تشيتشن إيتزا

Chichén Itzá | |

إل كاستيو يهيمن على مركز الموقع الأثري. | |

الموقع في وسط أمريكا | |

| المكان | يوكاتان، المكسيك |

|---|---|

| المنطقة | يوكاتان |

| الإحداثيات | 20°40′59″N 88°34′7″W / 20.68306°N 88.56861°W |

| التاريخ | |

| الفترات | أواخر الكلاسيكي إلى مطلع ما بعد الكلاسيكي |

| الثقافات | حضارة المايا |

| الاسم الرسمي | تشيتشن إيتسا، المدينة قبل الإسبانية Pre-Hispanic City of Chichen-Itza |

| النوع | ثقافي |

| المعيار | i, ii, iii |

| التوصيف | 1988 (12th session) |

| الرقم المرجعي | 483 |

| الدولة العضو | المكسيك |

| المنطقة | أمريكا اللاتينية والكاريبي |

تشيتشن إيتسا/إيتزا ( Chichén Itzá ؛ [nb 1] (وكثيراً ما تُتهجى Chichen Itza بالإنجليزية وفي اللغة التقليدية لمايا يوكاتك) كانت مدينة كبيرة قبل كلومبس بناها شعب المايا في الفترة الكلاسيكية النهائية. الموقع الأثري يقع في بلدية تينوم، ولاية يوكاتان، المكسيك.[1]

كانت تشيتشن إيتسا مركزاً رئيسياً في منخفضات المايا الشمالية منذ أواخر العصر الكلاسيكي (ح. 600-900 م) وطوال آخر الكلاسيكي (ح. 800-900 م) وإلى الجزء المبكر من فترة ما بعد الكلاسيكي (ح. 900-1200م). يعرض الموقع عدداً من الأنماط المعمارية، التي تـُذكـِّر بالأنماط المعهودة في وسط المكسيك وبنمطي پؤوك و تشنس في منخفضات المايا الشمالية. وجود أنماط وسط المكسيك كان يُظن أنه يمثل هجرة مباشرة أو حتى فتح عسكري من وسط المكسيك، إلا أن أحدث التفسيرات ترى وجود تلك الأنماط التي لا علاقة لها بالمايا هو نتيجة انتشار ثقافي.

تشيتشن إيتسا كانت واحدة من أكبر مدن المايا وربما كانت أحد المدن الكبرى الأسطورية، أو تولان، المشار إليها في أدب وسط أمريكا اللاحق.[2] ولعل المدينة كانت تضم أكبر تنوع سكاني في عالم المايا، وهو العامل الذي ربما أسهم في تنوع الأنماط المعمارية في الموقع.[3]

أطلال تشيتشن إيتسا هي ملك الحكومة الفدرالية، ورعاية الموقع هي من اختصاص المعهد الوطني للأنثروپولوجيا والتاريخ. الأرض تحت الآثار كانت ملكية خاصة حتى 29 مارس 2010، حين اشترتها ولاية يوكاتان.[nb 2]

تشيتشن إيتسا هي واحدة من أكثر الأماكن الأثرية اجتذاباً للزوار في المكسيك؛ إذ يزور آثارها نحو 2.6 مليون سائح سنوياً في 2017.[4]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الاسم والكتابة

The Maya name "Chichen Itza" means "At the mouth of the well of the Itza." This derives from chi', meaning "mouth" or "edge", and chʼen or chʼeʼen, meaning "well". Itzá is the name of an ethnic-lineage group that gained political and economic dominance of the northern peninsula. One possible translation for Itza is "enchanter (or enchantment) of the water,"[5] from its (itz), "sorcerer", and ha, "water".[6]

The name is spelled Chichén Itzá in Spanish, and the accents are sometimes maintained in other languages to show that both parts of the name are stressed on their final syllable. Other references prefer the modern Maya orthography, Chichʼen Itzaʼ (pronounced myn). هذه الصيغة تحافظة على التمييز الصوتي بين chʼ و ch، إذ أن الكلمة القاعدية هي chʼeʼen (التي، بالرغم من ذلك، غير مُشددة في المايا) تبدأ بالحرف الصامت postalveolar ejective affricate. التهجي التقليدية لمايا يوكاتك بالحروف اللاتينية، الذي اِستُخدِم منذ القرن 16 وحتى منتصف القرن العشرين، تهجاها "Chichen Itza" (as accents on the last syllable are usual for the language, they are not indicated as they are in Spanish). الكلمة "Itzaʼ" has a high tone on the "a" followed by a glottal stop (indicated by the apostrophe).

Evidence in the Chilam Balam books indicates another, earlier name for this city prior to the arrival of the Itza hegemony in northern Yucatán. While most sources agree the first word means seven, there is considerable debate as to the correct translation of the rest. This earlier name is difficult to define because of the absence of a single standard of orthography، ولكنها مُمثَلة بشكل مختلف كالتالي Uuc Yabnal ("البيوت السبعة الكبيرة"),[7] Uuc Hab Nal ("Seven Bushy Places"),[8] Uucyabnal ("الحكام السبعة العظام")[2] or Uc Abnal ("Seven Lines of Abnal").[nb 3] This name, dating to the Late Classic Period, is recorded both in the book of Chilam Balam de Chumayel and in hieroglyphic texts in the ruins.[9]

الموقع

تقع تشيتشن إيتسا في الجزء الشرقي من ولاية يوكاتان في المكسيك.[10] شمال شبه جزيرة يوكاتان قاحل وكل الأنهار داخله تجري تحت الأرض. وتوجد بالوعتان طبيعيتان كبيرتان، اسمهما سنوتى cenote، اللتين ربما كانتا تمدان تشيتشن بالماء طوال العام، مما جعلها جذابة للاستيطان. إحدى السنوتى، "سنوتى سگرادا Cenote Sagrado" أو السنوتى المقدسة (والتي تُعرف أيضاً بإسم البئر المقدس أو بئر التضحية)، هي الأكثر شهرة.[11]

النظام السياسي

الاقتصاد

كانت تشيتشن إيتسا قوة اقتصادية كبيرة في شمال منخفضات المايا في أوجها.[12] المشاركة في طريق التجاري المبحر حول شبه الجزيرة عبر مينائها في إسلا سرّيتوس على الساحل الشمالي،[13] كان بإمكان تشيتشن إيتسا الحصول على الموارد غير المتوفرة محلياً من أماكن بعيدة مثل السبج من وسط المكسيك والذهبمن جنوب أمريكا الوسطى.

