إستاكالكو

Iztacalco | |

|---|---|

|

Top: Ignacio Zaragoza Avenue; Middle: San Matías Monastery, Iztacalco Borough Hall; Bottom: San Matías main plaza; Palacio de los Deportes | |

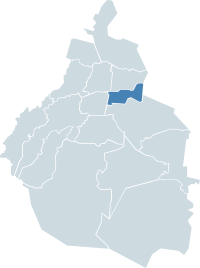

Iztacalco within Mexico City | |

| الإحداثيات: 19°23′43″N 99°05′52″W / 19.39528°N 99.09778°W | |

| Country | Mexico |

| Federal entity | Mexico City |

| Established | 1928 |

| السمِيْ | Pre-Columbian city |

| المقر | Río Churubusco y Avenida Té. Col. Ramos Millán, Iztacalco |

| الحكومة | |

| • Mayor | Raúl Armando Quintero Martínez (MORENA) |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 23٫21 كم² (8٫96 ميل²) |

| المنسوب | 2٬242 m (7٬356 ft) |

| التعداد (2020).[1] | |

| • الإجمالي | 404٬695 |

| • الكثافة | 17٬000/km2 (45٬000/sq mi) |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC-6 (Central Standard Time) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC-5 (Central Daylight Time) |

| Postal codes | 08000 – 08930 |

| مفتاح الهاتف | 55 |

| HDI (2020) | ▲ 0.835 Very High [2] |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | [1] |

Iztacalco (النطق الإسپاني: [istaˈkalko]) is a borough (demarcación territorial) in Mexico City. It is located in the central-eastern area and it is the smallest of the city's boroughs. The area's history began in 1309 when the island of Iztacalco, in what was Lake Texcoco, was settled in 1309 by the Mexica who would later found Tenochtitlan, according to the Codex Xolotl. The island community would remain small and isolated through the colonial period, but drainage projects in the Valley of Mexico dried up the lake around it. The area was transformed into a maze of small communities, artificial islands called chinampas and solid farmland divided by canals up until the first half of the 20th century. Politically, the area has been reorganized several times, being first incorporated in 1862 and the modern borough coming into existence in 1929. Today, all of the canals and farmland are dried out and urbanized as the most densely populated borough and the second most industrialized.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The borough

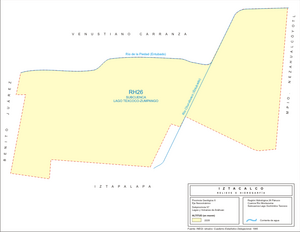

The borough of Iztacalco is located in the east-center of Mexico City bordering Venustiano Carranza, Iztapalapa and Benito Juárez boroughs, as well as the Mexico State municipality of Nezahualcoyotl .[3] It is the smallest of the city's boroughs.[4] The territory is divided into thirty eight neighborhoods called “colonias” or “barrios” along with 220 major apartment complexes.[5] The borough hall is located on Avenida Rio Churubusco in the Ramos Millán neighborhood.[3]

Seventy-one percent of the borough is occupied by residences, commerce, and service establishments.[4] Fifty-four percent of the territory is purely residential, down from 61% in 1980.%.[5] There are 99,577 housing units, almost all of which are constructed of cinderblock and concrete. The average housing unit has 4.1 occupants.[6][5] Many of these constructions are in some state of deterioration, which includes sixty percent of major housing complexes, as well as sixty percent of a type of housing situation, called a “vecindad.” Mixed-use zones, with residences, offices, services, and certain industries, have increased from 8.6% to 17%. Eleven percent is dedicated to manufacturing. Ninety percent of the land is paved over with only about two percent considered to be green space. Over 97% have basic services such as gas, electricity, garbage, and drainage.[5]

The Magdalena Mixhuca Sports City is located on Avenida Río Piedad in Colonia Magdalena Mixhuca. It contains boasts professional-level playing fields, swimming pools, running tracks and gyms.[6][3] The Palacio de los Deportes, also called the Domo de Cobre (“the Copper Dome”) is located on Avenida Río Churubusco and Viaducto Miguel Alemán in Colonia Granjas México. Connected to the complex is the Escuela Nacional de Entrenadores Deportivos and the Escuela Superior de Educación Física. As a private concert venue, it has hosted such acts as Aerosmith, Robbie Williams, The Cure and Shakira.[6][3]

The Autodromo Hermanos Rodríguez, with adjoining Foro Sol is located on Avenida Viaducto Piedad in Colonia Magdalena Mixhuca. The Foro Sol has also hosted major concerts.[6][3]

