إثلستان

| Æthelstan | |

|---|---|

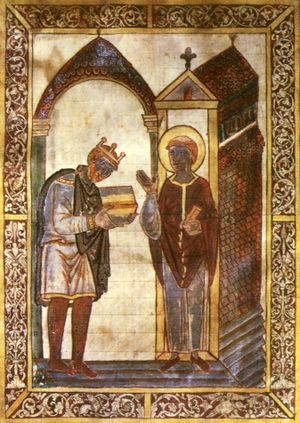

Æthelstan presenting a book to St Cuthbert, the earliest surviving portrait of an English king. Illustration in a manuscript of Bede's Life of Saint Cuthbert[1] presented by Æthelstan to the saint's shrine in Chester-le-Street. He wore a crown of the same design on his "crowned bust" coins.[2] | |

| King of the Anglo-Saxons | |

| العهد | 924–927 |

| التتويج | 4 September 925 |

| سبقه | Edward the Elder or Ælfweard |

| King of the English | |

| العهد | 927 – 27 October 939 |

| تبعه | Edmund I |

| وُلِد | ح. 894 Wessex |

| توفي | 27 October 939 (about 45) Gloucester, إنگلترة |

| الدفن | |

| البيت | Wessex |

| الأب | Edward the Elder |

| الأم | Ecgwynn |

Æthelstan or Athelstan ( /ˈæθəlstæn/; الإنگليزية القديمة: Æþelstan[أ] or Æðelstān;[ب] نورسية القديمة: Aðalsteinn meaning "noble stone"; ح. 894 – 27 October 939) was King of the Anglo-Saxons from 924 to 927 and King of the English from 927 to 939 when he died.[ت] He was the son of King Edward the Elder and his first wife, Ecgwynn. Modern historians regard him as the first King of England and one of the greatest Anglo-Saxon kings. He never married and had no children. He was succeeded by his half-brother, Edmund.

When Edward died in July 924, Æthelstan was accepted by the Mercians as king. His half-brother Ælfweard may have been recognised as king in Wessex, but died within three weeks of their father's death. Æthelstan encountered resistance in Wessex for several months, and was not crowned until September 925. In 927 he conquered the last remaining Viking kingdom, York, making him the first Anglo-Saxon ruler of the whole of England. In 934 he invaded Scotland and forced Constantine II to submit to him, but Æthelstan's rule was resented by the Scots and Vikings, and in 937 they invaded England. Æthelstan defeated them at the Battle of Brunanburh, a victory which gave him great prestige both in the British Isles and on the Continent. After his death in 939 the Vikings seized back control of York, and it was not finally reconquered until 954.

Æthelstan centralised government; he increased control over the production of charters and summoned leading figures from distant areas to his councils. These meetings were also attended by rulers from outside his territory, especially Welsh kings, who thus acknowledged his overlordship. More legal texts survive from his reign than from any other 10th-century English king. They show his concern about widespread robberies, and the threat they posed to social order. His legal reforms built on those of his grandfather, Alfred the Great. Æthelstan was one of the most pious West Saxon kings, and was known for collecting relics and founding churches. His household was the centre of English learning during his reign, and it laid the foundation for the Benedictine monastic reform later in the century. No other West Saxon king played as important a role in European politics as Æthelstan, and he arranged the marriages of several of his sisters to continental rulers.

