 1 km/yr.[10] More recent studies confirm these results and yield the speed of 0.6–1.3 km/yr at 95% confidence level.[10]

Analysis of mitochondrial DNA

Since the original human expansions out of Africa 200,000 years ago, different prehistoric and historic migration events have taken place in Europe.[11] Considering that the movement of the people implies a consequent movement of their genes, it is possible to estimate the impact of these migrations through the genetic analysis of human populations.[11] Agricultural and husbandry practices originated 10,000 years ago in a region of the Near East known as the Fertile Crescent.[11] According to the archaeological record this phenomenon, known as "Neolithic", rapidly expanded from these territories into Europe.[11] However, whether this diffusion was accompanied or not by human migrations is greatly debated.[11] Mitochondrial DNA –a type of maternally inherited DNA located in the cell cytoplasm- was recovered from the remains of Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) farmers in the Near East and then compared to available data from other Neolithic populations in Europe and also to modern populations from South-Eastern Europe and the Near East.[11] The obtained results show that substantial human migrations were involved in the Neolithic spread and suggest that the first Neolithic farmers entered Europe following a maritime route through Cyprus and the Aegean Islands.[11]

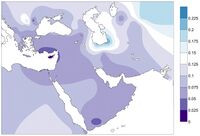

Ancient European Neolithic farmers are genetically closest to modern Near-Eastern/ Anatolian populations: genetic matrilineal distances between European Neolithic Linear Pottery culture populations (5,500–4,900 calibrated BC) and modern Western Eurasian populations.[12]

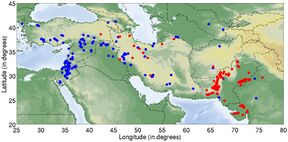

جنوب آسيا

The earliest Neolithic sites in South Asia are Bhirrana in Haryana, dated to 7570–6200 BCE,[14] and Mehrgarh, dated to between 6500 and 5500 BCE, in the Kachi plain of Baluchistan, Pakistan; the site has evidence of farming (wheat and barley) and herding (cattle, sheep and goats).

There is strong evidence for causal connections between the Near-Eastern Neolithic and that further east, up to the Indus Valley.[15] There are several lines of evidence that support the idea of a connection between the Neolithic in the Near East and in the Indian subcontinent.[15] The prehistoric site of Mehrgarh in Baluchistan (modern Pakistan) is the earliest Neolithic site in the north-west Indian subcontinent, dated as early as 8500 BCE.[15] Neolithic domesticated crops in Mehrgarh include more than barley and a small amount of wheat. There is good evidence for the local domestication of barley and the zebu cattle at Mehrgarh, but the wheat varieties are suggested to be of Near-Eastern origin, as the modern distribution of wild varieties of wheat is limited to Northern Levant and Southern Turkey.[15] A detailed satellite map study of a few archaeological sites in the Baluchistan and Khybar Pakhtunkhwa regions also suggests similarities in early phases of farming with sites in Western Asia.[15] Pottery prepared by sequential slab construction, circular fire pits filled with burnt pebbles, and large granaries are common to both Mehrgarh and many Mesopotamian sites.[15] The postures of the skeletal remains in graves at Mehrgarh bear a strong resemblance to those at Ali Kosh in the Zagros Mountains of southern Iran.[15] Despite their scarcity, the 14C and archaeological age determinations for early Neolithic sites in Southern Asia exhibit remarkable continuity across the vast region from the Near East to the Indian Subcontinent, consistent with a systematic eastward spread at a speed of about 0.65 km/yr.[15]

In South India, the Neolithic began by 6500 BCE and lasted until around 1400 BCE when the Megalithic transition period began. South Indian Neolithic is characterized by Ash mounds[مطلوب توضيح] from 2500 BCE in Karnataka region, expanded later to Tamil Nadu.[16]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Genetics

Lazaridis et al. (2022) stated that ancient Levantines (i.e. inhabitants of Jordan, Israel, Syria, Lebanon) and their descendants exhibit a decrease of ~8% local Neolithic ancestry, which is mostly Natufian ancestry, every millennium, starting from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic to the Medieval period. It was replaced by Caucasus-related and Anatolian-related ancestries, from the north and west respectively. However, despite the decline in the Natufian component, this key ancestry source made an important contribution to peoples of later periods, continuing until the present.[17]

Relative chronology

See also

References

- ^ أ ب ت ث Chazan, Michael (2017). World Prehistory and Archaeology: Pathways Through Time (in الإنجليزية). Routledge. p. 197. ISBN 978-1-351-80289-5.

- ^ Diamond, J.; Bellwood, P. (2003). "Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions". Science. 300 (5619): 597–603. Bibcode:2003Sci...300..597D. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1013.4523. doi:10.1126/science.1078208. PMID 12714734. S2CID 13350469.

- ^ Kuijt, I.; Finlayson, B. (Jun 2009). "Evidence for food storage and predomestication granaries 11,000 years ago in the Jordan Valley". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (27): 10966–10970. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10610966K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0812764106. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2700141. PMID 19549877.

- ^ Ozkaya, Vecihi (June 2009). "Körtik Tepe, a new Pre-Pottery Neolithic A site in south-eastern Anatolia". Antiquitey Journal, Volume 83, Issue 320.

