نارسس

| نارسس | |

|---|---|

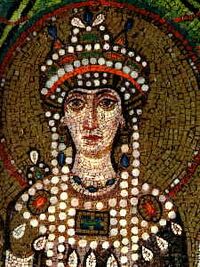

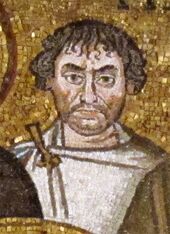

رجل أعتيد تقليدياً على تعريفه بأنه نارسس، من فسيفساء تصور جستنيان وحاشيته في بازيليكا سان ڤيتالى، راڤـِنـّا | |

| الاسم الأصلي |

|

| وُلد | 478 |

| توفى | 573 |

| الولاء | الإمبراطورية البيزنطية |

| الخدمة/الفرع | الجيش البيزنطي |

| الرتبة | جنرال |

| معارك/حروب | |

نارسس Narses (بالأرمينية: Նարսես; باليونانية: Ναρσής، 478–573) أحد الجنرالات في خدمة الإمبراطور البيزنطي جستنيان الأول خلال "إعادة الاستيلاء" التي وقعت خلال عهد جستنيان. وهو أرمني الأصل من أسرة كمساركن النبيلة والتي تدعي الانتساب إلى الأسرة الأشكانية في أرمينيا. قضى معظم حياته باعتباره خصياً مهماً نسبياً في قصور الأباطرة في القسطنطينية.

الأصول

وُلِد نارسس في الجزء الشرقي من أرمينيا الذي كان قد أُعطِيِ لفارس قبل مائة عام ضمن سلام أكيليسنى.[1] وكان من عائلة كمساركن الأرمنية النبيلة، التي كانت فرعاً من بيت كارن، العشيرة الپارثية النبيلة.[2][3][4] أول ذِكر له في مصدر رئيسي كان من پروكوپيوس في 530م.[5][بحاجة لمصدر أفضل] سنة ميلاد نارسس غير معروفة؛ وقد أعطى المؤرخون السنوات 478 و 479 و 480. كما أن سنة وفاته هي أيضاً غير معروفة، بتخمينات تتراوح بين 566 و 574، مما يعطيه عمراً يتراوح بين ستاً وثمانين وستاً وتسعين عند وفاته. عائلته ونسبه هما أيضاً مجهولتان تماماً، مع العديد من الحكايات المختلفة عن أصوله وكيف أصبح خصياً.

وقد وصفه أگاثياس من ميرينا كالتالي: "كان رجلاً ذا عقلٍ سديد، ماهر في التأقلم مع الأزمنة. ولم يك ضليعاً في الأدب ولا في الخطابة، [إلا أنه] استعاض عن ذلك بخصوبة ذكائه،" كما وًصِف كـ"رجل صغير لين العريكة، ولكنه أقوى وأمضى عزيمة مما يبدو."[6]

الدين

العمل

شغب نيكا

Narses had a limited involvement in the Nika riots in 532, in that he was instructed by Justinian or Theodora to take, from the treasury, funds sufficient to bribe the Blue Faction's leaders. Narses appealed to their party loyalty. He reminded them that Hypatius, the man they were about to declare emperor, was a Green, unlike Justinian, who supported the Blues. Either the money or his words were convincing, so that soon the Blues began to acclaim Justinian and turned against Hypatius and the Greens.[7] Narses himself may have been with the men that dragged Hypatius from the throne on the Imperial Stand.

الحياة العسكرية

الحرب لصالح كنيسة مصر

في 535 قام نارسس بمهمة دقيقة أخرى ، هذه المرة لثيودورا. كان الهدف هو الوصول إلى الإسكندرية في مصر لوضع الأسقف الوحداني ثيودوسيوس على رأس المسيحية المصرية ونفي خصمه (من العقيدة الأرثوذكسية) گايانو؛ على رأس 6000 رجل تمكن نارسس في 104 أيام من هزيمة أنصار گايانو وإعادة ثيودوسيوس إلى العرش الپاپوي.[8] ومع ذلك ، لم يستسلم المتمردون ونظموا ثورة جديدة. ظل نارسيس في الإسكندرية لمدة ستة عشر شهرًا يشن حربًا أهلية ضد المتمردين ، بل واضطر في إحدى المرات إلى إشعال النار في جزء من المدينة. في خريف عام 536 ، قرر ثيودوسيوس ، بسبب أعمال الشغب ، العودة إلى القسطنطينية ، تاركًا الإسكندرية على الأرجح مع نارسيس.[9]