خلفية

By the ninth century the many kingdoms of the early Anglo-Saxon period had been consolidated into four: Wessex, Mercia, Northumbria and East Anglia.[4] In the eighth century, Mercia had been the most powerful kingdom in southern England, but in the early ninth, Wessex became dominant under Æthelstan's great-great-grandfather, Egbert. In the middle of the century, England came under increasing attack from Viking raids, culminating in invasion by the Great Heathen Army in 865. By 878, the Vikings had overrun East Anglia, Northumbria, and Mercia, and nearly conquered Wessex. The West Saxons fought back under Alfred the Great, and achieved a decisive victory at the Battle of Edington.[5] Alfred and the Viking leader Guthrum agreed on a division that gave Alfred western Mercia, while eastern Mercia was incorporated into Viking East Anglia. In the 890s, renewed Viking attacks were successfully fought off by Alfred, assisted by his son (and Æthelstan's father) Edward and Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians. Æthelred ruled English Mercia under Alfred and was married to his daughter Æthelflæd. Alfred died in 899 and was succeeded by Edward. Æthelwold, the son of Æthelred, King Alfred's older brother and predecessor as king, made a bid for power, but was killed at the Battle of the Holme in 902.[6]

Early life

الحكم

النزاع على السلطة

ملك الإنگليز

Æthelstan became the first king of all the Anglo-Saxon peoples, and in effect overlord of Britain.[7][ث]

غزو اسكتلندة في 934

In 934 Æthelstan invaded Scotland. His reasons are unclear, and historians give alternative explanations. The death of his half-brother Edwin in 933 might have finally removed factions in Wessex opposed to his rule. Guthfrith, the Norse king of Dublin who had briefly ruled Northumbria, died in 934; any resulting insecurity among the Danes would have given Æthelstan an opportunity to stamp his authority on the north. An entry in the Annals of Clonmacnoise, recording the death in 934 of a ruler who was possibly Ealdred of Bamburgh, suggests another possible explanation. This points to a dispute between Æthelstan and Constantine over control of his territory. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle briefly recorded the expedition without explanation, but the twelfth-century chronicler John of Worcester stated that Constantine had broken his treaty with Æthelstan.[9]

The Battle of Brunanburh

In 934 Olaf Guthfrithson succeeded his father Guthfrith as the Norse King of Dublin. The alliance between the Norse and the Scots was cemented by the marriage of Olaf to Constantine's daughter. By August 937 Olaf had defeated his rivals for control of the Viking part of Ireland, and he promptly launched a bid for the former Norse kingdom of York.

ملكاً

الادارة

العملة

الكنيسة

التعليم

العاهل البريطاني

وفاته

Æthelstan died at Gloucester on 27 October 939. His grandfather Alfred, his father Edward, and his half-brother Ælfweard had been buried at Winchester, but Æthelstan chose not to honour the city associated with opposition to his rule. By his own wish he was buried at Malmesbury Abbey, where he had buried his cousins who died at Brunanburh. No other member of the West Saxon royal family was buried there, and according to William of Malmesbury, Æthelstan's choice reflected his devotion to the abbey and to the memory of its seventh-century abbot, Saint Aldhelm. William described Æthelstan as fair-haired "as I have seen for myself in his remains, beautifully intertwined with gold threads". His bones were lost during the Reformation, but he is commemorated by an empty fifteenth-century tomb.[10]

المصادر الرئيسية

Chronicle sources for the life of Æthelstan are limited, and the first biography, by Sarah Foot, was only published in 2011.[11] The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in Æthelstan's reign is principally devoted to military events, and it is largely silent apart from recording his most important victories.[12] An important source is the twelfth-century chronicle of William of Malmesbury, but historians are cautious about accepting his testimony, much of which cannot be verified from other sources. David Dumville goes so far as to dismiss William's account entirely, regarding him as a "treacherous witness" whose account is unfortunately influential.[13] However, Sarah Foot is inclined to accept Michael Wood's argument that William's chronicle draws on a lost life of Æthelstan. She cautions, however, that we have no means of discovering how far William "improved" on the original.[14]

ملاحظات

- ^ Pronounced [ˈæðeɫstɑn]

- ^ Pronounced [ˈæðeɫstɑːn]