The La Viga Lienzo Charro (rodeo ring) is located on Guadalupe Street in Colonia Pantitlán.[6]

The main annual festival in the borough is the anniversary of the parish of San Matias in August, celebrating its establishment as the Franciscan monastery. It features the “charros of Iztacalco” who are based at the Lienzo Charro de la Viga, a tradition from the 19th century. Other important days include the festival dedicated to Saint Sebastian in January in the Barrio de Zapotla, Carnival in some neighborhoods, the Procession of the Holy Burial on Good Friday and a pre-Hispanic festival called Ue-izkal-ilhuitl, or the spring equinox .[6] The borough also hosts an annual youth event called the Festival Juventud. In 2011, this event included two days of rock and ska music at the Faro Iztacalco. It included bands such as Skandalo, Maskatesta and Los Korukos .[7]

Historic center

Although the borough is completely urbanized, there are still traces of the area's rural past, especially in the historic center, which corresponds to the original island in the former Lake Texcoco.[8][6] This zone is still divided into six neighborhoods called barrios: Santa Cruz, La Asunción, San Miguel, Los Reyes, Zapotla, San Francisco Xicaltongo y Santiago, along with an area called Santa Anita Zacatlalmanco Huéhuetl. Most of these lie along the Calzada de la Viga.[6] This area was designated as a "Barrio Mágico" by the city in 2011.[9]

The Barrio de Santa Cruz contains some of the oldest structures of the entire borough. One of these is the Capilla de Santa Cruz, located on a small street called Amador Aztlán. It has a Salomonic main portal with vegetative designs. It is only one level topped with a vaulted niche. Inside, there is a silver leaf main altar with a notable wood cross covered in silver and decorated with the image of the Passion of Christ and the date of 1748. The chapel was declared a historic monument in 1972. The Ermita de la Cruz is on Calle Agricultures. It was constructed by the Franciscans in the early 16th century and listed as a historic monument in 1955. The interior contains a crucified Christ done in pea cane paste. It also has an oil painting of the Virgin of Guadalupe. This barrio also contains a number of houses and other structures from the 18th and 19th centuries.[9]

However, the Barrio de la Asunción next door is home to the most important plaza and the church of the borough. The plaza is called either Plaza Miguel Hidalgo or Plaza San Matias, located between the parish of San Matías and Calzada de la Viga. It is of two levels with a number of trees and has a traditional kiosk in the center. It also has two important monuments, one of the Aztec glyph still used to designate the area and one of a bust of Miguel Hidalgo from 1870. The parish and former monastery of San Matías were begun in the 16th century. The main portal contains the main entrance, which consists of a richly decorated arch and two columns. Above it is an eight-sided choir window, and above that is a pediment in the form of a truncated triangle. Above this is a crest. There is one bell tower is Baroque. To the left of the facade, there is a dome over a chapel area, which is decorated with human figures and other elements. The interior contains chandeliers, arches and the main altar that features a marine shell.[9] Saint Matthew continues to be the patron saint of the Iztacalco.[10]

The Barrio de Santiago is marked by the Santiago Apóstol Church from the 18th century. It has a façade nearly without curves and almost square, covered in tezontle stone. On each side of the facade, there is a slim bell tower. The main entrance is marked by a simple arch of sandstone which contains a seashell and supported by two pilasters. Above this entrance, there is a clock. The interior is bright due to the many stained glass windows.[9]

Geography

The borough extends over 23.1 km2 or 2,317.4 hectares, all of which is urbanized. It accounts for 1.75% of the total territory of Mexico City, and it is the smallest of the 16 boroughs.[6][4] The land is flat and located on the lakebed of Lake Texcoco in the Valley of Mexico at an altitude of 2,235 meters above sea level. Today, however, the lake in this area has dried completely and the canals, wetlands and lake of the territory have completely disappeared.[8][6] The climate is considered to be semi-arid and temperate, with only the area bordering Benito Juárez and Iztapalapa considered to be semi-moist with rains in the summer. Overall, the borough is the driest in Mexico City, with an annual rainfall of not over 600 to 700mm per year. With over 90% paved over, there are no wild habitats left in the borough. Of the 2.34% dedicated to green space, most of these are traffic islands on major thoroughfares.[6]

There are only two parks in the borough. The Urbano-Ecológico School-Park is located on Calzada Ignacio Zaragoza in Colonia Agrícola Oriental, near the border of Iztapalapa. This park has less than one hectare. The other large green space is the parkland around the Magdalena Mixhuca Sports Center, which has been reforested with eucalyptus trees.[6]