وبين عامي 900م و 1050م توسعت تشيتشن إيتسا لتصبح عاصمة إقليمية قوية تسيطر على شمال ووسط يوكاتان. وقد أسست إسلا سرّيتوس كميناء تجاري.[14]

التاريخ

تطور شكل قلب موقع تشيتشن إيتسا أثناء الطور المبكر من وجودها، بين 750 و 900م.[15]

The layout of Chichén Itzá site core developed during its earlier phase of occupation, between 750 and 900 AD.[15] Its final layout was developed after 900 AD, and the 10th century saw the rise of the city as a regional capital controlling the area from central Yucatán to the north coast, with its power extending down the east and west coasts of the peninsula.[16] The earliest hieroglyphic date discovered at Chichen Itza is equivalent to 832 AD, while the last known date was recorded in the Osario temple in 998.[17]

التأسيس

The Late Classic city was centered upon the area to the southwest of the Xtoloc cenote, with the main architecture represented by the substructures now underlying the Las Monjas and Observatorio and the basal platform upon which they were built.[18]

الصعود

Chichén Itzá rose to regional prominence toward the end of the Early Classic period (roughly 600 AD). It was, however, toward the end of the Late Classic and into the early part of the Terminal Classic that the site became a major regional capital, centralizing and dominating political, sociocultural, economic, and ideological life in the northern Maya lowlands. The ascension of Chichen Itza roughly correlates with the decline and fragmentation of the major centers of the southern Maya lowlands.

As Chichén Itzá rose to prominence, the cities of Yaxuna (to the south) and Coba (to the east) were suffering decline. These two cities had been mutual allies, with Yaxuna dependent upon Coba. At some point in the 10th century Coba lost a significant portion of its territory, isolating Yaxuna, and Chichen Itza may have directly contributed to the collapse of both cities.[19]

الانحدار

According to some colonial Mayan sources (e.g., the Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel), Hunac Ceel, ruler of Mayapan, conquered Chichen Itza in the 13th century. Hunac Ceel supposedly prophesied his own rise to power. According to custom at the time, individuals thrown into the Cenote Sagrado were believed to have the power of prophecy if they survived. During one such ceremony, the chronicles state, there were no survivors, so Hunac Ceel leaped into the Cenote Sagrado, and when removed, prophesied his own ascension.

While there is some archeological evidence that indicates Chichén Itzá was at one time looted and sacked,[20] there appears to be greater evidence that it could not have been by Mayapan, at least not when Chichén Itzá was an active urban center. Archeological data now indicates that Chichen Itza declined as a regional center by 1100, before the rise of Mayapan. Ongoing research at the site of Mayapan may help resolve this chronological conundrum.

After Chichén Itzá elite activities ceased, the city may not have been abandoned. When the Spanish arrived, they found a thriving local population, although it is not clear from Spanish sources if these Maya were living in Chichen Itza proper, or a nearby settlement. The relatively high population density in the region was a factor in the conquistadors' decision to locate a capital there.[21] According to post-Conquest sources, both Spanish and Maya, the Cenote Sagrado remained a place of pilgrimage.[22]

الفتح الاسباني

الكونكيستادور الاسباني فرانشسكو دى مونتيخو (المخضرم من تجريدتي گريخالڤا و كورتيز) التمس بنجاح ميثاقاً من ملك اسبانيا لفتح يوكاتان. حملته الأولى في 1527، التي غطت معظم شبه جزيرة يوكاتان، بددت قواته ولكنها انتهت بتأسيس حصن صغير في شامان هاء، جنوب ما هو اليوم كانكون. عاد مونتيخو إلى يوكاتان في 1531 بتعزيزات وأسس قاعدته الرئيسية في كامپتشى على الساحل الغربي.[23] وأرسل ابنه، فرانشسكو مونيخو الأصغر، في أواخر 1532 لفتح داخل شبه جزيرة يوكاتان من الشمال. الهدف من البداية كان الذهاب إلى تشيتشن إيتسا وتأسيس عاصمة.[24]

أخيراً عاد مونتيخو إلى يوكاتان، وبتجنيده مايا من كامپتشى وتشامپوتون، بنى جيشاً هندو-اسباني كبير وفتح شبه الجزيرة.[25] ولاحقاً أصدر التاج الاسباني منحة ضمت تشيتشن إيتسا وبحلول 1588 كانت قد أصبحت مزرعة مواشي.[26]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التاريخ الحديث

دخلت تشيتشن إيتسا الخيال الشعبي في 1843 بصدور الكتاب أحداث السفر في يوكاتان Incidents of Travel in Yucatan بقلم جون لويد ستيفنز (برسوم توضيحية من فردريك كاثروود). الكتاب أعاد سرد زيارة ستيفنز ليوكاتان وتجواله في مدن المايا، بما فيها شيتشن إيتسا. وقد حفـَّز الكتاب استكشافات أخرى للمدينة. ففي 1860، مسح دزيريه شارنيه شيتشن إيتسا والتقط العديد من الصور التي نشرها في Cités et ruines américaines (1863).

Visitors to Chichén Itzá during the 1870s and 1880s came with photographic equipment and recorded more accurately the condition of several buildings.[27] In 1875, Augustus Le Plongeon and his wife Alice Dixon Le Plongeon visited Chichén, and excavated a statue of a figure on its back, knees drawn up, upper torso raised on its elbows with a plate on its stomach. Augustus Le Plongeon called it "Chaacmol" (later renamed "Chac Mool", which has been the term to describe all types of this statuary found in Mesoamerica). Teobert Maler and Alfred Maudslay explored Chichén in the 1880s and both spent several weeks at the site and took extensive photographs. Maudslay published the first long-form description of Chichen Itza in his book, Biologia Centrali-Americana.

In 1894 the United States Consul to Yucatán, Edward Herbert Thompson, purchased the Hacienda Chichén, which included the ruins of Chichen Itza. For 30 years, Thompson explored the ancient city. His discoveries included the earliest dated carving upon a lintel in the Temple of the Initial Series and the excavation of several graves in the Osario (High Priest's Temple). Thompson is most famous for dredging the Cenote Sagrado (Sacred Cenote) from 1904 to 1910, where he recovered artifacts of gold, copper and carved jade, as well as the first-ever examples of what were believed to be pre-Columbian Maya cloth and wooden weapons. Thompson shipped the bulk of the artifacts to the Peabody Museum at Harvard University.

