احتشاء قلبي

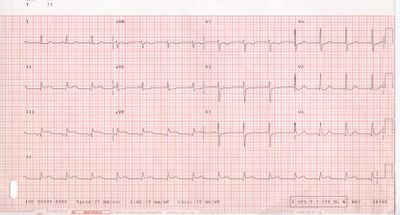

| مخطط احتشاء قلبي (2) في طرف الجدار الأمامي للقلب (an apical infarct) after occlusion (1) لفرع من الشريان التاجي الأيسر = LCA (, الشريان التاجي الايمن = RCA). | |

| ICD-10 | I21.-I22. |

| ICD-9 | 410 |

| DiseasesDB | 8664 |

| MedlinePlus | 000195 |

| eMedicine | med/1567 emerg/327 ped/2520 |

| MeSH | D009203 |

احتشاء العضلة القلبية ، يعرف أيضا باسم جلطة قلبية هو مرض قلبي حاد مهدد للحياة يحدث بسبب احتباس دموي نتيجة انسداد أحد الشرايين التاجية مما يؤدي إلى ضرر أو موت كامن لجزء من عضلة القلب. وغالبا ما تكون النوبة طارئا طبيا يهدد حياة المصاب ويستدعي الرعاية الفورية. وتُشَخص الحالة بواسطة تاريخ المريض الطبي ونتائج فحص تخطيط القلب و خمائر القلب في الدم.وأكثر الإجراآت إلحاحا هو إعادة تدفق الدم إلى القلب بأحد أمرين أو كليهما - إذابة الخثرة (وهي كدرة الدم المسببة لتسدد الشريان) بمساعدة الخمائر أو مضادات التخثر ، ورأب الوعاء (وتسمى أيضا توسعة الشرايين) وهو إيلاج وتد على متنه أنفوخة إلى الوعاء الدموي المتسدد، بحيث تنتفخ الأنفوخة حين تكون بمحاذاة الخثرة فتنحسر الخثرة نحو الجوانب فيتسع فضاء الوعاء بعدما ضاق، متيحا للدم الانسياب عبره. وينبغي على وحدة العناية التاجية مراقبة المريض عن كثب تحسبا لمختلف التطورات، وتقديم الوقاية الثانوية المتمثلة بإزالة العوامل التي قد تجر المزيد من النوبات.

Pathophysiology

Classification

By zone

Subendocardial vs. transmural

عوامل الخطر

عوامل خطر الداء القلبي الإكليلي (التاجي) هي عادة نفس عوامل خطر الاحتشاء القلبي:

الأعراض

يسبب احتشاء العضلة القلبية وهو ألم حاد في منتصف الصدر يوصف بأنه عاصر أو طاعن أو ضاغط أو ضيق شديد بالصدر وهو يماثل ألم الخناق الصدري ولكنه يتميز عنه ب

- يحدث بجهد أو بدون جهد

- شدته أكبر وقد يدوم لساعات

- لا يزول بالراحة ولا باعطاء النيترات

الألم يمتد عادة إلى الذراع الأيسر ولكنه قد يمتد إلى الرقبة والفك السفلي الكتف الذراع الأيمن الظهر أو الشرسوف يترافق مع أعراض التعرق الشديد البرودة الخفقان الغثيان الإقياء أو الشعور بالدوار

التشخيص

Electrocardiogram

The constellation of leads with ST segment elevation enables the clinician to identify what area of the heart is injured, which in turn helps predict the so-called culprit artery.

| Wall Affected | Leads Showing ST Segment Elevation | Leads Showing Reciprocal ST Segment Depression | Suspected Culprit Artery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Septal | V1, V2 | None | Left Anterior Descending (LAD) |

| Anterior | V3, V4 | None | Left Anterior Descending (LAD) |

| Anteroseptal | V1, V2, V3, V4 | None | Left Anterior Descending (LAD) |

| Anterolateral | V3, V4, V5, V6, I, aVL | II, III, aVF | Left Anterior Descending (LAD), Circumflex (LCX), or Obtuse Marginal |

| Extensive anterior (Sometimes called Anteroseptal with Lateral extension) | V1,V2,V3, V4, V5, V6, I, aVL | II, III, aVF | Left main coronary artery (LCA) |

| Inferior | II, III, aVF | I, aVL | Right Coronary Artery (RCA) or Circumflex (LCX) |

| Lateral | I, aVL, V5, V6 | II, III, aVF | Circumflex (LCX) or Obtuse Marginal |

| Posterior (Usually associated with Inferior or Lateral but can be isolated) | V7, V8, V9 | V1,V2,V3, V4 | Posterior Descending (PDA) (branch of the RCA or Circumflex (LCX)) |

| Right ventricular (Usually associated with Inferior) | II, III, aVF, V1, V4R | I, aVL | Right Coronary Artery (RCA) |

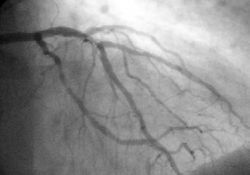

Angiography

Histopathology

First aid

As myocardial infarction is a common medical emergency, the signs are often part of first aid courses. The emergency action principles also apply in the case of myocardial infarction.