Demographics

Iztacalco is the most densely populated borough in Mexico City and the most dense subdivision in the country.[8][10] As of 2020, the population was 404,695, with most being from the lower middle to lower classes.[6][4] There are small communities of middle-class families in Reforma Iztaccihuatl, Militar Marte and Viaducto Piedad.[6][5] Despite its density, the overall population of the borough has been dropping between one and two percent since 1990, but still about twenty percent of the current population moved into here from elsewhere in Mexico. The population is expected to continue decreasing.[4][5]

About 5,400 people who speak an indigenous language, with thirty eight different indigenous ethnicities present. About 1,100 of these speak some form of Nahuatl, followed by Zapotec, Mixtec, Otomi, Mazateca, Mazahua and Totonaca. About 91% of the population is Catholic, with about seven percent belonging to Protestant or Evangelical churches.[5]

History

While the most accepted interpretation of Iztacalco (from Nahuatl) is “house of salt,” others have been proposed such as “place of white houses.” Originally, the name was written “Ixtacalco” but its current spelling was adopted in the second half of the 20th century.[6] The crest or seal of the borough is the Aztec glyph which has been used to designate the place since at least the time of the Mendocino Codex, which depicts the “house” and “salt” interpretations of the name.[11] It contains a sun shining over a house. Inside the house, there is a grain of salt and two markings that represent raindrops’ tracks.[3]

Because it was originally an island well within Lake Texcoco, Iztacalco was settled by humans later than the rest of the Valley of Mexico .[6] The history of Iztacalco begins in 1309.[11] The Xolotl Codex states that Iztacalco was one of the people's last stops before they finally settled Tenochtitlan. The island was conquered and subject to the dominion of Texcoco as part of the territory of the Triple Alliance. From the beginning, inhabitants made a living by extracting salt from the brackish waters of the surrounding lake. This salt was consumed until the very early 20th century.[6][11]

Just after the Conquest, the area belonged to a territory called San Juan de Dios ruled directly from Mexico City.[9] A small monastery dedicated to Saint Matthew was constructed in which lived no more than two monks, with no more than 300 indigenous. As the area was very sparsely populated, these monks did not establish satellite parishes, except for the San Antonio hermitage, built for the feast day of this saint. In the middle of the 17th century, baptisms began to be recorded in the area, which then consisted of the main community and eight surrounding neighborhoods called barrios.[5][11] Through the colonial period, Iztacalco was on an island, which impeded its growth. It had only 296 residents in its barrios of Asunción, Santa Cruz, Santiago, San Miguel and Los Reyes.[11]

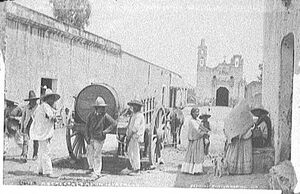

From the colonial period to the 19th century, various drainage projects in the Valley of Mexico eventually dried Lake Texcoco, creating firm land that would connect the former island of Iztacalco to the rest of the area. The dry land from the lake was formed mostly through the creation of chinampas on which were grown flowers and vegetables.[6] However, from the 19th century to the first decades of the 20th, Iztacalco had a number of canals crisscrossing it, the main one being Canal de la Viga, earlier known as the Acequia Real.[11] The canal extended for 1,560 meters and was thirty meters wide.[9] This made Iztacalco an important strategic transit point between what is now the historic center of Mexico City and the agricultural areas to the south and east such as Chalco and Xochimilco .[10] One of the main docks here was at Zacatlalmanco, which had an important market attached to it.[6] The first steamship passed by here in 1850, connecting Mexico City and Chalco. The canal had a number of pedestrian bridges over it, such as the La Garita. These bridges also doubled as regulators for the canal's waters due to the floodgates on their supporting arches. The canal also functioned as a rural getaway for Mexico City dwellers, especially on Sundays. Until mid-century, the borough area remained rural with small houses of adobe and/or reeds/small branches. Small canoes called trajineras carried cargo and passengers among the various docks on this canal. The canals were filled with aquatic birds such as herons and a local species called chichicuilotes.[12] It was also the scene of one of the most popular festivals of the 19th century, the Viernes de Dolores (Friday of the Virgin of Sorrows), also known as the Fiesta de las Flores (Festival of the Flowers). Starting in 1915, due to health concerns, the canal was closed to traffic and filled into become current major road, with the process completed in the 1930s.[9]

Through the 19th century, the community of Iztacalco and Mexico City would remain entities mostly separated by farmland and chinampas. This was also true of a number of communities that are now part of the borough such as Mixiuhca, Zacatlalmanco, La Magdalena, Santa Ana, and San Matias.[8] Up until the 20th century, the territory remained a maze of chinampas divided by canals large and small with carp and even snakes.[10]

