ثريا اسفندياري

| Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiary | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Queen consort of Iran | |||||

| Tenure | 12 February 1951 – 15 March 1958 | ||||

| وُلِد | 22 يونيو 1932 Esfahan, Iran | ||||

| توفي | 26 أكتوبر 2001 (aged 69) Paris, France | ||||

| الدفن | |||||

| الزوج | |||||

| |||||

| الأب | Khalil Esfandiary Bakhtiary | ||||

| الأم | Eva Karl | ||||

| الديانة | Shia Islam, later Christianity | ||||

| المنصب | Actress (1965) | ||||

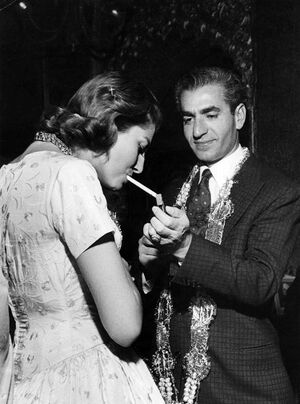

Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiary (فارسية: ثریا اسفندیاری بختیاری; 22 June 1932 – 26 October 2001) was the queen consort of Iran as the second wife of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, whom she married in 1951.

Their marriage suffered many pressures, particularly when it became clear that she was infertile. She rejected the Shah’s suggestion that he might take a second wife in order to produce an heir, as he rejected her suggestion that he might abdicate in favor of his half-brother. As the daughter of a German Christian mother, Soraya was mistrusted by Shiite clerics; she was also resented by the Shah’s possessive mother. In March 1958, the Shah wept as he announced their divorce. The British Ambassador claimed that Soraya was the Shah's only true love.

After a brief career as an actress, and a liaison with Italian film director Franco Indovina, Soraya lived alone in Paris until her death.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Early life and education

Soraya was the elder child and only daughter of Khalil Esfandiary Bakhtiary (1901–1983),[1] a Bakhtiari nobleman and Iranian ambassador to West Germany in the 1950s, and his Russian-born German wife Eva Karl (1906–1994).[2]

She was born in the English Missionary Hospital in Isfahan on 22 June 1932.[1][3] She had one sibling, a younger brother, Bijan (1937–2001). Her family had long been involved in the Iranian government and diplomatic corps. An uncle, Sardar Assad, was a leader in the Persian Constitutional Revolution of the early 20th century.[4] Soraya was raised in Berlin and Isfahan, and educated in London and Switzerland.[3]

Marriage

In 1948, Soraya was introduced to the recently divorced Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, by Forough Zafar Bakhtiary, a close relative of Soraya's, via a photograph taken by Goodarz Bakhtiary, in London, per Forough Zafar's request. At the time Soraya had completed high school at a Swiss finishing school and was studying the English language in London.[4] They were soon engaged: the Shah gave her a 22.37 carat (4.474 g) diamond engagement ring.[5]

الطلاق

Though the wedding took place during a heavy snow, deemed a good omen, the imperial couple's marriage had disintegrated by early 1958 owing to Soraya's apparent infertility. The Shah's only child, his daughter Princess Shahnaz, had married Ardeshir Zahedi, the son of the former Prime Minister, General Fazlollah Zahedi, a man who Mohammad Reza despised and had dismissed in 1955.[6] The Shah told Soraya that "a Zahedi could not continue the dynasty of the Pahlavis", and that she had to give him a son so the House of Pahlavi could continue.[7] She had sought treatment in Switzerland and France, and in St. Louis with Dr. William Masters.[8] The Shah suggested that he take a second wife to produce an heir, but she rejected that option.[9]

In an attempt to save her position as Queen, Soraya told the Shah that he should change the constitution of 1909 to allow one of his half-brothers to succeed him, which Mohammad Reza told her would require "the approval of the Council of the Wise Men" first.[7] Soraya, who had never read the constitution, did not know that there was no "Council of Wise Men", which was the Shah's way of putting off a difficult decision by lying.[7] Mohammad Reza had already amended the constitution twice, so he must have known there was no clause calling for a "Council of Wise Men" to approve amendments.[7] The Shah's domineering mother hated Soraya and was pressuring him to divorce her, telling him it was his duty to father a son to continue the House of Pahlavi.[7] Mohammad Reza persuaded Soraya to leave Iran while he promised he would call the "Council of Wise Men" to change the constitution.[7] Despite this promise, Soraya sensed her husband had turned against her, and before she left Iran one courtier remembered she had "systematically put her house in order".[7]

She left Iran in February and eventually went to her parents' home in Cologne, Germany, where the Shah sent his wife's uncle, Senator Sardar Assad in early March 1958, in a failed attempt to convince her to return to Iran.[10] Soraya rejected the offer that she remain queen while the Shah would take a second wife, writing in her memoirs that Mohammad Reza was "fundamentally an Oriental", drawing an unfavorable contrast with the Duke of Windsor "who sacrificed his throne for love", writing that only "Orientals" sacrificed love for their thrones.[7] On 5 March, Mohammad Reza phoned her to tell her she would have to accept him taking a second wife or else he would divorce her.[11] On 10 March, a council of advisers met with the Shah to discuss the situation of the troubled marriage and the lack of an heir.[12] Four days later, it was announced that the imperial couple would divorce. In a press statement issued by the Iranian government, it was announced that Soraya had agreed to the divorce while Soraya later claimed she had last heard from her husband on 5 March and she had not been informed beforehand.[11] It was, the 25-year-old queen said, "a sacrifice of my own happiness".[13] She later told reporters that her husband had no choice but to divorce her.[14] The British Ambassador to Iran reported "Soraya was the Shah's only true love" and he was "a man at an emotional cross-roads", who was happy to be able to marry again while unable to "bring himself to face it" that he had just divorced Soraya.[11]