Immediate care

When symptoms of myocardial infarction occur, people wait an average of three hours, instead of doing what is recommended: calling for help immediately.[2][3] Acting immediately by calling the emergency services can prevent sustained damage to the heart ("time is muscle").[4]

Certain positions allow the patient to rest in a position which minimizes breathing difficulties. A half-sitting position with knees bent is often recommended. Access to more oxygen can be given by opening the window and widening the collar for easier breathing.

Aspirin can be given quickly (if the patient is not allergic to aspirin); but taking aspirin before calling the emergency medical services may be associated with unwanted delay.[5] Aspirin has an antiplatelet effect which inhibits formation of further thrombi (blood clots) that clog arteries. Non-enteric coated or soluble preparations are preferred. If chewed or dissolved, respectively, they can be absorbed by the body even quicker. If the patient cannot swallow, the aspirin can be used sublingually. U.S. guidelines recommend a dose of 162 – 325 mg.[6] Australian guidelines recommend a dose of 150 – 300 mg.[7]

Glyceryl trinitrate (nitroglycerin) sublingually (under the tongue) can be given if available.

If an Automated External Defibrillator (AED) is available the rescuer should immediately bring the AED to the patient's side and be prepared to follow its instructions, especially should the victim lose consciousness.

If possible the rescuer should obtain basic information from the victim, in case the patient is unable to answer questions once emergency medical technicians arrive. The victim's name and any information regarding the nature of the victim's pain will be useful to health care providers. The exact time that these symptoms started may be critical for determining what interventions can be safely attempted once the victim reaches the medical center. Other useful pieces of information include what the patient was doing at the onset of symptoms, and anything else that might give clues to the pathology of the chest pain. It is also very important to relay any actions that have been taken, such as the number or dose of aspirin or nitroglycerin given, to the EMS personnel.

Other general first aid principles include monitoring pulse, breathing, level of consciousness and, if possible, the blood pressure of the patient. In case of cardiac arrest, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) can be administered.

Automatic external defibrillation (AED)

Since the publication of data showing that the availability of automated external defibrillators (AEDs) in public places may significantly increase chances of survival, many of these have been installed in public buildings, public transport facilities, and in non-ambulance emergency vehicles (e.g. police cars and fire engines). AEDs analyze the heart's rhythm and determine whether the rhythm is amenable to defibrillation ("shockable"), as in ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation.

Emergency services

Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Systems vary considerably in their ability to evaluate and treat patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction. Some provide as little as first aid and early defibrillation. Others employ highly trained paramedics with sophisticated technology and advanced protocols.[8] Early access to EMS is promoted by a 9-1-1 system currently available to 90% of the population in the United States.[8] Most are capable of providing oxygen, IV access, sublingual nitroglycerine, morphine, and aspirin. Some are capable of providing thrombolytic therapy in the prehospital setting.[9][10]

With primary PCI emerging as the preferred therapy for ST segment elevation myocardial infarction, EMS can play a key role in reducing door to balloon intervals (the time from presentation to a hospital ER to the restoration of coronary artery blood flow) by performing a 12 lead ECG in the field and using this information to triage the patient to the most appropriate medical facility.[11][12][13][14] In addition, the 12 lead ECG can be transmitted to the receiving hospital, which enables time saving decisions to be made prior to the patient's arrival. This may include a "cardiac alert" or "STEMI alert" that calls in off duty personnel in areas where the cardiac cath lab is not staffed 24 hours a day.[15] Even in the absence of a formal alerting program, prehospital 12 lead ECGs are independently associated with reduced door to treatment intervals in the emergency department.[16]

Wilderness first aid

In wilderness first aid, a possible heart attack justifies evacuation by the fastest available means, including MEDEVAC, even in the earliest or precursor stages. The patient will rapidly be incapable of further exertion and have to be carried out.

