مصفوفة هاريس

مصفوفة هاريس Harris matrix هي أداة تـُستخدم تصوير التعاقب الزمني of archaeological contexts and thus the sequence of depositions and surfaces on a 'dry land' archaeological site, otherwise called a 'stratigraphic sequence'. The matrix reflects the relative position and stratigraphic contacts of observable stratigraphic units, or contexts. It was developed in 1973 in Winchester, England, by Dr. Edward C. Harris.

The concept of creating seriation diagrams of archaeological strata based on the physical relationship between strata had had some currency in Winchester and other urban centres in England prior to Harris's formalisation. One of the results of Harris's work, however, was the realisation that sites had to be excavated stratigraphically, in the reverse order to that in which they were created, without the use of arbitrary measures of stratification such as spits or planums [ك]. In his Principles of archaeological stratigraphy Harris first proposed the need for each unit of stratification to have its own graphic representation, usually in the form of a measured plan. In articulating the laws of archaeological stratigraphy and developing a system in which to demonstrate simply and graphically the sequence of deposition or truncation on a site, Harris, it has been argued,[ممن؟] has followed in the footsteps of notable stratigraphic archaeologists such as Mortimer Wheeler, without necessarily being a notable excavator himself.

Harris's work was a vital precursor to the development of single context planning by the Museum of London and also the development of land use diagrams, all facets of a suite of archaeological recording tools and techniques developed in the UK which allow in-depth analysis of complex archaeological data sets, usually from urban excavations.

قوانين هاريس للتعاقب الأثري للطبقات

The first four laws were published in 1979.[1] A fifth law has been added following papers presented at the "Interpreting Stratigraphy: a Review of the Art" conferences in the UK from 1992 to 2003.

قانون التراكب

In a series of layers and interfacial features, as originally created, the upper units of stratification are younger and the lower are older, for each must have been deposited on, or created by the removal of, a pre-existing mass of archaeological stratification.

قانون الأفقية الأصلية

Any archaeological layer deposited in an unconsolidated form will tend towards a horizontal disposition. Strata which are found with tilted surfaces were so originally deposited, or lie in conformity with the contours of a pre-existing basin of deposition.

قانون التواصل الأصلي

Any archaeological deposit, as originally laid down, will be bounded by the edge of the basin of deposition, or will thin down to a feather edge. Therefore, if any edge of the deposit is exposed in a vertical plane view, a part of its original extent must have been removed by excavation or erosion: its continuity must be sought, or its absence explained.

قانون التعاقب الطبقي

Any given unit of archaeological stratification takes its place in the stratigraphic sequence of a site from its position between the undermost of all units which lie above it and the uppermost of all those units which lie below it and with which it has a physical contact, all other superpositional relationships being regarded as redundant.

Law of original consolidation

This law makes the distinction between architectural stratigraphy and all other types in regard to three criteria:[2]

- When intact, architectural stratigraphy is of consolidated nature, as opposed to the loose or scattered below-ground remains. Erosion causes parts of buildings to become part of soil stratigraphy.[2]

- Architectural stratigraphy is characterised by human intentionality, which is only seldom the case with below-ground strata.[2]

- Gravity: architectural stratigraphy left in situ is pulled down by gravity, in combination with human or natural intervention, while below-ground stratigraphy is created by gravity. As a result, architectural stratigraphy scatters with time, the oldest parts being those which resisted the effect of time.[2]

في الاستخدام

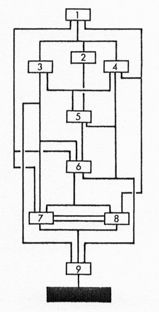

In constructing a matrix, the latest contexts sit on top of the matrix and the earliest at the bottom with the lines that link them together representing direct stratigraphic contact (though note that though all stratigraphic relationships are physical, not all physical relationships are stratigraphic). The matrix thus demonstrates the temporal relationship between any two units of archaeological stratification.[3] While excavating, it is best practice to compile the area and site stratigraphic matrices during the progress of an excavation through reference to both the drawn and written record. Regular daily checking of the record and the compilation of the matrix itself both help inform the individual archaeologist on the physical processes of site formation and highlight any areas where dubious relationships such as H relationships or loops in the recorded sequence may occur. Loops are sequences in the matrix that produce temporal anomalies so that the earliest context in a sequence of context appears to be later than the latest context by virtue of errors in excavation or recording.