On 21 March 1958, the Iranian New Year's Day, a weeping Shah announced his divorce to the Iranian people in a speech that was broadcast on radio and television; he said that he would not remarry in haste. The headline-making divorce inspired French writer Françoise Mallet-Joris to write a hit pop song, Je veux pleurer comme Soraya ("I Want to Cry Like Soraya"). The marriage was officially ended on 6 April 1958. According to a report in The New York Times, extensive negotiations had preceded the divorce in order to convince Queen Soraya to allow her husband to take a second wife. The Queen, however, citing what she called the sanctity of marriage, decided that "she could not accept the idea of sharing her husband's love with another woman."[9]

In a statement issued to the Iranian people from her parents' home in Germany, Soraya said, "Since His Imperial Majesty Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi has deemed it necessary that a successor to the throne must be of direct descent in the male line from generation to generation to generation, I will with my deepest regret in the interest of the future of the State and of the welfare of the people in accordance with the desire of His Majesty the Emperor sacrifice my own happiness, and I will declare my consent to a separation from His Imperial Majesty."[13] Soraya was well rewarded for the divorce with the Shah buying her a penthouse apartment in Paris that was valued at $3 million US, paying her a monthly alimony of $7,000 US (that continued to be paid until the Islamic Revolution overthrew Mohammad Reza in 1979), together with various luxuries such as a 1958 Rolls-Royce Phantom IV, a Mercedes-Benz 300 SL, a Bulgari ruby, a Van Cleef & Arpels brooch and a Harry Winston platinum ring with a 22.37-carat diamond that after her death was sold at the estate auction for $838,350 US.[11]

After the divorce, the Shah, who had told a reporter who asked about his feelings for the former Queen that "nobody can carry a torch longer than me", indicated his interest in marrying Princess Maria Gabriella of Savoy, a daughter of the deposed Italian king Umberto II. In an editorial about the rumors surrounding the marriage of "a Muslim sovereign and a Catholic princess", the Vatican newspaper, L'Osservatore Romano, considered the match "a grave danger".[15]

أفلام

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | Zwischen Glück und Krone | Herself | Archive Footage |

| 1965 | I tre volti | Herself/Linda /Mrs. Melville | |

| 1965 | She | Soraya | |

| 1998 | Legenden | Herself | Episode: "Soraya" |

References

- ^ أ ب "Princess Soraya Esfandiari". Bakhtiari family. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ Kadivar, Dairus (1 April 2007). "Stardust memories". The Middle East. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ أ ب "Earlier Marriages Ended in Divorce. Deposed Shah of Iran". The Leader Post. AP. 29 July 1980. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ^ أ ب "Shah To Wed, Iran Hears". The New York Times. 10 October 1950. p. 12.

- ^ "The Tribune, Chandigarh". The Tribune. India. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ^ Milani, Abbas The Shah, London: Macmillan, 2011, pages 212-213

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Milani, Abbas The Shah, London: Macmillan, 2011 page 213

- ^ Maier, Thomas (2013). "6". Masters of Sex. Basic Books.

- ^ أ ب "Iran Shah Divorces His Childless Queen". The New York Times. 14 March 1958. p. 2.

- ^ "Shah's Plea to Queen Held Vain". The New York Times. 6 March 1958. p. 3.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Milani, Abbas The Shah, London: Macmillan, 2011 page 214

- ^ "Iran Decision Pending". The New York Times. 11 March 1958. p. 2.

- ^ أ ب "Queen of Iran Accepts Divorce As Sacrifice", The New York Times, 14 March 1958, p. 4.

- ^ "Soraya Arrives for U.S. Holiday", The New York Times, 23 April 1958, p. 35.

- ^ Hofmann, Paul (24 February 1959). "Pope Bans Marriage of Princess to Shah". The New York Times. p. 1.

External links

- Princess Soraya, souvenirs about Internet lessons in Paris

- Photo gallery

- Another gallery of her

- Bakhtiari World

- ثريا اسفندياري at the Internet Movie Database

| الملكية الإيرانية | ||

|---|---|---|

| شاغر اللقب آخر من حمله Fawzia of Egypt

|

Queen consort of Iran 1951–1958 |

شاغر اللقب حمله بعد ذلك Farah Diba

|

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing فارسية-language text

- Pages with empty portal template

- 1932 births

- 2001 deaths

- Burials at the Westfriedhof (Munich)

- Converts to Roman Catholicism from Shia Islam

- Dames Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic

- French former Shia Muslims

- French people of German descent

- Grand Crosses Special Class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Iranian emigrants to France

- Iranian emigrants to Switzerland

- Iranian film actresses

- Iranian former Shia Muslims

- Iranian memoirists

- Iranian people of German descent

- Lur women

- People from Berlin

- People from Isfahan

- People of Pahlavi Iran

- Wives of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

- Iranian queens