شارل ريشيه

شارل ريشيه | |

|---|---|

Charles Robert Richet | |

شارل ريشيه | |

| وُلِدَ | أغسطس 25, 1850 |

| توفي | ديسمبر 4, 1935 (aged 85) |

| الجوائز | جائزة نوبل في الفسيولوجيا أو الطب (1913) |

| السيرة العلمية | |

| المجالات | الطب، فسيولوجيا وپاثولوجيا وبكتريولوجيا والتنويم المغناطيسي |

شارل روبير ريشيه Charles Robert Richet (عاش 26 أغسطس 1850 - 4 ديسمبر 1935) كان طبيب وعالم فسيولوجيا وپاثولوجيا وبكتريولوجيا فرنسي، حصل على جائزة نوبل في الطب عام 1913. صاغ، في 1902، مصطلح "تأق anaphylaxis" الذي يعني "ضد الحماية" ليصف موضوع بحثه، حين وجد أن جرعة لقاح ثانية من ذيفان شقائق نعمان البحر تتسبب في وفاة الكلب. فبدلاً من انتاج حصانة، كما هو متوقع في رد الفعل المعتاد للقاح، فإن الجرعة الأولى تخلـِّف حساسية تعرّض الحياة للخطر. وقد أدى ذلك إلى فهم مختلف ردود الأفعال الحساسية، وحمى القش والربو. كما قضى سنوات عديدة من عمره في دراسة الظواهر الروحانية.

حياته

في سنة 1887 عين ريشيه أستاذًا لعلم وظائف الأعضاء بالكوليج دو فرانس، وفي عام 1899 اختير عضوًا بأكاديمية الطب.

كان حصوله على جائزة نوبل في الطب سنة 1913 تقديرًا لأبحاثه عن ظاهرة التأق بالاشتراك مع بول بورتييه، وهي الأبحاث التي ساعدت في توضيح كنه حمى القش والربو وغيرهما من أمراض فرط الاستحساس للمواد الغريبة. في العام التالي لحصوله على جائزة نوبل اختير ريشيه عضوًا بأكاديمية العلوم الفرنسية.

كانت لريشيه اهتمامات متشعبة؛ إذ شملت كتاباته عددًا من الكتب في التاريخ وعلم الاجتماع والفلسفة وعلم النفس، كما كتب بعض المسرحيات والأشعار، وكان من رواد الطيران.

إلى جانب ذلك كان له اهتمام عميق بدراسة الإدراك فوق الحسي والتنويم المغناطيسي. وقد أسس دورية "حوليات العلوم النفسية" (بالفرنسية: Annales des sciences psychiques) سنة 1891، وظل طيلة حياته على صلة بعدد من مشاهير الروحانيين والمشتغلين بالعلوم الخفية في عصره مثل ألبرت فون شرينك-نوتزنگ وفريدريك وليام هنري مايرز وگابرييل ديلان.

في سنة 1905 اختير ريشيه رئيسًا لجمعية أبحاث الظواهر الخارقة إنگليزية: Society for Psychical Research بالمملكة المتحدة، وفي سنة 1919 صار رئيسًا شرفيًا للمعهد الدولي لعلوم ما وراء الطبيعة (بالفرنسية: Institut Métapsychique International) بباريس، ثم صار رئيسًا فعليًا له سنة 1929.

أعماله

اهتماماته الأخرى تضمنت الطيران: فقد جذبته تجارب إتيان-جول ماري Marey حول تحليق الطيور، فشارك ريشه في تصميم وإنشاء طائرة بريگيه-ريشه الدوارة، إحدى أوائل الطائرات التي جاوزت الأرض إلى عنان السماء بقدرتها الذاتية.