In 1913, the Carnegie Institution accepted the proposal of archeologist Sylvanus G. Morley and committed to conduct long-term archeological research at Chichen Itza.[28] The Mexican Revolution and the following government instability, as well as World War I, delayed the project by a decade.[29]

In 1923, the Mexican government awarded the Carnegie Institution a 10-year permit (later extended another 10 years) to allow U.S. archeologists to conduct extensive excavation and restoration of Chichen Itza.[30] Carnegie researchers excavated and restored the Temple of Warriors and the Caracol, among other major buildings. At the same time, the Mexican government excavated and restored El Castillo (Temple of Kukulcán) and the Great Ball Court.[31]

In 1926, the Mexican government charged Edward Thompson with theft, claiming he stole the artifacts from the Cenote Sagrado and smuggled them out of the country. The government seized the Hacienda Chichén. Thompson, who was in the United States at the time, never returned to Yucatán. He wrote about his research and investigations of the Maya culture in a book People of the Serpent published in 1932. He died in New Jersey in 1935. In 1944 the Mexican Supreme Court ruled that Thompson had broken no laws and returned Chichen Itza to his heirs. The Thompsons sold the hacienda to tourism pioneer Fernando Barbachano Peon.[32]

There have been two later expeditions to recover artifacts from the Cenote Sagrado, in 1961 and 1967. The first was sponsored by the National Geographic, and the second by private interests. Both projects were supervised by Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH). INAH has conducted an ongoing effort to excavate and restore other monuments in the archeological zone, including the Osario, Akab Dzib, and several buildings in Chichén Viejo (Old Chichen).

In 2009, to investigate construction that predated El Castillo, Yucatec archeologists began excavations adjacent to El Castillo under the direction of Rafael (Rach) Cobos.

وصف الموقع

الأنماط المعمارية

الطراز المعماري پؤوك يتركز في منطقة تشيتشن القديمة، وكذلك المنشآت الأقدم في مجموعة الراهبات (بما في ذلك لاس مونخاس، الملحق ومباني لاس إگلسيا)؛ كما أنه ممثـَل في منشأ أكاب دزيب.[33] المبنى من طراز پؤوك بتسم بواجهة عليا مزخرفة بالفسيفساء المعتادة المميزة للطراز ولكنها تختلف عن عمارة پؤوك الأراضي الداخلية في جدران البلوكات الحجرية، بدلاً من الواجهات المنمقة في منطقة پؤوك نفسها.[34]

ثمة مبنى واحد على الأقل في مجموعة مونخاس بسمات واجهة مزخرفة وباب مقنـّع وهما مثالان نمطيان لطراز تشنس المعماري، وهو طراز متمركز بمنطقة شمال ولاية كامپتشى، ويقع بين منطقتي پؤوك و ريو بك.[35]

تلك المنشآت ذات الكتابات الهيروغليفية المنحوتة تتركز في مناطق معينة في الموقع، وأهمهم مجموعة لاس مونخاس.[36]

المجموعات المعمارية

المنصة الشمالية الكبرى

إل كاستيو

ويهيمن على المنصة الشمالية لتشيتشن إيتسا معبد كولكولكان (الثعبان ذو الريش، إله المايا) المماثل لإله الآزتك كتسالكواتل)، والذي عادة ما يشار إليه بإسم إل كاستيو ("القلعة").[37] هذا الهرم المدرج يرتفع 30 متر ويتكون من سلسلة من تسع شرفات مربعة، كل منها يبلغ ارتفاعها نحو 2.57 متر وبمعبد ارتفاعه ستة أمتار في القمة.[38]

ملعب الكرة القديم

تعرّف علماء الآثار على ثلاثة عشر ملعب كرة للعب الكرة في تشيتشن إيتسا،[39] إلا أن ملعب الكرة الأكبر الواقع على بعد 150 متر إلى الشمال الغربي للكاستيو هو بالتأكيد الأكثر إثارة للإعجاب. فهو الأكبر والأكثر حفاظاً بين ملاعب الكرة في وسط أمريكا القديمة.[37] وأبعاده 168×70 متر.[40]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

منشآت اضافية

سنوتى المقدسة

شبه جزيرة يوكاتان هي سهل من الحجر الجيري، بدون أنهار أو غدران. المنطقة مُخرَّمة بالبالوعات الطبيعية، التي تُسمى سنوتى cenotes، والتي تكشف مستوى المياه الجوفية للسطح. أحد أهم تلك البالوعات هي سنوتى سگرادو، التي يبلغ قطرها 60 متراً[41] ويحيط بها هاويات قص تنزل لمستوى الماء بانخفاض رأسي قدره 27 متر.

معبد المقاتلين

مجموعة الألف عمود

Along the south wall of the Temple of Warriors are a series of what are today exposed columns, although when the city was inhabited these would have supported an extensive roof system. The columns are in three distinct sections: A west group, that extends the lines of the front of the Temple of Warriors. A north group runs along the south wall of the Temple of Warriors and contains pillars with carvings of soldiers in bas-relief;

A northeast group, which apparently formed a small temple at the southeast corner of the Temple of Warriors, contains a rectangular decorated with carvings of people or gods, as well as animals and serpents. The northeast column temple also covers a small marvel of engineering, a channel that funnels all the rainwater from the complex some 40 meters (130 ft) away to a rejollada, a former cenote.

To the south of the Group of a Thousand Columns is a group of three, smaller, interconnected buildings. The Temple of the Carved Columns is a small elegant building that consists of a front gallery with an inner corridor that leads to an altar with a Chac Mool. There are also numerous columns with rich, bas-relief carvings of some 40 personages.

A section of the upper façade with a motif of x's and o's is displayed in front of the structure. The Temple of the Small Tables which is an unrestored mound. And the Thompson's Temple (referred to in some sources as Palace of Ahau Balam Kauil ), a small building with two levels that has friezes depicting Jaguars (balam in Maya) as well as glyphs of the Maya god Kahuil.

السوق

This square structure anchors the southern end of the Temple of Warriors complex. It is so named for the shelf of stone that surrounds a large gallery and patio that early explorers theorized was used to display wares as in a marketplace. Today, archeologists believe that its purpose was more ceremonial than commercial.

مجموعة أوساريو

South of the North Group is a smaller platform that has many important structures, several of which appear to be oriented toward the second largest cenote at Chichen Itza, Xtoloc.

The Osario itself, like the Temple of Kukulkan, is a step-pyramid temple dominating its platform, only on a smaller scale. Like its larger neighbor, it has four sides with staircases on each side. There is a temple on top, but unlike Kukulkan, at the center is an opening into the pyramid that leads to a natural cave 12 meters (39 ft) below. Edward H. Thompson excavated this cave in the late 19th century, and because he found several skeletons and artifacts such as jade beads, he named the structure The High Priests' Temple. Archeologists today believe neither that the structure was a tomb nor that the personages buried in it were priests.