في 537 ثيودوسيوس ، بعد أن رفض قبول عقيدة خلقيدونية، أُزيل من العرش الپاپوي وأُرسل إلى المنفى في دركوس في تراقيا. في مكانه انتُخب بولس الراهب الخلقيدوني على العرش البطريركي. لأول مرة منذ خمسين عامًا، لم يكن بطريرك الإسكندرية مؤمناً بأحادية الطبيعة.[8] وبهذا الفعل أصبح الانفصال نهائياً بين الخطين البطريركيين، القبطي والأرثوذكسي، مما جعل الانشقاق بين الكنيستين دائماً.[10]

- محاربة عبادة إيزيس

كما كان نارسس نشطاً للغاية في حملات الاضطهاد التي قام بها جستنيان ضد الوثنية. فحوالي عام 535، أرسله الامبراطور إلى فيلة بمصر، حيث كان معبد إيزيس لايزال نشطاً، للقضاء على العبادة. نارسس سجن الكهنة ونهب الهيكل. وفي 553، قام الأسقف المحلي تيودور بتحويل المعبد إلى كنيسة.[11]

العودة إلى إيطاليا

معركة تاجيناي

التكتيك و التنظيم الحربي

روما

معركة مون لاكاتاريوس

المعارك الأخيرة

السنوات الأخيرة

For the next twelve years, it is thought that Narses stayed in and "set about to reorganize" Italy.[12] Justinian sent Narses a series of new decrees known as "pragmatic sanctions". Many historians refer to Narses in this part of his career as an Exarch.[13] Narses completed some restoration projects in Italy but was unable to return Rome to its former splendor, though he did repair many of the bridges into the city and rebuild the city's walls.[14]

The last years of Narses' life are enveloped in mystery. Some historians believe Narses died in 567, while others assert that he died in 574, entailing that he may have reached the age of 96.

Legend has it that Narses was recalled to Constantinople for turning the Romans under his rule into virtual slaves, thereby upsetting the new Emperor Justin II and his wife, the Empress Sophia. Narses then retired to Naples. In an apocryphal but often retold story, Sophia sent Narses a golden distaff with the sarcastic message that he was invited to return to the palace and oversee the women's spinning, and Narses is said to have replied that he would spin a thread of which neither she nor Justin would ever find the end.[15] From Naples, Narses supposedly sent word to the Lombards inviting them to invade northern Italy.[16] The historian Dunlap questions whether there was hostility between the empress and Narses. Paul the Deacon wrote that his body was returned to Constantinople; and John of Ephesus wrote that Narses was buried in the presence of the Emperor and Empress in a Bithynian monastery founded by him.[17][18]

المصادر

- ^ Fauber. Narses. p. 4.

- ^ John H. Rosser. Historical Dictionary of Byzantium. – Scarecrow Press, 2011. – P. 199."Armenians were a significant minority within the empire. In the sixth century, Justinian I's General Narses was Armenian. The emperor Maurice (582—602) may have been Armenian. In the ninth and 10th centuries there were several Armenian emperors, including Leo V, Basil I, Romanos I Lekapenos, and John I Tzimiskes. Theodora, the wife of Theophilios, was Armenian."

- ^ "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica".

- ^ Kaldellis 2019, p. 59.

- ^ Procopius, History of the Wars I. xv.31. The Loeb Classical Library. Trans. H.B. Dewing. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1954) Vol. I 139.

- ^ Agathias Scholasticus cited by Fauber, L.H. Narses Hammer of the Goths. (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1990) 15.

- ^ Fauber. Narses. 39–40.

- ^ أ ب {{{author}}}, {{{title}}}, [[{{{publisher}}}]], [[{{{date}}}]]..

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةPLRE, p. 913 - ^ AA.VV. (2007). Yale University Press (ed.). The Architecture of Alexandria and Egypt, C. 300 B.C. to A.D. 700. Vol. 63. p. 251. ISBN 0-300-11555-5.

- ^ Metzger, B.M. (1960). New Testament Tools and Studies. E.J. Brill. p. 114. Retrieved 2014-12-07.

- ^ Browning. Justinian and Theodora. 234.

- ^ Fauber. Narses. 139.

- ^ Richmond, Ian A. The City Walls of Imperial Rome. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1930) 90.

- ^ "Narses • Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1911". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2021-01-06.