Parapsychology

Richet was deeply interested in the idea of extrasensory perception, and in hypnosis. In 1884, Alexandr Aksakov interested him in the medium of Eusapia Palladino.[بحاجة لمصدر] In 1891, Richet founded the Annales des sciences psychiques. He kept in touch with renowned occultists and spiritualists of his time such as Albert von Schrenck-Notzing, Frederic William Henry Myers and Gabriel Delanne.[بحاجة لمصدر] In 1919, Richet became honorary chairman of the Institut Métapsychique International in Paris, and, in 1930, its full-time president.[1]

Richet hoped to find a physical mechanism that would scientifically validate the existence of paranormal phenomena.[2] He wrote: "It has been shown that as regards subjective metapsychics the simplest and most rational explanation is to suppose the existence of a faculty of supernormal cognition ... setting in motion the human intelligence by certain vibrations that do not move the normal senses."[3] In 1905, Richet was named president of the Society for Psychical Research in the United Kingdom.[4]

In 1894, Richet coined the term ectoplasm.[5] Richet believed that some apparent mediumship could be explained physically as due to the external projection of a material substance (ectoplasm) from the body of the medium, but he didn't believe that this proposed substance had anything to do with spirits. He rejected the spirit hypothesis of mediumship as unscientific, instead supporting the sixth-sense hypothesis.[6][7] According to Richet:

It seems to me prudent not to give credence to the spiritistic hypothesis... it appears to me still (at the present time, at all events) improbable, for it contradicts (at least apparently) the most precise and definite data of physiology, whereas the hypothesis of the sixth sense is a new physiological notion which contradicts nothing that we learn from physiology. Consequently, although in certain rare cases spiritism supplies an apparently simpler explanation, I cannot bring myself to accept it. When we have fathomed the history of these unknown vibrations emanating from reality – past reality, present reality, and even future reality – we shall doubtless have given them an unwonted degree of importance. The history of the Hertzian waves shows us the ubiquity of these vibrations in the external world, imperceptible to our senses.[8]

He hypothesized a "sixth sense", an ability to perceive hypothetical vibrations, and he discussed this idea in his 1928 book Our Sixth Sense.[8] Although he believed in extrasensory perception, Richet did not believe in life after death or spirits.[6]

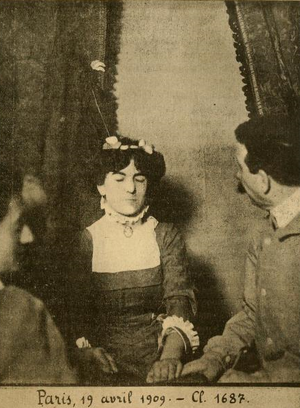

He investigated and studied various mediums, such as Eva Carrière, William Eglinton, Pascal Forthuny, Stefan Ossowiecki, Leonora Piper and Raphael Schermann.[6] From 1905 to 1910, Richet attended many séances led by the medium Linda Gazzera, claiming that she was a genuine medium who had performed psychokinesis, meaning that various objects had been moved in the séance room purely through the force of the mind.[6] Gazzera was exposed as a fraud in 1911.[9] Richet was also fooled into believing that Joaquin María Argamasilla, known as the "Spaniard with X-ray Eyes", had genuine psychic powers.[10] whom Harry Houdini exposed Argamasilla as a fraud in 1924.[11] According to Joseph McCabe, Richet was also duped by the fraudulent mediums Eva Carrière and Eusapia Palladino.[12]

The historian Ruth Brandon criticized Richet as credulous when it came to psychical research, pointing to "his will to believe, and his disinclination to accept any unpalatably contrary indications".[13]

تحسين النسل والمعتقدات العنصرية

Richet was a proponent of eugenics, advocating sterilization and marriage prohibition for those with mental disabilities.[14] He expressed his eugenist ideas in his 1919 book La Sélection Humaine.[15] From 1920 to 1926 he presided over the French Eugenics Society.[16]

Psychologist Gustav Jahoda has noted that Richet "was a firm believer in the inferiority of blacks",[17] comparing black people to apes, and intellectually to imbeciles.[18]

كتاباته

شملت كتابات ريشيه في علوم ما وراء الطبيعة ـ التي أصبحت محور كتاباته في أخريات حياته ـ عدة مؤلفات، من بينها:

- رسالة في الماورائيات (بالفرنسية: Traité de Métapsychique) ـ 1922

- حاستنا السادسة (بالفرنسية: Notre Sixième Sens) ـ 1928

- المستقبل والهاجس (بالفرنسية: L'Avenir et la Prémonition) ـ 1931

- الأمل الكبير (بالفرنسية: La grande espérance) ـ 1933

المراجع

- ^ "Charles Richet" Archived 11 مارس 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Institut Métapsychique International.