Urban archaeological sites are complex affairs, often generating thousands of units of archaeological stratigraphy (contexts). It is of even more vital importance when excavating such sites to compile the matrix as the excavation progresses. Such sites by definition produce multi-linear sequences of succession and to date the best way to get a handle of these sequences is to compile the matrix by hand, based on the drawings and the context sheets. This ensures an internally consistent record and that the complexity of the site is given due regard. Computer programmes do exist which can aid the production of a matrix, though at the moment these tend towards articulating linear sequences rather than multi-linear sequences.

The Harris matrix is a tool that aids the accurate and consistent excavation of a site and articulates complex sequences in a clear and understandable way. Harris matrices play an invaluable role in the articulation of sequence and provide the building blocks from which higher order units of stratigraphically related events can be constructed.

مثال

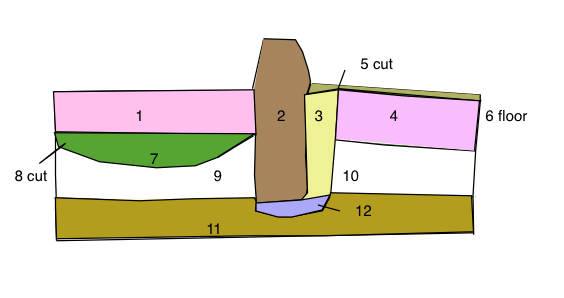

Take this hypothetical section as an example of matrix formation. Here there are twelve contexts, numbered thus:

- A horizontal layer

- Masonry wall remnant

- Backfill of the wall construction cut (sometimes called construction trench)

- A horizontal layer, probably the same as 1

- Construction cut for wall 2

- A clay floor abutting wall 2

- Fill of shallow cut 8

- Shallow pit cut

- A horizontal layer

- A horizontal layer, probably the same as 9

- Natural sterile ground formed before human occupation of the site

- Trample in the base of cut 5 formed by workmen's boots constructing the structure wall 2 and floor 6 is associated with.

The order in which these events occurred and the reverse order they should have been excavated with would be demonstrated by the following Harris matrix.

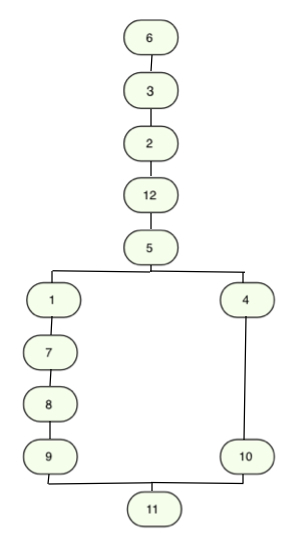

المصفوفة المكتملة

The later a context's formation is, the higher it is in the matrix, and conversely the earlier it is, the lower. Relationships between contexts are recorded in the sequence of formation, so even though wall 2 is physically higher than other contexts in section, its position in the matrix is immediately under backfill 3 and below floor 6. This is because the formation of the backfill and floor happened later. Also note the matrix splits into two parts below the construction cut 5. This is because the relationships across the section have been destroyed by the cutting of construction cut 5 and even if it is likely that layers 1 and 4 are probably the same deposit the information can not be guaranteed if the only information we had was this section. However the position of cut 5 and natural layer 11 "ties" the matrix together above and below the split in the matrix.