The Temple of Xtoloc is a recently restored temple outside the Osario Platform is. It overlooks the other large cenote at Chichen Itza, named after the Maya word for iguana, "Xtoloc." The temple contains a series of pilasters carved with images of people, as well as representations of plants, birds, and mythological scenes.

Between the Xtoloc temple and the Osario are several aligned structures: The Platform of Venus, which is similar in design to the structure of the same name next to Kukulkan (El Castillo), the Platform of the Tombs, and a small, round structure that is unnamed. These three structures were constructed in a row extending from the Osario. Beyond them the Osario platform terminates in a wall, which contains an opening to a sacbe that runs several hundred feet to the Xtoloc temple.

South of the Osario, at the boundary of the platform, there are two small buildings that archeologists believe were residences for important personages. These have been named as the House of the Metates and the House of the Mestizas.

مجموعة البيت الملون

South of the Osario Group is another small platform that has several structures that are among the oldest in the Chichen Itza archeological zone.

The Casa Colorada (Spanish for "Red House") is one of the best preserved buildings at Chichen Itza. Significant red paint was still present in the days of the 19th century explorers. Its Maya name is Chichanchob, which according to INAH may mean "small holes". In one chamber there are extensive carved hieroglyphs that mention rulers of Chichen Itza and possibly of the nearby city of Ek Balam, and contain a Maya date inscribed which correlates to 869 AD, one of the oldest such dates found in all of Chichen Itza.

In 2009, INAH restored a small ball court that adjoined the back wall of the Casa Colorada.[42]

While the Casa Colorada is in a good state of preservation, other buildings in the group, with one exception, are decrepit mounds. One building is half standing, named La Casa del Venado (House of the Deer). This building's name has been long used by the local Maya, and some authors mention that it was named after a deer painting over stucco that doesn't exist anymore.[43]

المجموعة الوسطى

Las Monjas is one of the more notable structures at Chichen Itza. It is a complex of Terminal Classic buildings constructed in the Puuc architectural style. The Spanish named this complex Las Monjas ("The Nuns" or "The Nunnery"), but it was a governmental palace. Just to the east is a small temple (known as the La Iglesia, "The Church") decorated with elaborate masks.[44][45]

The Las Monjas group is distinguished by its concentration of hieroglyphic texts dating to the Late to Terminal Classic. These texts frequently mention a ruler by the name of Kʼakʼupakal.[17][46]

El Caracol ("The Snail") is located to the north of Las Monjas. It is a round building on a large square platform. It gets its name from the stone spiral staircase inside. The structure, with its unusual placement on the platform and its round shape (the others are rectangular, in keeping with Maya practice), is theorized to have been a proto-observatory with doors and windows aligned to astronomical events, specifically around the path of Venus as it traverses the heavens.[47]

Akab Dzib is located to the east of the Caracol. The name means, in Yucatec Mayan, "Dark Writing"; "dark" in the sense of "mysterious". An earlier name of the building, according to a translation of glyphs in the Casa Colorada, is Wa(k)wak Puh Ak Na, "the flat house with the excessive number of chambers", and it was the home of the administrator of Chichén Itzá, kokom Yahawal Choʼ Kʼakʼ.[48]

INAH completed a restoration of the building in 2007. It is relatively short, only 6 meters (20 ft) high, and is 50 meters (160 ft) in length and 15 meters (49 ft) wide. The long, western-facing façade has seven doorways. The eastern façade has only four doorways, broken by a large staircase that leads to the roof. This apparently was the front of the structure, and looks out over what is today a steep, dry, cenote.

The southern end of the building has one entrance. The door opens into a small chamber and on the opposite wall is another doorway, above which on the lintel are intricately carved glyphs—the "mysterious" or "obscure" writing that gives the building its name today. Under the lintel in the doorjamb is another carved panel of a seated figure surrounded by more glyphs. Inside one of the chambers, near the ceiling, is a painted hand print.

تشيتشن القديمة

Old Chichen (or Chichén Viejo in Spanish) is the name given to a group of structures to the south of the central site, where most of the Puuc-style architecture of the city is concentrated.[2] It includes the Initial Series Group, the Phallic Temple, the Platform of the Great Turtle, the Temple of the Owls, and the Temple of the Monkeys.

This section of the site has been closed to tourism for years while archaeological excavations and restorations were ongoing, and is planned to reopen to visitors in 2024.[49]

المنشآت الأخرى

Chichen Itza also has a variety of other structures densely packed in the ceremonial center of about 5 square kilometers (1.9 sq mi) and several outlying subsidiary sites.

كهوف بالانكانتشى

Approximately 4 km (2.5 mi) south east of the Chichen Itza archeological zone are a network of sacred caves known as Balankanche (إسپانية: Gruta de Balankanche), Balamkaʼancheʼ in Yucatec Maya). In the caves, a large selection of ancient pottery and idols may be seen still in the positions where they were left in pre-Columbian times.

The location of the cave has been well known in modern times. Edward Thompson and Alfred Tozzer visited it in 1905. A.S. Pearse and a team of biologists explored the cave in 1932 and 1936. E. Wyllys Andrews IV also explored the cave in the 1930s. Edwin Shook and R.E. Smith explored the cave on behalf of the Carnegie Institution in 1954, and dug several trenches to recover potsherds and other artifacts. Shook determined that the cave had been inhabited over a long period, at least from the Preclassic to the post-conquest era.[50]

On 15 September 1959, José Humberto Gómez, a local guide, discovered a false wall in the cave. Behind it he found an extended network of caves with significant quantities of undisturbed archeological remains, including pottery and stone-carved censers, stone implements and jewelry. INAH converted the cave into an underground museum, and the objects after being catalogued were returned to their original place so visitors can see them in situ.[51]

السياحة

Chichen Itza is one of the most visited archeological sites in Mexico; in 2017 it was estimated to have received 2.1 million visitors.[52]

Tourism has been a factor at Chichen Itza for more than a century. John Lloyd Stephens, who popularized the Maya Yucatán in the public's imagination with his book Incidents of Travel in Yucatan, inspired many to make a pilgrimage to Chichén Itzá. Even before the book was published, Benjamin Norman and Baron Emanuel von Friedrichsthal traveled to Chichen after meeting Stephens, and both published the results of what they found. Friedrichsthal was the first to photograph Chichen Itza, using the recently invented daguerreotype.[53]

After Edward Thompson in 1894 purchased the Hacienda Chichén, which included Chichen Itza, he received a constant stream of visitors. In 1910 he announced his intention to construct a hotel on his property, but abandoned those plans, probably because of the Mexican Revolution.