- ^ 9th-century West Saxon kings before Alfred the Great are generally described by historians as kings of Wessex or of the West Saxons. In the 880s Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians, accepted West Saxon lordship, and Alfred then adopted a new title, king of the Anglo-Saxons, representing his conception of a new polity of all the English people who were not under Viking rule. This endured until 927, when Æthelstan conquered Viking York, and adopted the title rex anglorum (king of the English), in recognition of his rule over the whole of England. The term "Englalonde" (England) came into use in the late 10th or early 11th century.[3]

- ^ The situation in northern Northumbria, however, is unclear. In the view of Ann Williams, the submission of Ealdred of Bamburgh was probably nominal, and it is likely that he acknowledged Constantine as his lord, but Alex Woolf sees Ealdred as a semi-independent ruler acknowledging West Saxon authority, like Æthelred of Mercia a generation earlier.[8]

المراجع

- ^ "History by the Month: September and the Coronation of Æthelstan'". Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. 8 September 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ Foot, Æthelstan: The First King of England, pp. 155–156

- ^ Entries on ninth century West Saxons kings describe them as kings of Wessex in Lapidge, et al., ed., Blackwell Encyclopaedia; Keynes, "Rulers of the English", pp. 513–515; Higham and Ryan, Anglo-Saxon World, p. 8

- ^ Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, pp. 95, 236

- ^ Keynes & Lapidge, Alfred the Great, pp. 11–13, 16–23

- ^ Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, pp. 259–269, 321–322

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةFoot 2011 20 - ^ Williams, "Ealdred"; Woolf, From Pictland to Alba, p. 158

- ^ Foot, Æthelstan: The First King of England, pp. 164–165; Woolf, From Pictland to Alba, pp. 158–165

- ^ Foot, Æthelstan: The First King of England, pp. 25, 186–87, 243; Thacker, "Dynastic Monasteries and Family Cults", pp. 254–255

- ^ Cooper, review of Foot, Æthelstan

- ^ Dumville, Wessex and England, p. 167

- ^ Dumville, Wessex and England, pp. 146, 168

- ^ Foot, Æthelstan: The First King of England, pp. 251–258, discussing an unpublished essay by Michael Wood.

المصادر

- Abels, Richard (1998). Alfred the Great: War, Kingship and Culture in Anglo-Saxon England. Longman. ISBN 0-582-04047-7.

- Bailey, Maggie (2001). "Ælfwynn, Second Lady of the Mercians". Edward the Elder 899–924. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-21497-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Blair, John (2005). The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921117-3.

- Brett, Caroline (1991). "A Breton pilgrim in England in the reign of King Æthelstan". In Jondorf, Gillian; Dumville, D.N. (eds.). France and the British Isles in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. The Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-487-5.

- Brooke, Christopher (2001). The Saxon and Norman Kings. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-23131-8.

- Brooks, Nicholas (1984). The Early History of the Church of Canterbury. Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-7185-1182-4.

- Campbell, James (2000). The Anglo-Saxon State. Hambledon & London. ISBN 1-85285-176-7.

- Charles-Edwards, T. M. (2013). Wales and the Britons 350–1064. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821731-2.

- Cooper, Tracy-Anne (March 2013). "Æthelstan: The First King of England by Sarah Foot (review)". Journal of World History. 24 (1): 189–192. doi:10.1353/jwh.2013.0025.

- Costambeys, Marios (2004). "Æthelflæd [Ethelfleda] (d. 918), ruler of the Mercians". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8907. Retrieved 25 October 2013. (subscription or UK public library membership مطلوبة)

- Cubitt, Catherine; Costambeys, Marios (2004). "Oda [St Oda, Odo] (d. 958), archbishop of Canterbury". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20541. Retrieved 9 December 2013. (subscription or UK public library membership مطلوبة)

- Davies, John Reuben (2013). "Wales and West Britain". In Stafford, Pauline (ed.). A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland c. 500–c. 1100. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-42513-8.

- Dumville, David (1992). Wessex and England from Alfred to Edgar: Six Essays on Political, Cultural, and Ecclesiastical Revival. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-308-7.