التفسير

Starting at the bottom, the order events occurred in this section is revealed by the matrix as follows. Natural ground formation 11 was followed by the laying down of layers 9 and 10 which "probably" occurred as the same event. Then a shallow pit 8 was cut and then back filled with 7. This pit feature in turn was "sealed" by the laying down of layer 1 which is probably the same event as layer 4. Following this a major change in land use occurs as construction cut 5 is dug and immediately followed by trample off the feet of people 12 working in the construction cut 5 who then build wall 2 after which they backfill excess space between the wall 2 and cut 5 with backfill 3. Finally clay floor 6 is laid down to the right of wall 2 over backfill 3 indicating a probable interior surface.

The nature of archaeological investigation and the subjective nature of all human experience means that a degree of interpretive activity obviously occurs during the process of excavation. The Harris matrix itself however serves to provide a check on observable quantifiable physical phenomena and relies on the excavator understanding which way in the sequence is 'up' and the ability of the excavator to excavate and record honestly, accurately and stratigraphically. The process of excavation destroys the context and requires the excavator to be able and willing to make informed (by experience and where necessary collaboration) decisions about which context or contexts lay at the top of the sequence.

As long as undercutting is not endemic, in practice onsite errors in judgment should become evident especially if temporary sections are kept for stratigraphic control in areas of a site that are hard to discern. However, archaeological sections, while being useful and valuable, only ever present a slice or caricature of a sequence, and often underrepresent its complexity. The use of archaeological sections when dealing with stratigraphic complexity is limited and their use should be context-sensitive rather than as a running arbiter of sequence.

مصفوفة كارڤر

Professor Martin Carver of the University of York has also developed a seriation diagram, known as the Carver matrix (not to be confused with the military term also named CARVER matrix). This diagram, which is based on the Harris matrix, is designed to represent the time lapse in use of recognizable archaeological entities such as floors and pits. Like Edward Harris, he used contexts numbered and defined on site as the basic elements of the sequence, but he added higher order groupings ("feature" and "structure") to increase the interpretive power. Several other people, such as Norman Hammond, looked to develop similar systems in the 1980s and 1990s.

انظر أيضاً

- Archaeological plan

- Archaeological association

- Cut (archaeology)

- Archaeological section

- Feature (archaeology)

- Chronological dating

- Reverse stratigraphy

المراجع والمصادر

المراجع

- ^ Harris, Edward C. (June 1979). "The laws of archaeological stratigraphy". World Archaeology. 11 (1): 111–117. doi:10.1080/00438243.1979.9979753. ISSN 0043-8243.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Harvey, Heather Maureen (1997). Imaging and Imagining the Past: The use of Illustrations in the Interpretation of Structural Development at the King's Castle, Castle Island, Bermuda (Thesis). Dissertations, Thesis, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626091. Williamsburg, VA: College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences. p. 20. doi:10.21220/s2-vexh-fs48. Retrieved 23 February 2022. (also at scholarworks.wm.edu.)

- ^ Ashmore, W., & Sharer, R. J. (2014). Page 106-107. In Discovering our past: A brief introduction to archaeology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

المصادر

- The MoLAS archaeological site manual MoLAS, London 1994. ISBN 0-904818-40-3. Rb 128pp. bl/wh

- Harris, Edward C.; (1979 & 1989). Principles of Archaeological Stratigraphy. 40 figs. 1 pl. 136 pp. London & New York: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-326651-3

- Harris, Edward C.; Brown III, Marley R.; & Brown, Gregory, J. (eds.) (1993). Practices of Archaeological Stratigraphy. London: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-326445-6.

- Roskams, Steve (Ed.) (2000). Interpreting Stratigraphy. Papers presented to the Interpreting Stratigraphy Conferences 1993-1997. BAR International Series 910. ISBN 1-84171-210-8.

وصلات خارجية

- Adrian Chadwick - Archaeology at the Edge of Chaos - Further Towards Reflexive Excavation Methodologies

- R. Thorpe - Which Way is Up? Context Formation & Transformation: The Life and Deaths of a Hot Bath in Beirut

- Free download of Principles of Archaeological Stratigraphy