- ^ Fauber. Narses. 176–183.

- ^ Dunlap. Office of the Grand Chamberlain. 295–299.

- ^ Tougher, Shaun (2008). The Eunuch in Byzantine History and Society (in الإنجليزية). Routledge. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-135-23571-0.

Agathias. The Histories. Book II. Trans. Joseph D. Frendo. (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1975)

Ashby, T; R. A. L. Fell “The Via Flaminia.” The Journal of Roman Studies. (Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies, 1921) Vol. 11. 125-190.

Browning, Robert. Justinian and Theodora. (London: Thames & Hudson, rev. ed. 1987)

Bury. J.B. History of the Later Roman Empire. From the Death of Theodosius I to the Death of Justinian. Vol.II (London: Macmillan Press, 1958)

Cameron, Averil. Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity: AD 395-600. (London: Routledge, 1993.) 114.

Croke, Brian. “Jordanes and the Immediate Past.” Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, (Franz Steiner Verlag, 2005) Vol. 54, No. 4. 473-494.

Croke, Brian. “ Cassiodorus and the Getica of Jordanes.” Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. (Franz Steiner Verlag: 2005) Vol. 54, No. 4. 473-494.

Dunlap, James E. The Office of the Grand Chamberlain in the Later Roman and Byzantine Empires. (London: Macmillan Press, 1924)

Fauber, Lawrence. Narses: Hammer of the Goths. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990).

Greatrex, Geoffrey. “The Nika Riot: A Reappraisal.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies, (The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies, 1997) Vol. 117. 60-86.

Holmes, W.G. The Age of Justinian and Theodora. (London: Gorgias Press, 1905) Vol II

Hornblower, Simon, Anthony Spawforth. “Narses.” Oxford Classical Dictionary. (New York: Oxford, 2003.) 1027.

Kaegi, Walter Emil Jr. “The Contribution of Archery to the Turkish Conquest of Anatolia.” Speculum. (Medieval Academy of America, Jan. 1964) Vol. 39, No. 1. 96-108.

Kazhdan, Alexander P. “Narses.” Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.) 1024.

Lewis, Archibald R. Naval Power and Trade in the Mediterranean. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951)

Liddell Hart, B.H. Strategy. (New York: Frederick A Praeger, 1957)

Oman, C.W.C. The Art of War In the Middle Ages. (New York: Cornell University Press, 1953)

Paul the Deacon. History of the Langobards. Trans. William D. Foulke. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1907)

Procopius, History Of The Wars I. xv.31. The Loeb Classical Library. Trans. H.B. Dewing. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1954)

Rance, Philip. “Narses and the Battle of Taginae (Busta Gallorum) 552: Procopius and Sixth-Century Warfare.” Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, (Franz Steiner Verlag, 2005.) Vol. 54, No. 4. 424-472.

Richmond, Ian A. The City Walls of Imperial Rome. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1930)

Scholasticus, Evagrius. Ecclesiastical History. Trans. E. Walford (London: Samuel Bagster and Sons, 1846) Book iv.

Teall, John L. “The Barbarians in Justinian's Armies.” Speculum. (Medieval Academy of America, Apr. 1965). Vol. 40, No. 2. 294-322.

The Book of the Popes (Liber Pontificalis). Trans. L.R. Loomis. (Merchantville, NJ: Evolution Publishing, 2006)

قراءات أخرى

- L. H. Fauber, Narses, Hammer of the Goths: The Life and Times of Narses the Eunuch, St Martins Pr (January 1991) ISBN 0-312-04126-8

- Philip Rance, 'Narses and the Battle of Taginae (Busta Gallorum) 552: Procopius and sixth century warfare', Historia 54 (2005), 424–472.

- Weir, William. 50 Battles That Changed the World: The Conflicts That Most Influenced the Course of History. Savage, Md: Barnes and Noble Books. ISBN 0-7607-6609-6.

- Articles containing أرمنية-language text

- Articles containing Greek-language text

- All pages needing factual verification

- Wikipedia articles needing factual verification from April 2016

- جنرالات جستنيان الأول

- خصيان بيزنطيون

- أرمن بيزنطيون

- بيزنطيون من أصل أرمني

- بيزنطيون من أصل إيراني

- مواليد 478

- وفيات 573

- الحرب القوطية (535-554)

- مسيحيو القرن الخامس

- مسيحيو القرن السادس

- عائلة كمساركن

- Praepositi sacri cubiculi