- Foot, Sarah (2004). "Æthelstan (Athelstan) (893/4–939), king of England". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/833. Retrieved 9 June 2012.(subscription or UK public library membership مطلوبة)

- Foot, Sarah (2007). "Where English Becomes British: Rethinking Contexts for Brunanburh". In Barrow, Julia; Wareham, Andrew (eds.). Myth, Rulership, Church and Charters. Ashgate. pp. 127–144. ISBN 978-0-7546-5120-8.

- Foot, Sarah (2011). Æthelstan: The First King of England. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12535-1.

- Gretsch, Mechtild (1999). The Intellectual Foundations of the English Benedictine Reform. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-03052-6.

- Halloran, Kevin (September 2013). "Anlaf Guthfrithson at York: A Non-existent Kingship?". Northern History. University of Leeds. 50 (2): 180–185. doi:10.1179/0078172X13Z.00000000042.

- Hart, Cyril (1973). "Athelstan 'Half King' and his family". Anglo-Saxon England. Cambridge University Press. 2: 115–144. doi:10.1017/s0263675100000375. ISBN 0-521-20218-3.

- Hart, Cyril (2004). "Sihtric Cáech (Sigtryggr Cáech) (d. 927), king of York". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49273. Retrieved 4 October 2012. (subscription or UK public library membership مطلوبة)

- Higham, N. J. (1993). The Kingdom of Northumbria: AD 350–1100. Alan Sutton. ISBN 0-86299-730-5.

- Hill, Paul (2004). The Age of Athelstan: Britain's Forgotten History. Tempus Publishing. ISBN 0-7524-2566-8.

- Insley, Charles (2013). "Southumbria". In Stafford, Pauline (ed.). A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland c. 500-c. 1100. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-42513-8.

- John, Eric (1982). "The Age of Edgar". In Campbell, James (ed.). The Anglo-Saxons. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-014395-5.

- Karkov, Catherine E. (2004). The Ruler Portraits of Anglo-Saxon England. Boydell. ISBN 1-84383-059-0.

- Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael, eds. (1983). Alfred the Great: Asser's Life of King Alfred & Other Contemporary Sources. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-044409-4.

- Keynes, Simon (1985). "King Æthelstan's books". Learning and Literature in Anglo-Saxon England. Cambridge University Press. pp. 143–201. ISBN 0-521-25902-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Keynes, Simon (1990). "Royal government and the written word in late Anglo-Saxon England". In McKitterick, Rosamund (ed.). The Uses of Literacy in Early Medieval Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-34409-3.

- Keynes, Simon (1999). "England, c. 900–1016". In Reuter, Timothy (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. III. Cambridge University Press. pp. 456–484. ISBN 0-521-36447-7.

- Keynes, Simon (2001). "Edward, King of the Anglo-Saxons". Edward the Elder 899–924. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-21497-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Keynes, Simon (2001). "Rulers of the English, c. 450–1066". The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Keynes, Simon (2008). "Edgar rex admirabilis". In Scragg, Donald (ed.). Edgar King of the English: New Interpretations. The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-399-4.

- Lapidge, Michael (1993). Anglo-Latin Literature 900–1066. The Hambledon Press. ISBN 1-85285-012-4.

- Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald, eds. (2001). "The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England". The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Lapidge, Michael (2004). "Dunstan [St Dunstan] (d. 988), archbishop of Canterbury". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8288. Retrieved 7 December 2013. (subscription or UK public library membership مطلوبة)

- Livingston, Michael, ed. (2011). The Battle of Brunanburh: A Casebook. University of Exeter Press. ISBN 978-0-85989-862-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editorlink=ignored (|editor-link=suggested) (help) - Livingston, Michael (2011). "The Roads to Brunanburh". In Livingston, Michael (ed.). The Battle of Brunanburh: A Casebook. University of Exeter Press. pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-0-85989-862-1.

