مجلس العشرة

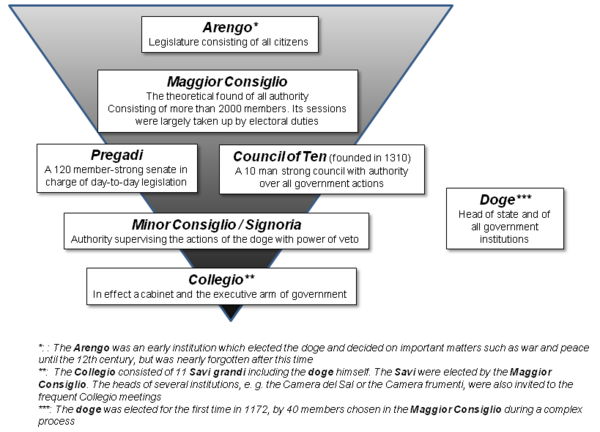

مجلس العشرة (إيطالية: Consiglio dei Dieci؛ Venetian: Consejo de i Diexe؛ إنگليزية: Council of Ten)، أو ببساطة العشرة, was from 1310 to 1797 one of the major governing bodies of the Republic of Venice. Elections took place annually and the Council of Ten had the power to impose punishments upon patricians. The Council of Ten had a broad jurisdictional mandate over matters of state security. The Council of Ten and the Full College constituted the inner circle of oligarchical patricians who effectively ruled the Republic of Venice.

الأصول

The Council of Ten was created in 1310 by Doge Pietro Gradenigo.[1] Originally created as a temporary body to investigate the plot of Bajamonte Tiepolo and Marco Querini, the powers of the Council were made formally permanent in 1455.[2] The Council was composed of ten patrician magistrates elected by the Great Council to one-year terms.[3] Until 1582, an additional zonta of around 15 to 20 members also served on the Council.[2] No more than one member of the same family could serve on the Council at any one time,[1] and members could not be re-elected to successive terms.[4]

التكوين

Elections took place annually in August and others in September.[3] The Council, which met at least weekly, had the power to impose punishments upon nobles, including banishment and capital punishment. On the council's orders, Doge Marino Faliero was executed in 1355, and the Count of Carmagnola in 1432.[5] The body's deliberations were highly secretive, and members of the Council of Ten took an oath of secrecy.[6] Thomas Madden wrote: "The three capi of the Ten served for a month at a time and, to avoid any opportunity for bribery, were forbidden to leave the Ducal Palace during their tenure of office."[7]

السلطات

Historian Edward Wallace Muir Jr. wrote: "The Council of Ten stood somewhat apart from the hierarchy of offices but was proverbially powerful. With its secret funds, system of anonymous informers, police powers, and broad jurisdictional mandate over matters of state security, the members of the Council of Ten, along with those of the Collegio, rotated offices among themselves and constituted the inner circle of oligarchical patricians who, in effect, ruled the republic."[2] During the War of the League of Cambrai, for example, the Council had responsibility for finding ways to pay for the state's military expenses.[8]

From the 1490s through the 1530s, the Council of Ten and other Venetian authorities enacted sumptuary laws.[9][10] In 1506, the Ten enacted an anti-banqueting law, seeking to prevent ambitious noblemen from engaging in vote buying by hosting lavish dinner parties at the compaginie della calza (exclusive social societies). The law specifically prohibited women other than the wives of members from attending such dinners.[11]

The Council was formally tasked with maintaining the security of the Republic and preserving the government from overthrow or corruption. However, its small size and ability to rapidly make decisions led to more mundane business being referred to it, and by 1457 it was enjoying almost unlimited authority over all governmental affairs. In particular, it oversaw Venice's diplomatic and intelligence services, managed its military affairs, and handled legal matters and enforcement. By the end of the sixteenth century, the Council of Ten had become Venice's spy chiefs, overseeing the city's vast intelligence network.[12]

The Council utilized bocche dei leoni (lion's mouths) placed around the city which allowed Venetians to report suspected illegal activities by placing a written note into the mouth. The lion's mouths were seen by later observers such as Mark Twain to represent an oppressive autocratic government that spied on its citizens, but in reality the reports placed in lion's mouths were examined and only credible reports were investigated.[7]

