برنيس الثانية من مصر

| برنيس الثانية | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

عملة فئة ثمانية دراخمات لبرنيس الثانية. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ملكة قورينا الحاكمة | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| العهد | 258–247/246 ق.م.[1][2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| سبقه | ماگاس | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| تبعه | ضمتها المملكة الپلطيمة | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الحكم المشترك | ماگاس (حتى 250 ق.م.) دمتريوس (250–249 BCE) حكومة الجمهورية (249–246 ق.م.) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ملكة مصر | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| العهد | 246–221 ق.م.[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الحكم المشترك | پطليموس الثالث (246–222 BCE) پطليموس الرابع (222–221 ق.م.) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| وُلِد | ح. 267/266 ق.م. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| توفي | 221 ق.م. (45 أو 46 عاماً) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الزوج | دمتريوس الجميل پطليموس الثالث | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الأنجال | پطليموس الرابع أرسينوي الثالثة الإسكندر ماگاس برنيس | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الأسرة | الپطالمية | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الأب | ماگاس من قورينا | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الأم | أپاما الثانية | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

برنيس/برنيكه الثانية (Berenice II؛ و. 267 ق.م. أو 266 ق.م. - ت. 221 ق.م.)، كانت ابنة ماگاس قورينا والملكة أپاما، وهي زوجة پطليموس الثالث، وثالث حكام الأسرة الپطلمية في مصر.

في حوالي سنة 249 ق.م.، تزوجت الأمير المقدوني دميتريوس الجميل، بعيد وفاة والدها. إلا أنه بعد وصولهما إلى قورينا أصبح عشيقاً لأمها أپاما. وفي حدث درامي، أمرت بقتله في مخدع أپاما، إلا أن أپاما نجت. وكان ذلك في 248 أو 247 ق.م. ولم تنجب أطفالاً من دمتريوس. بعد ذلك تزوجت پطليموس الثالث. وقد أنجبا أربع أطفال: پطليموس الرابع، ماگاس، أرسينوي الثالثة وبرنيس. وقد لقت مصرعها على يد ابنها پطليموس الرابع سنة 221، مباشرة بعد أن أصبح فرعوناً.

أثناء غياب زوجها في الحرب السورية الثالثة، وهبت خصلة من شعرها إلى أفروديت ليعود سالماً، ووضعتها في معبد الإلهة في زفيريوم. وقد اختفت الخصلة بطريقة غامضة، كونون من ساموس شرح الظاهرة في عبارة بلاطية، بقوله أن الخصلة حـُمِلت إلى السماء ووضعت بين النجوم. هذه القصة تهكم عليها ألكسندر پوپ في قصيدته اغتصاب الخصلة.

الاسم كوما برنيسس Coma Berenices أو شعر برنيس، اُطلِق على كوكبة (أسماها العرب لاحقاً الهلبة)، لتخلد الحادث. كاليماخوس احتفى بالتحول في قصيدة، لم يبق منها سوى أبيات قليلة، إلا أن هناك ترجمة جيدة لها من كاتولوس.

وبعد وفاة زوجها بفترة قصيرة (221 ق.م.) قُـُتلت بأمر من ابنها پطليموس الرابع، الذي كانت غالباً تشاركه الحكم.

الاسم

| نوع الاسم | بالهيروغليفية | نقحرة — الصوت بالعربية | ||||||||||||||||||||

| «اسم حورس» (كـ حورس) |

|

|

[4] | zȝt-ḥqȝ jrt-n-ḥqȝ | ||||||||||||||||||

|

[5] | zȝt-ḥqȝ jrt-n-ḥqȝ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| «الاسم الشخصي» (كإبن رع) |

|

|

[6] | brnjkt (Βερενίκη) | ||||||||||||||||||

|

[7] | brnjkt Nṯrt mnḫ(t) mr(t)-nṯrwt | ||||||||||||||||||||

حياتها

عام 323 ق.م. دُمجت قورينا في المملكة الپلطمية، بواسطة پطليموس الأول بعد وقت قصير من وفاة الإسكندر الأكبر. تبينت صعوبة السيطرة على المنطقة وحوالي عام 300 ق.م، عهد پطليموس الأول بها إلى ماگاس، ابن زوجته برنيس الأولى من زواج سابق. بعد وفاة پطليموس الأول، أكد ماگاس استقلاله وخاض حرباً مع خليفته پطليموس الثاني. حوالي عام 275 ق.م، تزوج ماگاس من أپاما، التي تنحدر من السلوقيين، الذين أصبحوا أعداء للپطالمة.[8] كانت برنيس الثانية هي ابنتهما الوحيدة. وعندما جدد پطليموس الثاني جهوده للتوصل إلى تسوية مع ماگاس في أواخر ع. 250 ق.م، أُتفق على زواج برنيس من ابن عمها غير الشقيق، پطليموس الثالث المستقبلي، الذي كان وريث پطليموس الثاني.[9][10]

يزعم الفلكي گايوس يوليوس هيگينوس أنه عندما هُزم والد برنيس وقواته في المعركة، ركبت حصاناً، وحشدت القوات المتبقية، وقتلت العديد من الأعداء، ودفعت الباقين إلى التراجع.[11] صحة هذه القصة غير مؤكدة والمعركة المذكورة لم تُثبت بطريقة أخرى، لكن "الأمر ليس من المستحيل حدوثه".[12]