- Maclean, Simon (2013). "Britain, Ireland and Europe, c. 900–c. 1100". In Stafford, Pauline (ed.). A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland c. 500-c. 1100. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-42513-8.

- Maddicott, John (2010). The Origins of the English Parliament, 924–1327. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958550-2.

- Miller, Sean (2001). "Æthelstan". The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Miller, Sean (2004). "Edward [called Edward the Elder] (870s?–924), king of the Anglo-Saxons". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8514. Retrieved 28 April 2013. (subscription or UK public library membership مطلوبة)

- Molyneaux, George (2015). The Formation of the English Kingdom in the Tenth Century. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-871791-1.

- Nelson, Janet (1999). Rulers and Ruling Families in Early Medieval Europe. Ashgate. ISBN 0-86078-802-4.

- Nelson, Janet L. (1999). "Rulers and government". In Reuter, Timothy (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume III c. 900–c. 1024. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36447-7.

- Nelson, Janet (2008). "The First Use of the Second Anglo-Saxon Ordo". Myth, Rulership, Church and Charters. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-5120-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Ortenberg, Veronica (2010). "'The King from Overseas: Why did Æthelstan Matter in Tenth-Century Continental Affairs?". In Rollason, David; Leyser, Conrad; Williams, Hannah (eds.). England and the Continent in the Tenth Century: Studies in Honour of Wilhelm Levison (1876–1947). Brepols. ISBN 978-2-503-53208-0.

- Pratt, David (2010). "Written Law and the Communication of Authority in Tenth-Century England". In Rollason, David; Leyser, Conrad; Williams, Hannah (eds.). England and the Continent in the Tenth Century: Studies in Honour of Wilhelm Levison (1876–1947). Brepols. ISBN 978-2-503-53208-0.

- Roach, Levi (August 2013). "Law codes and legal norms in later Anglo-Saxon England". Historical Research. Institute of Historical Research. 86 (233): 465–486. doi:10.1111/1468-2281.12001.

- Roach, Levi (2016). Æthelred the Unready. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-22972-1.

- Ryan, Martin J. (2013). "Conquest, Reform and the Making of England". In Higham, Nicholas J.; Ryan, Martin J. (eds.). The Anglo-Saxon World. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12534-4.

- Scragg, Donald (2001). "Battle of Brunanburh". The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Sharp, Sheila (Autumn 1997). "England, Europe and the Celtic World: King Athelstan's Foreign Policy". Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester. 79 (3): 197–219. doi:10.7227/BJRL.79.3.15.

- Sharp, Sheila (2001). "The West Saxon Tradition of Dynastic Marriage". Edward the Elder 899–924. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-21497-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Smyth, Alfred P (1984). Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80–1000. Edward Arnold. ISBN 0-7131-6305-4.

- Smyth, Alfred P. (1987). Scandinavian York and Dublin. Irish Academic Press. ISBN 0-7165-2365-5.

- Stafford, Pauline (2001). "Ealdorman". The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Stenton, Frank (1971). Anglo-Saxon England (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280139-5.

- Thacker, Alan (2001). "Dynastic Monasteries and Family Cults". Edward the Elder 899–924. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-21497-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Williams, Ann (1991). "Ælfflæd queen d. after 920". In Williams, Ann; Smyth, Alfred P.; Kirby, D. P. (eds.). A Biographical Dictionary of Dark Age Britain. Seaby. ISBN 1-85264-047-2.

- Williams, Ann (1991). "Athelstan, king of Wessex 924-39". A Biographical Dictionary of Dark Age Britain. Seaby. ISBN 1-85264-047-2.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Williams, Ann (1991). "Ealdred of Bamburgh". A Biographical Dictionary of Dark Age Britain. Seaby. ISBN 1-85264-047-2.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Wood, Michael (1983). "The Making of King Aethelstan's Empire: An English Charlemagne?". In Wormald, Patrick; Bullough, Donald; Collins, Roger (eds.). Ideal and Reality in Frankish and Anglo-Saxon Society. Basil Blackwell. pp. 250–272. ISBN 0-631-12661-9.