Air travel

Certified personnel traveling by commercial aircraft may be able to assist an MI patient by using the on-board first aid kit, which may contain some cardiac drugs (such as glyceryl trinitrate spray, aspirin, or opioid painkillers), an AED,[17] and oxygen. Pilots may divert the flight to land at a nearby airport. Cardiac monitors are being introduced by some airlines, and they can be used by both on-board and ground-based physicians.[18]

العلاج

Percutaneous coronary intervention

Coronary artery bypass surgery

المضاعفات

Life-threatening arrhythmia

انظر أيضاً

- Acute coronary syndrome

- Angina

- Cardiac arrest

- Coronary thrombosis

- Hibernating myocardium

- Stunned myocardium

- Ventricular remodeling

المصادر

- ^ Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP. (2000). "Myocardial infarction redefined--a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction". J Am Coll Cardiol. 36 (3): 959–69. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00804-4. PMID 10987628.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Heart attack first aid. MedlinePlus. Retrieved December 3, 2006.

- ^ Act In Time to Heart Attack Signs - NHLBI. Retrieved December 13, 2006.

- ^ TIME IS MUSCLE TIME WASTED IS MUSCLE LOST. Early Heart Attack Care, St. Agnes Healthcare. Retrieved November 29, 2006.

- ^ Brown AL, Mann NC, Daya M, Goldberg R, Meischke H, Taylor J, Smith K, Osganian S, Cooper L. (2000). "Demographic, belief, and situational factors influencing the decision to utilize emergency medical services among chest pain patients. Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment (REACT) study". Circulation. 102 (2): 173–8. PMID 10889127.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, Bates ER, Green LA, Hand M, Hochman JS, Krumholz HM, Kushner FG, Lamas GA, Mullany CJ, Ornato JP, Pearle DL, Sloan MA, Smith SC Jr (2004). "ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction)". J Am Coll Cardiol. 44: 671–719. PMID 15358045.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006. ISBN 0-9757919-2-3.

- ^ أ ب Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW; et al. (2004). "ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction--executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to revise the 1999 guidelines for the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction)". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 44 (3): 671–719. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2004.07.002. PMID 15358045.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Morrow DA, Antman EM, Sayah A; et al. (2002). "Evaluation of the time saved by prehospital initiation of reteplase for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: results of The Early Retavase-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (ER-TIMI) 19 trial". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 40 (1): 71–7. PMID 12103258.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Morrison LJ, Verbeek PR, McDonald AC, Sawadsky BV, Cook DJ. (2000). "Mortality and prehospital thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction: A meta-analysis" (PDF). JAMA. 283 (20): 2686–92. doi:10.1001/jama.283.20.2686. PMID 10819952.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rokos IC, Larson DM, Henry TD; et al. (2006). "Rationale for establishing regional ST-elevation myocardial infarction receiving center (SRC) networks". Am. Heart J. 152 (4): 661–7. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2006.06.001. PMID 16996830.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Moyer P, Feldman J, Levine J; et al. (2004). "Implications of the Mechanical (PCI) vs Thrombolytic Controversy for ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction on the Organization of Emergency Medical Services: The Boston EMS Experience". Crit Pathw Cardiol. 3 (2): 53–61. doi:10.1097/01.hpc.0000128714.35330.6d. PMID 18340140.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Terkelsen CJ, Lassen JF, Nørgaard BL; et al. (2005). "Reduction of treatment delay in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: impact of pre-hospital diagnosis and direct referral to primary percutanous coronary intervention". Eur. Heart J. 26 (8): 770–7. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehi100. PMID 15684279.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)T - ^ Henry TD, Atkins JM, Cunningham MS; et al. (2006). "ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: recommendations on triage of patients to heart attack centers: is it time for a national policy for the treatment of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction?". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 47 (7): 1339–45. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.101. PMID 16580518.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rokos I. and Bouthillet T., "The emergency medical systems-to-balloon (E2B) challenge: building on the foundations of the D2B Alliance," STEMI Systems, Issue Two, May 2007. Accessed June 16, 2007.

- ^ Cannon, Christopher (1999). Management of acute coronary syndromes. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. ISBN 0-89603-552-2.

- ^ Youngwith, Janice (2008-02-06). "Saving hearts in the air". Dailyherald.com. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

- ^ Dowdall N. "'Is there a doctor on the aircraft?' Top 10 in-flight medical emergencies." BMJ 2000; 321(7272):1336-7. PMID 11090520. قالب:PMC

وصلات خارجية

- PROCAM Risk Calculator estimating your risk of a heart attack (myocardial infarction) within the next 10 years based on data of the PROCAM study, provided by the International Task Force for Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease

- Risk Assessment Tool for Estimating 10-year Risk of Having a Heart Attack - based on information of the Framingham Heart Study, from the United States National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute

- Heart Attack - overview of resources from MedlinePlus.

- American Heart Association's Heart Attack web site - Information and resources for preventing, recognizing and treating heart attack.

| هذه بذرة مقالة عن العلوم الطبية تحتاج للنمو والتحسين، فساهم في إثرائها بالمشاركة في تحريرها. |