In the early 1920s, a group of Yucatecans, led by writer/photographer Francisco Gomez Rul, began working toward expanding tourism to Yucatán. They urged Governor Felipe Carrillo Puerto to build roads to the more famous monuments, including Chichen Itza. In 1923, Governor Carrillo Puerto officially opened the highway to Chichen Itza. Gomez Rul published one of the first guidebooks to Yucatán and the ruins.

Gomez Rul's son-in-law, Fernando Barbachano Peon (a grandnephew of former Yucatán Governor Miguel Barbachano), started Yucatán's first official tourism business in the early 1920s. He began by meeting passengers who arrived by steamship at Progreso, the port north of Mérida, and persuading them to spend a week in Yucatán, after which they would catch the next steamship to their next destination. In his first year Barbachano Peon reportedly was only able to convince seven passengers to leave the ship and join him on a tour. In the mid-1920s Barbachano Peon persuaded Edward Thompson to sell 5 acres (20,000 m2) next to Chichen for a hotel. In 1930, the Mayaland Hotel opened, just north of the Hacienda Chichén, which had been taken over by the Carnegie Institution.[54]

In 1944, Barbachano Peon purchased all of the Hacienda Chichén, including Chichen Itza, from the heirs of Edward Thompson.[32] Around that same time the Carnegie Institution completed its work at Chichen Itza and abandoned the Hacienda Chichén, which Barbachano turned into another seasonal hotel.

In 1972, Mexico enacted the Ley Federal Sobre Monumentos y Zonas Arqueológicas, Artísticas e Históricas (Federal Law over Monuments and Archeological, Artistic and Historic Sites) that put all the nation's pre-Columbian monuments, including those at Chichen Itza, under federal ownership.[55] There were now hundreds, if not thousands, of visitors every year to Chichen Itza, and more were expected with the development of the Cancún resort area to the east.

In the 1980s, Chichen Itza began to receive an influx of visitors on the day of the spring equinox. Today several thousand show up to see the light-and-shadow effect on the Temple of Kukulcán during which the feathered serpent appears to crawl down the side of the pyramid.[nb 4] Tour guides will also demonstrate a unique the acoustical effect at Chichen Itza: a handclap before the staircase of the El Castillo pyramid will produce by an echo that resembles the chirp of a bird, similar to that of the quetzal as investigated by Declercq.[56]

Chichen Itza, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is the second-most visited of Mexico's archeological sites.[57] The archeological site draws many visitors from the popular tourist resort of Cancún, who make a day trip on tour buses.

In 2007, Chichen Itza's Temple of Kukulcán (El Castillo) was named one of the New Seven Wonders of the World after a worldwide vote.[58] Despite the fact that the vote was sponsored by a commercial enterprise, and that its methodology was criticized, the vote was embraced by government and tourism officials in Mexico who projected that as a result of the publicity the number of tourists to Chichen would double by 2012.[nb 5][59] The ensuing publicity re-ignited debate in Mexico over the ownership of the site, which culminated on 29 March 2010 when the state of Yucatán purchased the land upon which the most recognized monuments rest from owner Hans Juergen Thies Barbachano.[60]

INAH, which manages the site, has closed a number of monuments to public access. While visitors can walk around them, they can no longer climb them or go inside their chambers. Climbing access to El Castillo was closed after a San Diego, California, woman fell to her death in 2006.[61]

معرض صور

انظر أيضاً

- الكويكب 100456 Chichen Itza

- قائمة المواقع الفلكية الأثرية مرتبة حسب البلد

- قائمة أهرامات وسط أمريكا

- Maya–Toltec controversy at Chichen Itza

- تيكال

- أوشمال

ملاحظات

- ^ /tʃiːˈtʃɛn iːˈtsɑː/، إسپانية: Chichén Itzá النطق الإسپاني: [tʃiˈtʃen iˈtsa]، tchee-TCHEN eet-SA وكثيرا ما ينقلب تشديد الحروف إلى /ˈtʃiːtʃɛn ˈiːtsə/ CHEE-chen EET-sə؛ من Yucatec Maya: Chiʼchʼèen Ìitshaʼ myn (Barrera Vásquez 1980)) "عند فم بئر شعب إيتسا"

- ^ فيما يتعلق بالأساس القانوني لملكية تشيتشن والمواقع الأخرى لأصل البلد، انظر Breglia (2006)، وخصوصاً الفصل الثالث، "Chichen Itza, a Century of Privatization". Regarding ongoing conflicts over the ownership of Chichen Itza, see Castañeda (2005). Regarding purchase, see "Yucatán: paga gobierno 220 mdp por terrenos de Chichén Itzá," La Jornada, 30 March 2010, retrieved 30 March 2010 from jornada.unam.mx

- ^ Uuc Yabnal becomes Uc Abnal, meaning the "Seven Abnals" or "Seven Lines of Abnal" where Abnal is a family name, according to Ralph L. Roys (Roys 1967, p. 133n7).

- ^ See Quetzil Castaneda (1996) In The Museum of Maya Culture (University of Minnesota Press) for a book length study of tourism at Chichen, including a chapter on the equinox ritual. For a 90-minute ethnographic documentary of new age spiritualism at the Equinox see Jeff Himpele and Castaneda (1997)[Incidents of Travel in Chichen Itza] (Documentary Educational Resources).

- ^ Figure is attributed to Francisco López Mena, director of the Consejo de Promoción Turística de México (CPTM – Council for the Promotion of Mexican Tourism).

الهامش

- ^ Gobierno del Estado de Yucatán 2007.

- ^ Miller 1999, p.26.

- ^ "Estadística de Visitantes" (in الإسبانية). INAH. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ Boot 2005, p. 37

- ^ Piña Chan 1993, p. 13

- ^ Luxton 1996, p. 141

- ^ Koch 2006, p. 19

- ^ Osorio León 2006, p. 458.

- ^ Osorio León 2006, p.456.

- ^ Coggins 1992.

- ^ Cobos Plama 2004, 2005, pp.539-540.

- ^ Cobos Palma 2004, 2005, p.540.

- ^ Cobos Palma 2004, 2005, pp.537-541.

- ^ أ ب Cobos Palma 2004, 2005, p.531. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "CobosPalma0405p531" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ Cobos Palma 2005, pp. 531–533

- ^ أ ب Osorio León 2006, p. 457.