- ^ Alvarado, C. S. (2006). "Human radiations: Concepts of force in mesmerism, spiritualism and psychical research" (PDF). Journal of the Society for Psychical Research. 70: 138–162.

- ^ Richet, C. (1923). Thirty Years of Psychical Research. Translated from the second French edition. New York: Macmillan.

- ^ Berger, Arthur S; Berger, Joyce. (1995). Fear of the Unknown: Enlightened Aid-in-Dying. Praeger. p. 35. ISBN 0-275-94683-5 "In 1905, Professor Charles Richet, the French physiologist on the faculty of medicine of Paris and winner of the Nobel Prize in 1913, was made its president. Although he was a materialist and positivist, he was drawn to psychical research."

- ^ Blom, Jan Dirk. (2010). A Dictionary of Hallucinations. Springer. p. 168. ISBN 978-1-4419-1222-0

- ^ أ ب ت ث خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةTabori 1972 - ^ Ashby, Robert H. (1972). The Guidebook for the Study of Psychical Research. Rider. pp. 162–179

- ^ أ ب Richet, Charles. (nd, ca 1928). Our Sixth Sense. London: Rider. (First published in French, 1928)

- ^ McCabe, Joseph. (1920). Is Spiritualism Based On Fraud? The Evidence Given By Sir A. C. Doyle and Others Drastically Examined. London Watts & Co. pp. 33–34

- ^ Polidoro, Massimo. (2001). Final Séance: The Strange Friendship Between Houdini and Conan Doyle. Prometheus Books. pp. 171–172. ISBN 978-1591020868

- ^ Nickell, Joe. (2007). Adventures in Paranormal Investigation. The University Press of Kentucky. p. 215. ISBN 978-0813124674

- ^ McCabe, Joseph. (1920). Scientific Men and Spiritualism: A Skeptic's Analysis. The Living Age. 12 June. pp. 652–657.

- ^ Brandon, Ruth. (1983). The Spiritualists: The Passion for the Occult in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 135

- ^ Cassata, Francesco. (2011). Building the New Man: Eugenics, Racial Sciences and Genetics in Twentieth-Century Italy. Central European University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-963-9776-83-8

- ^ Mazliak, Laurent; Tazzioli, Rossana. (2009). Mathematicians at War: Volterra and His French Colleagues in World War I. Springer. p. 42. ISBN 978-90-481-2739-9

- ^ MacKellar, Calum; Bechtel, Christopher. (2014). The Ethics of the New Eugenics. Berghahn Books. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-1-78238-120-4

- ^ Gustav Jahoda. (1999). Images of Savages: Ancient Roots of Modern Prejudice in Western Culture. Routledge. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-415-18855-5

- ^ Bain, Paul G; Vaes, Jeroen; Leyens, Jacques Philippe. (2014). Humanness and Dehumanization. Routledge. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-84872-610-9

انظر أيضا

المصادر

وصلات خارجية

- Short biography and bibliography في المعمل الافتراضي في معهد ماكس پلانك لتاريخ العلوم

- Richet's Dictionnaire de physiologie (1895-1928) as fullscan from the original

- Charles Robert Richet photo

- Charles Richet Biography on Nobel Prize website

- سيرة قصيرة بقلم ناندور فودور في SurvivalAfterDeath.org.uk with links to several articles on psychical research

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2017

- مواليد 1850

- وفيات 1935

- أشخاص من پاريس

- أطباء فرنسيون

- فسيولوجيون فرنسيون

- حائزو جائزة نوبل في الطب

- حائزو جائزة نوبل فرنسيون

- تنويم مغناطيسي

- Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences

- French hypnotists

- French occultists

- أعضاء أكاديمية العلوم الفرنسية

- French writers on paranormal topics

- French parapsychologists

- White supremacists

- Grand Officers of the Legion of Honour