- Wood, Michael (1999). In search of England. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-024733-5.

- Wood, Michael (2005). In Search of the Dark Ages. BBC Books. ISBN 978-0-563-53431-0.

- Wood, Michael (2007). "'Stand strong against the monsters': kingship and learning in the empire of king Æthelstan". In Wormald, Patrick; Nelson, Janet (eds.). Lay Intellectuals in the Carolingian World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83453-7.

- Wood, Michael (2010). "A Carolingian Scholar in the Court of King Æthelstan". In Rollason, David; Leyser, Conrad; Williams, Hannah (eds.). England and the Continent in the Tenth Century: Studies in Honour of Wilhelm Levison (1876–1947). Brepols. ISBN 978-2-503-53208-0.

- "Aethelstan: The First King of England". King Alfred and the Anglo Saxons. No. 3.

- Woodman, D. A. (December 2013). "'Æthelstan A' and the rhetoric of rule". Anglo-Saxon England. Cambridge University Press. 42.

- Woolf, Alex (2007). From Pictland to Alba: 789–1070. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1233-8.

- Woolf, Alex (2013). "Scotland". In Stafford, Pauline (ed.). A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland c. 500-c. 1100. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-42513-8.

- Wormald, Patrick (1999). The Making of English Law: King Alfred to the Twelfth Century. Vol. 1. Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-13496-4.

- Wormald, Patrick (2004). "Æthelweard [Ethelwerd] (d. 998?)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8918. Retrieved 5 May 2013. (subscription or UK public library membership مطلوبة)

- Yorke, Barbara (1997). Bishop Æthelwold: His Career and Influence. The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-705-4.

- Yorke, Barbara (2001). "Edward as Ætheling". Edward the Elder 899–924. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-21497-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Yorke, Barbara (2004). "Æthelwold (St Æthelwold, Ethelwold) (904x9–984)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8920. Retrieved 5 March 2013. (subscription or UK public library membership مطلوبة)

- Zacher, Samantha (2011). "Multilingualism at the Court of King Æthelstan: Latin Praise Poetry and The Battle of Brunanburh". In Tyler, Elizabeth M. (ed.). Conceptualizing Multilingualism in England, c. 800-C. 1250. Brepols. ISBN 978-2-503-52856-4.

Further reading

- Holland, Tom (2016). Athelstan: The Making of England. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-241-18781-4.

وصلات خارجية

- قالب:PASE

- Athelstan on In Our Time at the BBC. (listen now)

- "Athelstan". Foot, Sarah. The Essay: Anglo-Saxon Portraits. BBC. Radio 3.

- Sillito, David (27 August 2009). "Viking hoard reveals its story". BBC Radio 4, Today Programme. (On The Vale of York Hoard)

إثلستان وُلِد: c. 893/895 توفي: 27 October 939

| ||

| ألقاب ملكية | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه Edward the Elder or Ælfweard |

King of the Anglo-Saxons 924–927 |

Conquest of York |

| لقب حديث | King of the English 927 – 27 October 939 |

تبعه Edmund I |

قالب:Monarchs of Wessex قالب:Mercian monarchs قالب:Northumbrian monarchs قالب:Viking Invasion of England

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- مقالات مميزة

- Articles containing إنگليزية القديمة (ح. 450-1100)-language text

- Articles containing نورسية القديمة-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Anglo-Saxon monarchs

- مواليد عقد 890

- وفيات 939

- 9th-century English people

- 10th-century English monarchs

- Christian monarchs

- Anglo-Saxon warriors

- ملوك مؤسسون

- House of Wessex

- West Saxon monarchs

- Mercian monarchs

- Northumbrian monarchs

- Monarchs of England before 1066

- Malmesbury Abbey