مفتشو الدولة

In 1539 the Council established the State Inquisitors, a tribunal of three judges chosen from among its members to deal with threats to state security. The Inquisitors were given equal authority to that of the entire Council of Ten, and could try and convict those accused of treason independently of their parent body. To further these activities, the Inquisitors created a large espionage network of spies and informants, both in Venice and abroad.[13] Inquisitors could conduct secret trials with a low standard of proof, and the inquisitors' practices bore strong similarities to those of the Roman Inquisition, which was established three years later.[14] From 1624 onward, the Council of Ten was charged with the prosecution of all crimes involving the private lives of Venetian patricians.[15]

المراجع

- ^ أ ب David Chambers & Brian Pullan with Jennifer Fletcher (eds.). Venice: A Documentary History, 1450-1630 (2001, reprinted 2004). University of Toronto Press/Renaissance Society of America. p. 55.

- ^ أ ب ت Edward Muir (1981). Civic Ritual in Renaissance Venice. Princeton University Press p. 20.

- ^ أ ب David Chambers & Brian Pullan with Jennifer Fletcher (eds.). Venice: A Documentary History, 1450-1630 (2001, reprinted 2004). University of Toronto Press/Renaissance Society of America. p. 54.

- ^ Edward Muir (1981). Civic Ritual in Renaissance Venice. Princeton University Press. p. 20.

- ^ David Chambers & Brian Pullan with Jennifer Fletcher (eds.). Venice: A Documentary History, 1450-1630 (2001, reprinted 2004). University of Toronto Press/Renaissance Society of America. pp. 55-56.

- ^ David Chambers & Brian Pullan with Jennifer Fletcher (eds.). Venice: A Documentary History, 1450-1630 (2001, reprinted 2004). University of Toronto Press/Renaissance Society of America. pp. 56-57.

- ^ أ ب Madden, Thomas F. (2012). Venice: A New History. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0147509802. OCLC 837179158.

- ^ David Michael D'Andrea, Civic Christianity in Renaissance Italy: The Hospital of Treviso, 1400-1530 (University of Rochester Press, 2007), p. 136.

- ^ Stanley Chojnacki, "Identity and Ideology in Renaissance Venice: The Third Serrata" in Venice Reconsidered: The History and Civilization of an Italian City-State, 1297–1797 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003) pp. 263-64

- ^ Edward Muir (1981). Civic Ritual in Renaissance Venice. Princeton University Press. p. 168.

- ^ Stanley Chojnacki, "Identity and Ideology in Renaissance Venice: The Third Serrata" in Venice Reconsidered: The History and Civilization of an Italian City-State, 1297–1797 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003) pp. 263-64.

- ^ Iordanou, Ioanna (2018). "The Spy Chiefs of Renaissance Venice: Intelligence Leadership in the Early Modern World". Spy Chiefs: Volume 2: Intelligence Leaders in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia (Georgetown University Press): 43–66.

- ^ Iordanou, I. (2015). "What News on the Rialto? The Trade of Information and Early Modern Venice's Centralized Intelligence Organization" (PDF). Intelligence and National Security. 31 (3): 305–326. doi:10.1080/02684527.2015.1041712. S2CID 155406514.

- ^ De Vivo, Filippo (2007). Information and Communication in Venice: Rethinking Early Modern Politics. Oxford University Press p. 34.

- ^ De Vivo, Filippo (2007) Information and Communication in Venice: Rethinking Early Modern Politics. Oxford University Press. p. 34.

المصادر

- Da Mosto, Andrea (1937). L'Archivio di Stato di Venezia. Indice Generale, Storico, Descrittivo ed Analitico. Tomo I: Archivi dell' Amministrazione Centrale della Repubblica Veneta e Archivi Notarili (in الإيطالية). Rome: Biblioteca d'arte editrice. OCLC 772861816.

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing إيطالية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing Venetian-language text

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- CS1 الإيطالية-language sources (it)

- Government of the Republic of Venice

- 1310 establishments in Europe

- 14th-century establishments in the Republic of Venice

- 1797 disestablishments in the Republic of Venice

- Anti-corruption agencies

- Defunct law enforcement agencies of Italy