- ^ Osorio León 2006, p. 461.

- ^ Cobos Palma 2005, p. 541

- ^ Thompson 1966, p. 137

- ^ Chamberlain 1948, pp. 136, 138

- ^ Restall 1998, pp. 81, 149; de Landa 1937, p. 90

- ^ Clendinnen 2003, p.23.

- ^ Chamberlain 1948, pp.19–20, 64, 97, 134–135.

- ^ Clendinnen 2003, p.41.

- ^ Breglia 2006, p.67.

- ^ Cobos, Rafael. "Chichén Itzá." In Davíd Carrasco (ed). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures. : Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 9780195188431

- ^ Morley 1913, pp. 61–91

- ^ Brunhouse 1971, pp. 74–75

- ^ Brunhouse 1971, pp. 195–196; Weeks and Hill 2006, p.111.

- ^ Brunhouse 1971, pp. 195–196; Weeks and Hill 2006, pp.577–653.

- ^ أ ب Usborne 2007

- ^ Sharer and Traxler 2006, pp.562-563.

- ^ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p.562. Coe 1999, pp.100, 139.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةOsorioLeon06p457 - ^ أ ب Cano 2002, p.84.

- ^ García Salgado 2010, p.118.

- ^ Kurjack et al. 1991, p.150.

- ^ Piña Chan 1980, 1993, p.42.

- ^ Cano 2002, p.85.

- ^ Fry 2009

- ^ El Chichán Chob y la Casa del Venado, Chichén Itzá, Yucatán. William J. Folan [1]

- ^ Cano 2002, p. 84.

- ^ Cano 2002, p. 87.

- ^ Osorio León 2006, p. 460.

- ^ Aveni 1997, pp. 135–138

- ^ Voss & Kremer 2000

- ^ "La 'Serie inicial' complejo urbano maya en Chichen Itzá abrirá en 2024". 11 February 2023.

- ^ Andrews 1961, pp. 28–31

- ^ Andrews 1970

- ^ "Yucatan cultural attractions are poised to break annual visitors record". The Yucatan Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2017-10-17. Retrieved 2019-01-18.

- ^ Palmquist & Kailbourn 2000, p. 252

- ^ Madeira 1931, pp. 108–109

- ^ Breglia 2006, pp. 45–46

- ^ Ball 2004

- ^ SECTUR 2006

- ^ "The New Seven Wonders of the World". Hindustan Times. July 8, 2007. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved July 11, 2007.

- ^ EFE 2007

- ^ Boffil Gómez 2010

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةDiarioYucatan3Mar06

ببليوگرافيا

- Andrews, Anthony P.; E. Wyllys Andrews V; Fernando Robles Castellanos (January 2003). "The Northern Maya Collapse and its Aftermath". Ancient Mesoamerica. New York: Cambridge University Press. 14 (1): 151–156. doi:10.1017/S095653610314103X. ISSN 0956-5361. OCLC 88518111.

- Andrews, E. Wyllys, IV (1961). "Excavations at the Gruta De Balankanche, 1959 (Appendix)". Preliminary Report on the 1959–60 Field Season National Geographic Society – Tulane University Dzibilchaltun Program: with grants in aid from National Science Foundation and American Philosophical Society. Middle American Research Institute Miscellaneous Series No 11. New Orleans: Middle American Research Institute, Tulane University. pp. 28–31. ISBN 0-939238-66-7. OCLC 5628735.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Andrews, E. Wyllys, IV (1970). Balancanche: Throne of the Tiger Priest. Middle American Research Institute Publication No 32. New Orleans: Middle American Research Institute, Tulane University. ISBN 0-939238-36-5. OCLC 639140.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Anda Alanís; Guillermo de (2007). "Sacrifice and Ritual Body Mutilation in Postclassical Maya Society: Taphonomy of the Human Remains from Chichén Itzá's Cenote Sagrado". In Vera Tiesler; Andrea Cucina (eds.). New Perspectives on Human Sacrifice and Ritual Body Treatments in Ancient Maya Society. Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology. Michael Jochim (series ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. pp. 190–208. ISBN 978-0-387-48871-4. ISSN 1568-2722. OCLC 81452956.

- Aveni, Anthony F. (1997). Stairways to the Stars: Skywatching in Three Great Ancient Cultures. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-15942-5. OCLC 35559005.

- Ball, Philip (14 December 2004). "News: Mystery of 'chirping' pyramid decoded". nature.com. Nature Publishing Group. doi:10.1038/news041213-5. Retrieved 2011-12-14.

- Barrera Vásquez, Alfredo (1980). Bastarrachea Manzano, Juan Ramón; Brito Sansores, William (eds.). Diccionario maya Cordemex: maya-español, español-maya. with collaborations by Refugio Vermont Salas, David Dzul Góngora, and Domingo Dzul Poot. Mérida, Mexico: Ediciones Cordemex. OCLC 7550928. (بالإسپانية) قالب:Yua icon

- Beyer, Hermann (1937). Studies on the Inscriptions of Chichen Itza (PDF Reprint). Contributions to American Archaeology, No.21. Washington D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington. OCLC 3143732. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

- Boffil Gómez; Luis A. (30 March 2007). "Yucatán compra 80 has en la zona de Chichén Itzá". La Jornada (in الإسبانية). Mexico City: DEMOS, Desarollo de Medios, S.A. de C.V. Retrieved 2011-12-14.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Boot, Erik (2005). Continuity and Change in Text and Image at Chichen Itza, Yucatan, Mexico: A Study of the Inscriptions, Iconography, and Architecture at a Late Classic to Early Postclassic Maya Site. CNWS Publications no. 135. Leiden, The Netherlands: CNWS Publications. ISBN 90-5789-100-X. OCLC 60520421.

- Breglia, Lisa (2006). Monumental Ambivalence: The Politics of Heritage. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71427-4. OCLC 68416845.

- Brunhouse, Robert (1971). Sylvanus Morley and the World of the Ancient Mayas. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-0961-9. OCLC 208428.

- Cano, Olga (January–February 2002). "Chichén Itzá, Yucatán (Guía de viajeros)". Arqueología Mexicana (in الإسبانية). Mexico: Editorial Raíces. IX (53): 80–87. ISSN 0188-8218. OCLC 29789840.

- Castañeda, Quetzil E. (1996). In the Museum of Maya Culture: Touring Chichén Itzá. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-2672-3. OCLC 34191010.