In 1855, the districts and municipalities of the Federal District were reorganized, with the municipality of Iztacalco consisting of the communities of San Matías, San Juanico, Santa Anita, Magdalena Atlacolpa, Asunción Aculco, Santa Cruz, Santiago, San Miguel, La Asunción, San Sebastián Zapotla, Los Reyes, San Francisco, San Antonio Zacahuisco as well as two ranches called Cedillo and De la Viga or De la Cruz Metlapalco. In the mid 19th century, the area's population was dominated by indigenous peoples. In 1892, there was land redistribution among the families of the area, consisting of 255 hectares what belonged to three ranches.[12]

Iztacalco was first incorporated as a municipality on March 5, 1862, as part of the Tlalpan prefecture, with a population of about 2,800.[12] In 1903, the municipality disappeared and merged with the prefecture of Guadalupe Hidalgo, one of the six divisions of the Federal District at the time. On December 31, 1928, the current borough was formed.[13]

The urban sprawl of Mexico City began to reach the borough in the first decades of the 20th century. As the canals were filled in, they were converted into the primary roadways which still remain today. Canal de la Viga is now Calzada de la Viga.[6][12] The first industries in the area were established in the middle of the 20th century as the area was at the city's periphery, but its proximity to the historic center made its urbanization quick.[6] The first industries in the areas were those making cardboard boxes, cushions, furniture, chemicals, and food processing. The installation of factories and housing developments changed Iztacalco from rural to completely urban in less than four decades. Since the 1930s and especially since the 1950s, land became divided into housing lots as the canals and swamps were drained into dry land. Most of this housing was for the working classes. These include neighborhoods such as La Cruz, Pantitlán and Granjas México to house workers for factories built in the same areas.[12] Some of the most dangerous neighborhoods of the city are located in this borough.[6]

Citizens of the borough began directly electing local officials in 2000, like the borough president and two representatives to Mexico City's government. The old delegación became an alcaldía headed by a mayor after the political reforms enacted in 2016.[14]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Economy

Iztacalco is ranked ninth in economic marginalization in Mexico City with over 32% considered to be living in poverty. Over 85% are considered to be at least moderately economically marginalized, the highest in the city.[5] As of 2007, about 55% of the population over the age of twelve is employed either in the formal or informal economy, with most of these between the ages of 35 and 39.[4][5] About 48% of those in the total workforce do not have work in the formal economy. Well over half the workforce is male but the percentage of women has been rising since 1990. 0.1% work in agriculture, 20.9% work in mining, construction, and manufacturing, and 75.7% work in commerce and services.[5]

Eleven percent of the borough and 11.7% of establishments are dedicated to industry and manufacturing, the second highest percentage in the city.[6][4] The Ciudad Deportiva de la Magdalena Mixihuca is the second largest industrial zone in Mexico City.[8] Just under 50% of establishments are in commerce and just over 37% are in services, but there are no major office buildings.[6][4] The borough has eleven hotels, one five-star, two four-star and four three-star.[4]

Transportation

The borough has 53.8 km of primary roadway, 5.7% of Mexico City's total, with 6,082,261m2 of paved surface.[4] Major thoroughfares include the Viaducto Río de la Piedad which borders the borough on the north going east-west and connecting to the Mexico City-Puebla highway. It is bordered on the east by the Anillo Periférico, with the Circuito Interior passing through the center. Near the old village of Iztacalco is Eje 3 Oriente and Calzada de la Viga. Other important roads include Eje 2, Eje 6 Sur, Eje 1 Oriente and Eje 5 Oriente.[6][3] Four lines of the Metro pass through the borough: Line 9, Line 1, Line 4 and Line 8. Three of these lines meet at Metro Pantitlán, a major hub of the transport system and a major connecting point for busses heading east into the State of Mexico. There are four lines of the trolleybus and Metrobús Line 2 passes through as well.[6]

- Metro stations

- Viaducto ملف:MetroDF Línea 2.svg

- Santa Anita ملف:MetroDF Línea 4.svg ملف:MetroDF Línea 8.svg

- Coyuya ملف:MetroDF Línea 8.svg

- Iztacalco ملف:MetroDF Línea 8.svg

- Ciudad Deportiva ملف:MetroDF Línea 9.svg

- Puebla ملف:MetroDF Línea 9.svg

- Pantitlán ملف:MetroDF Línea 1.svg

ملف:MetroDF Línea 9.svg ملف:MetroDF Línea A.svg

ملف:MetroDF Línea 9.svg ملف:MetroDF Línea A.svg - Agrícola Oriental ملف:MetroDF Línea A.svg