- ^ أ ب ت Richard, Suzanne Near Eastern archaeology Eisenbrauns; illustrated edition (1 Aug 2004) ISBN 978-1-57506-083-5 p.244 [1]

- ^ Mithen, Steven (8 December 2011). After the Ice: A Global Human History, 20,000 - 5000 BC (in الإنجليزية). Orion. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-78022-259-2.

- ^ Liverani, Mario (11 July 2016). Imagining Babylon: The Modern Story of an Ancient City (in الإنجليزية). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 213. ISBN 978-1-61451-458-9.

- ^ Zarins, Juris (1992) "Pastoral Nomadism in Arabia: Ethnoarchaeology and the Archaeological Record", in Ofer Bar-Yosef and A. Khazanov, eds. "Pastoralism in the Levant"

- ^ أ ب Garfinkel, Yosef; Dag, Doron; Stager, Lawrence E. (2008). "Ashkelon: the Neolithic site in the Afridar neighborhood". The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land (NEAEHL). Israel Exploration Society, Biblical Archaeology Society.

- ^ أ ب ت Original text from Shukurov, Anvar; Sarson, Graeme R.; Gangal, Kavita (2014). "The Near-Eastern Roots of the Neolithic in South Asia". PLOS ONE (in الإنجليزية). 9 (5): e95714. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...995714G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095714. PMC 4012948. PMID 24806472.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Turbón, Daniel; Arroyo-Pardo, Eduardo (5 June 2014). "Ancient DNA Analysis of 8000 B.C. Near Eastern Farmers Supports an Early Neolithic Pioneer Maritime Colonization of Mainland Europe through Cyprus and the Aegean Islands". PLOS Genetics (in الإنجليزية). 10 (6): e1004401. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004401. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 4046922. PMID 24901650.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Turbón, Daniel; Arroyo-Pardo, Eduardo (5 June 2014). "Ancient DNA Analysis of 8000 B.C. Near Eastern Farmers Supports an Early Neolithic Pioneer Maritime Colonization of Mainland Europe through Cyprus and the Aegean Islands". PLOS Genetics (in الإنجليزية). 10 (6): e1004401. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004401. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 4046922. PMID 24901650.

- ^ Cooper, Alan (9 November 2010). "Ancient DNA from European Early Neolithic Farmers Reveals Their Near Eastern Affinities". PLOS Biology (in الإنجليزية). 8 (11): e1000536. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000536. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 2976717. PMID 21085689.

- ^ Shukurov, Anvar; Sarson, Graeme R.; Gangal, Kavita (7 May 2014). "The Near-Eastern Roots of the Neolithic in South Asia". PLOS ONE (in الإنجليزية). 9 (5): e95714. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...995714G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095714. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4012948. PMID 24806472.

- ^ Coningham, Robin; Young, Ruth (2015). The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c.6500 BCE–200 CE. Cambridge University Press Cambridge World Archeology. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-316-41898-7.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Shukurov, Anvar; Sarson, Graeme R.; Gangal, Kavita (7 May 2014). "The Near-Eastern Roots of the Neolithic in South Asia". PLOS ONE (in الإنجليزية). 9 (5): e95714. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...995714G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095714. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4012948. PMID 24806472.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Shukurov, Anvar; Sarson, Graeme R.; Gangal, Kavita (7 May 2014). "The Near-Eastern Roots of the Neolithic in South Asia". PLOS ONE (in الإنجليزية). 9 (5): e95714. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...995714G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095714. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4012948. PMID 24806472.

- ^ Asouti, Eleni; Fuller, Dorian Q (2007). قالب:Title case.

- ^ Lazaridis, Iosif; Alpaslan-Roodenberg, Songül; Acar, Ayşe; et al. (2022). "Ancient DNA from Mesopotamia suggests distinct Pre-Pottery and Pottery Neolithic migrations into Anatolia". Science. 377 (6609): 982–987. Bibcode:2022Sci...377..982L. doi:10.1126/science.abq0762. PMC 9983685. PMID 36007054.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Further reading

- J. Cauvin, Naissance des divinités, Naissance de l’agriculture. La révolution des symboles au Néolithique (CNRS 1994). Translation (T. Watkins) The birth of the gods and the origins of agriculture (Cambridge 2000).

- Ofer Bar-Yosef, The PPNA in the Levant – an overview. Paléorient 15/1, 1989, 57–63.

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تنظيف

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from February 2019

- Pre-Pottery Neolithic

- Neolithic cultures of Asia

- Archaeological cultures of the Near East

- Younger Dryas

![Ancient European Neolithic farmers are genetically closest to modern Near-Eastern/ Anatolian populations: genetic matrilineal distances between European Neolithic Linear Pottery culture populations (5,500–4,900 calibrated BC) and modern Western Eurasian populations.[12]](/w/images/thumb/1/19/Genetic_matrilineal_distances_between_European_Neolithic_Linear_Pottery_Culture_populations_%285%2C500%E2%80%934%2C900_calibrated_BC%29_and_modern_Western_Eurasian_populations.jpg/199px-Genetic_matrilineal_distances_between_European_Neolithic_Linear_Pottery_Culture_populations_%285%2C500%E2%80%934%2C900_calibrated_BC%29_and_modern_Western_Eurasian_populations.jpg)