- Castañeda, Quetzil E. (May 2005). "On the Tourism Wars of Yucatán: Tíich', the Maya Presentation of Heritage" (Reprinted online as "Tourism “Wars” in the Yucatán", AN Commentaries). Anthropology News. Arlington, VA: American Anthropological Association. 46 (5): 8–9. doi:10.1525/an.2005.46.5.8.2. ISSN 1541-6151. OCLC 42453678. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

- Chamberlain, Robert S. (1948). The Conquest and Colonization of Yucatán 1517–1550. Washington D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington. OCLC 42251506.

- Charnay, Désiré (1886). "Reis naar Yucatán". De Aarde en haar Volken, 1886 (in الهولندية). Haarlem, Netherlands: Kruseman & Tjeenk Willink. OCLC 12339106. Project Gutenberg etext reproduction [#13346].

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Charnay, Désiré (1887). Ancient Cities of the New World: Being Voyages and Explorations in Mexico and Central America from 1857–1882. J. Gonino and Helen S. Conant (trans.). New York: Harper & Brothers. OCLC 2364125.

- Cirerol Sansores, Manuel (1948). "Chi Cheen Itsa": Archaeological Paradise of America. Mérida, Mexico: Talleres Graficos del Sudeste. OCLC 18029834.

- Clendinnen, Inga (2003). Ambivalent Conquests: Maya and Spaniard in Yucatán, 1517–1570. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37981-4. OCLC 50868309.

- Cobos Palma, Rafael (2005) [2004]. "Chichén Itzá: Settlement and Hegemony During the Terminal Classic Period". In Arthur A. Demarest; Prudence M. Rice; Don S. Rice (eds.). The Terminal Classic in the Maya Lowlands: Collapse, Transition, and Transformation (paperback ed.). Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. pp. 517–544. ISBN 0-87081-822-8. OCLC 61719499.

- Coe, Michael D. (1987). The Maya (4th edition, revised ed.). London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27455-X. OCLC 15895415.

- Coe, Michael D. (1999). The Maya. Ancient peoples and places series (6th edition, fully revised and expanded ed.). London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28066-5. OCLC 59432778.

- Coggins, Clemency Chase (1984). Cenote of Sacrifice: Maya Treasures from the Sacred Well at Chichen Itza. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-71098-4.

- Coggins, Clemency Chase (1992). Artifacts from the Cenote of Sacrifice, Chichén Itzá, Yucatán: Textiles, Basketry, Stone, Bone, Shell, Ceramics, Wood, Copal, Rubber, Other Organic Materials, and Mammalian Remains. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University; distributed by Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-87365-694-6. OCLC 26913402.

- Colas, Pierre R.; Alexander Voss (2006). "A Game of Life and Death – The Maya Ball Game". In Nikolai Grube (ed.) (ed.). Maya: Divine Kings of the Rain Forest. Eva Eggebrecht and Matthias Seidel (assistant eds.). Cologne, Germany: Könemann. pp. 186–191. ISBN 978-3-8331-1957-6. OCLC 71165439.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Cucina, Andrea; Vera Tiesler (2007). "New perspectives on human sacrifice and postsacrifical body treatments in ancient Maya society: Introduction". In Vera Tiesler and Andrea Cucina (eds.) (ed.). New Perspectives on Human Sacrifice and Ritual Body Treatments in Ancient Maya Society. Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology. Michael Jochim (series ed.). New York: Springer. pp. 1–13. ISBN 978-0-387-48871-4. ISSN 1568-2722. OCLC 81452956.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Demarest, Arthur (2004). Ancient Maya: The Rise and Fall of a Rainforest Civilization. Case Studies in Early Societies, No. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59224-0. OCLC 51438896.

- Diario de Yucatán (2006-03-03). "Fin a una exención para los mexicanos: Pagarán el día del equinoccio en la zona arqueológica". Diario de Yucatán (in الإسبانية). Mérida, Yucatán: Compañía Tipográfica Yucateca, S.A. de C.V. OCLC 29098719.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - EFE (29 June 2007). "Chichén Itzá podría duplicar visitantes en 5 años si es declarada maravilla" (in الإسبانية). Madrid, Spain. Agencia EFE, S.A.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Freidel, David. "Yaxuna Archaeological Survey: A Report of the 1988 Field Season" (PDF). Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies. Retrieved 2011-12-12.

- Fry, Steven M. (2009). "The Casa Colorada Ball Court: INAH Turns Mounds into Monuments". www.americanegypt.com. Mystery Lane Press. Retrieved 2011-12-14.

- García-Salgado, Tomás (2010). "The Sunlight Effect of the Kukulcán Pyramid or The History of a Line" (PDF). Nexus Network Journal. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- Gobierno del Estado de Yucatán (2007). "Municipios de Yucatán: Tinum" (in الإسبانية). Mérida, Yucatán: Gobierno del Estado de Yucatán. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

- Himpele, Jeffrey D. and Quetzil E. Castañeda (Filmmakers and Producers) (1997). Incidents of Travel in Chichén Itzá: A Visual Ethnography (Documentary (VHS and DVD)). Watertown, MA: Documentary Educational Resources. OCLC 38165182.

- Koch, Peter O. (2006). The Aztecs, the Conquistadors, and the Making of Mexican Culture. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. ISBN 0-7864-2252-1. OCLC 61362780.

- Kurjack, Edward B.; Ruben Maldonado C.; Merle Greene Robertson (1991). "Ballcourts of the Northern Maya Lowlands". In Vernon Scarborough and David R. Wilcox (eds.) (ed.). The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. pp. 145–159. ISBN 0-8165-1360-0. OCLC 51873028.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Landa, Diego de (1937). William Gates (trans.) (ed.). Yucatan Before and After the Conquest. Baltimore, Maryland: The Maya Society. OCLC 253690044.

- Luxton, Richard N. (trans.) (1996). The book of Chumayel : the counsel book of the Yucatec Maya, 1539-1638. Walnut Creek, California: Aegean Park Press. ISBN 0-89412-244-4. OCLC 33849348.

- Madeira, Percy (1931). An Aerial Expedition to Central America (Reprint ed.). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. OCLC 13437135.

- Masson, Marilyn (2006). "The Dynamics of Maturing Statehood in Postclassic Maya Civilization". In Nikolai Grube (ed.). Maya: Divine Kings of the Rain Forest. Eva Eggebrecht and Matthias Seidel (assistant eds.). Cologne, Germany: Könemann. pp. 340–353. ISBN 978-3-8331-1957-6. OCLC 71165439.

- Miller, Mary Ellen (1999). Maya Art and Architecture. London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20327-X. OCLC 41659173.