- Canal de San Juan ملف:MetroDF Línea A.svg

Education

There are twenty-three public daycare centers, run by various governmental agencies. There are 147 kindergartens, with 63 of these run by the delegation. There are 128 public primary schools. There are fifty-five public middle schools, thirty-five of which are general studies, and twenty are geared to vocational instruction. There are thirteen private middle schools.[5] High schools include Plantel 2 de la Escuela Nacional Preparatoria (UNAM), la Preparatoria Iztacalco, dependiente del Instituto de Educación Media Superior del Distrito Federal (IEMS-DF) and Plantel 3 del Colegio de Bachilleres Metropolitano.[6]

There are five centers dedicated to special education and nine centers that work with special needs children in the regular school system. There are fourteen vocational schools above the middle school level.[5] It has eleven public libraries, mostly serving elementary school-aged children. It has ten casas de cultura which mostly serve only the neighborhoods in which they are found.[6] 3.1% of the population is illiterate.[4] To combat high dropout rates, the government of Mexico City offers stipends to families of school-aged children as long as the children remain enrolled in public schools.[6]

The Unidad Profesional Interdisciplinaria en Ingeniería y Ciencias Sociales y Administrativas (UPIICSA) del Instituto Politécnico Nacional is located in the borough, which offers majors in engineering, computer science and administration.[6] The Escuela Normal de Educación Física trains physical education teachers.[5]

National public high schools in the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM)'s Escuela Nacional Preparatoria system include:

Public high schools of the Instituto de Educación Media Superior del Distrito Federal (IEMS) include:[16]

- Escuela Preparatoria Iztacalco "Felipe Carrillo Puerto"

References

- ^ أ ب ت "Principales Resultados del Censo de Vivienda y Población 2020" (PDF) (in الإسبانية). Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- ^ "Base de datos del IDS-2020". Consejo de Evaluación de la Ciudad de México.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ "Iztacalco" (in الإسبانية). Mexico City: Secretaría de Turismo del Distrito Federal. Archived from the original on October 2, 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز "Delegación Iztacalco" [Borough of Iztacalco] (in الإسبانية). Mexico City: Secretaría de Desarrollo Económico. 2007. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص "Demografía de la Delegación Iztacalco" [Demographics of the Borough of Iztacalco] (PDF) (in الإسبانية). Mexico City: Borough of Iztacalco. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 2, 2012. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع غ ف ق ك ل م ن هـ و ي أأ أب "Iztacalco". Enciclopedia de Los Municipios y Delegaciones de México - Distrito Federal (in الإسبانية). Mexico: INAFED. 2010. Archived from the original on February 21, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ^ Sandra Carrasco (August 31, 2011). "Disfruta dos días de ska y rock en Iztacalco" [Enjoy two days of ska and rock in Iztacalco]. El Universal (in الإسبانية). Mexico City. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "Historia y Tradiciones" [History and Traditions] (in الإسبانية). Mexico City: Borough of Iztacalco. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Quintanar Hinojosa, Beatriz, ed. (2011). "Barrios Mágicos". México Desconocio Guia Especial. Mexico City: editor Impressiones Aereas SA de CV: 131–135. ISSN 1870-9400.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Angeles González Gamio (October 15, 2006). "Iztacalco en la Historia oral" [Iztacalco in oral history]. La Jornada (in الإسبانية). Mexico City. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح "Origenes y Glifo de Iztacalco" [Origins and glyph of Itzacalco] (in الإسبانية). Mexico City: Borough of Iztacalco. Archived from the original on April 2, 2012. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "Iztacalco en el México independiente" [Iztacalgo in an independent Mexico] (in الإسبانية). Mexico City: Borough of Iztacalco. Archived from the original on April 2, 2012. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ^ Distrito Federal División Territorial de 1810 a 1995 (PDF) (in الإسبانية). Mexico: INEGI. 1996. ISBN 970-13-1494-8.

- ^ "Constitution of Mexico City" (PDF) (in الإسبانية). Gobierno de la Ciudad de México. Retrieved 2021-02-08.

- ^ Home page. Escuela Nacional Preparatoria 2 "Erasmo Castellanos Quinto"". Retrieved on June 27, 2014. "Av. Río Churubusco núm. 654 entre Apatlaco y Tezontle Col. Zapata Vela Del. Iztacalco c.p. 08040"

- ^ "Planteles Iztacalco." Instituto de Educación Media Superior del Distrito Federal. Retrieved on May 28, 2014.

External links

- (in إسپانية) Alcaldía de Iztacalco website