- Morley, Sylvanus Griswold (1913). W. H. R. Rivers; A. E. Jenks; S. G. Morley (eds.). Archaeological Research at the Ruins of Chichen Itza, Yucatan. Reports upon the Present Condition and Future Needs of the Science of Anthropology. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington. OCLC 562310877.

- Osorio León, José (2006). "XIX Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2005" (PDF). J.P. Laporte, B. Arroyo y H. Mejía: 455–462, Guatemala City, Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología. Retrieved on 2011-12-15.

- Palmquist, Peter E.; Thomas R. Kailbourn (2000). Pioneer Photographers of the Far West: A Biographical Dictionary, 1840–1865. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3883-1. OCLC 44089346.

- Pérez de Lara, Jorge (n.d.). "A Tour of Chichen Itza with a Brief History of the Site and its Archaeology". Mesoweb. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

- Perry, Richard D. (ed.) (2001). Exploring Yucatan: A Traveler's Anthology. Santa Barbara, CA: Espadaña Press. ISBN 0-9620811-4-0. OCLC 48261466.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Phillips, Charles (2007) [2006]. The Complete Illustrated History of the Aztecs & Maya: The definitive chronicle of the ancient peoples of Central America & Mexico - including the Aztec, Maya, Olmec, Mixtec, Toltec & Zapotec. London: Anness Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-84681-197-X. OCLC 642211652.

- Piña Chan, Román (1993) [1980]. Chichén Itzá: La ciudad de los brujos del agua (in الإسبانية). Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica. ISBN 968-16-0289-7. OCLC 7947748.

- Restall, Matthew (1998). Maya Conquistador. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-5506-9. OCLC 38746810.

- Roys, Ralph L. (trans.) (1967). The Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. OCLC 224990.

- Ruiz, Francisco Pérez. "Walled Compounds: An Interpretation of the Defensive System at Chichen Itza, Yucatan" (PDF). Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- Schele, Linda; David Freidel (1990). A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya (Reprint ed.). New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-688-11204-8. OCLC 145324300.

- Schmidt, Peter J. (2007). "Birds, Ceramics, and Cacao: New Excavations at Chichén Itzá, Yucatan". In Jeff Karl Kowalski; Cynthia Kristan-Graham (eds.). Twin Tollans: Chichén Itzá, Tula, and the Epiclassic to Early Postclassic Mesoamerican World. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection : Distributed by Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-88402-323-0. OCLC 71243931.

- SECTUR (2006). Compendio Estadístico del Turismo en México 2006. Mexico City: Secretaría de Turismo (SECTUR).

- SECTUR (7 July 2007). "Boletín 069: Declaran a Chichén Itzá Nueva Maravilla del Mundo Moderno" (in الإسبانية). Mexico City: Secretaría de Turismo. Retrieved 2011-12-16.

- Sharer, Robert J.; Loa P. Traxler (2006). The Ancient Maya (6th (fully revised) ed.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4817-9. OCLC 57577446.

- Thompson, J. Eric S. (1966) [1954]. The Rise and Fall of Maya Civilization. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-0301-9. OCLC 6611739.

- Tozzer, Alfred Marston; Glover Morrill Allen (1910). Animal figures in the Maya codices. Vol. 4 (Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Museum. OCLC 2199473.

- Usborne, David (7 November 2007). "Mexican standoff: the battle of Chichen Itza". The Independent. Independent News & Media. Retrieved 9 November 2007.

- Voss, Alexander W.; H. Juergen Kremer (2000). Pierre Robert Colas (ed.) (ed.). K'ak'-u-pakal, Hun-pik-tok' and the Kokom: The Political Organization of Chichén Itzá (PDF). Markt Schwaben, Germany: Verlag Anton Saurwein. ISBN 3-931419-04-5 OCLC 47871840.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|conference=ignored (help) - Weeks, John M.; Jane A. Hill (2006). The Carnegie Maya: the Carnegie Institution of Washington Maya Research Program, 1913–1957. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. ISBN 978-0-87081-833-2. OCLC 470645719.

- Willard, T.A. (1941). Kukulcan, the Bearded Conqueror : New Mayan Discoveries. Hollywood, California: Murray and Gee. OCLC 3491500.

للاستزادة

- Holmes, William H. (1895). Archeological Studies Among the Ancient Cities of Mexico. Chicago: Field Columbian Museum. OCLC 906592292.

- Spinden, Herbert J. (1913). A Study of Maya Art, Its Subject Matter and Historical Development. Cambridge, Mass.: The Museum. OCLC 1013513.

- Stephens, John L. (1843). Incidents of Travel in Yucatan. New York: Harper and Brothers. OCLC 656761248.

وصلات خارجية

- Chichen Itza at the Open Directory Project

- Encyclopaedia Britannica: Article on Chichen Itza

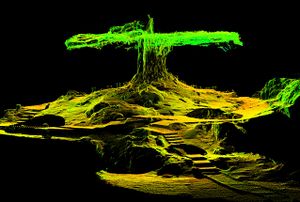

- Chichen Itza Digital Media Archive (creative commons-licensed photos, laser scans, panoramas), with particularly detailed information on El Caracol and el Castillo, using data from a National Science Foundation/CyArk research partnership

- UNESCO page about Chichen Itza World Heritage site

- Ancient Observatories page on Chichen Itza

- Chichen Itza reconstructed in 3D

- Archaeological documentation for Chichen Itza created by non-profit group INSIGHT and funded by the National Science Foundation and Chabot Space and Science Center

- Virtual Tour of Chichen Itza

- Articles containing إسپانية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing Yucatec Maya-language text

- CS1 الإسبانية-language sources (es)

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Pages using infobox ancient site with unknown parameters

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Portal templates with default image

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 errors: access-date without URL

- CS1 الهولندية-language sources (nl)

- CS1 errors: generic name

- مواقع التراث العالمي في المكسيك

- مواقع المايا

- تشيتشن إيتسا

- مواقع المايا في يوكاتان

- الفترة الكلاسيكية للمايا

- الفلك الأثري

- متاحف أثرية في المكسيك

- متاحف يوكاتان

- إيتسا

- National Monuments of Mexico

- أماكن مأهولة سابقاً في المكسيك

- أماكن مأهولة تأسست في القرن الثامن

- تأسيسات عقد 750 في حضارة المايا

- تأسيسات عقد 750 في المكسيك

- انحلالات القرن 13 في حضارة المايا

- انحلالات القرن 13 في المكسيك

- مقالات تحتوي مقاطع ڤيديو

- Tourist attractions in Yucatán