ملكة قورينا

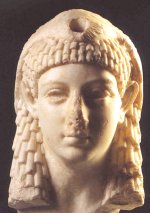

كُرمت برنيس بلقب باسيليسا (ملكة) على العملات المعدنية حتى في حياة والدها.[13] توجد عملات قورينية عليها صورة الملكة، والأسطورة ΒΕΡΕΝΙΚΗΣ ΒΑΣΙΛΙΣΣΗΣ (برنيس باسيليسا)، ومونوگرام اسم ماگاس. من الواضح أنه من الأكثر ترجيحاً أن هوية الملكة هي برنيس الثانية ابنة ماگاس وليس والدته برنيس الأولى، لأن الصورة لشابة ووجهها غير مكشوف، مما يعني أنها غير متزوجة.[14] وبحسب عملات برنيس، فإن توليها منصب ملكة قورينا كان عام 258 ق.م.[15]

توفي الملك ماگاس حوالي عام 250 ق.م. في هذه المرحلة، رفضت أپاما والدة برنيس احترام اتفاقية الزواج مع الپطالمة، وبدلاً من ذلك دعت أميراً من الأسرة الأنتيگونية يسمى دمتريوس، إلى قورينا للزواج من برنيس. بمساعدة أپاما ، استولى دمتريوس على السيطرة على المدينة. يُزعم أن دمتريوس وأپاما أصبحا عاشقين. يُقال إن برنيس رأتهما في السرير معاً وأمر باغتياله. ونجت أپاما.[16] ثم عُهد إلى حكومة جمهورية بالسيطرة على قورينا، بقيادة اثنين من القورينيين هما إكدلوس ودموفانيس، حتى زواج برنيس الفعلي من پطليموس الثالث عام 246 ق.م. بعد توليه العرش.[10][17] يبدو من المرجح أن برنيس قد تنازلت عن قدر معين من الحكم الذاتي لقورينا.[18]

ملكة مصر

عام 246 ق.م. تزوجت برنيس من پطليموس الثالث بعد توليه العرش.[17] أدى هذا إلى عودة قورينا إلى المملكة الپطلمية، حيث بقيت حتى تخلى عنها حفيد حفيدها الأكبر پطليموس أپيون للجمهورية الرومانية في وصيته عام 96 ق.م.

عبادتها كحاكمة

عام 244 أو 243 ق.م، دُمجت برنيس وزوجها في عبادة الدولة الپطلمية وعُبدت برنيس باعتبارهما إحدى الآلهة فاعلي الخير (Theoi Euergetai)، إلى جانب الإسكندر الأكبر والپطالمة الأوائل.[17][21] كانت برنيس تُعبد أيضاً كإلهة بمفردها، الإلهة فاعلة الخير (Thea Euergetis). وكثيراً ما كانت تُساوى بأفروديت وإيزيس، وارتبطت بشكل خاص بالحماية من غرق السفن. وتعود معظم الأدلة على هذه العبادة إلى عهد پطليموس الرابع أو ما بعده، لكن تأكدت عبادة تكريماً لها في الفيوم في عهد پطليموس الثالث.[22] تتشابه هذه العبادة بشكل وثيق مع العبادة التي كانت تُقدَّم لحماتها، أرسينوي الثانية، التي كانت تُساوى أيضاً بأفروديت وإيزيس، وتُربَط بالحماية من غرق السفن. كما يظهر التوازي أيضاً على العملات الذهبية التي سُكَّت بعد وفاتها تكريماً للملكتين. تحمل عملة أرسينوي الثانية زوجاً من قرون الوفرة على الوجه الخلفي، بينما تحمل عملة برنيس قرناً واحداً.

خصلة شعر برنيس

ترتبط ألوهية برنيس ارتباطاً وثيقاً بقصة "خصلة شعر برنيس". وفقاً لهذه القصة، تعهدت برنيس بالتضحية بشعرها الطويل كقربان نذري إذا عاد پطليموس الثالث سالماً من المعركة أثناء الحرب السورية الثالثة. وهبت برنيس خصلات شعرها لأفروديت ووضعتها في معبد رأس زفيريوم بالإسكندرية، حيث كانت تُعبد أرسينوي الثانية باعتبارها أفروديت، لكن في صباح اليوم التالي اختفت الخصلات. شرح الفلكي كونون من ساموس الظاهرة في عبارة بلاطية، بقوله أن الخصلة حـُمِلت إلى السماء ووضعت بين النجوم. تخليداً للحادث، أُطلق اسم كوما برنيسس Coma Berenices أو شعر برنيس، اُطلِق على كوكبة (أسماها العرب لاحقاً الهلبة).[23] من غير الواضح ما إذا كان هذا الحدث قد وقع قبل أو بعد عودة پطليموس؛ يقترح برانكو ڤان أوپن دي رويتيه أنه حدث بعد عودة پطليموس (حوالي مارس-يونيو أو مايو 245 ق.م).[24] كانت هذه الحلقة بمثابة ربط لبرنيس بالإلهة إيزيس كإلهة للبعث، حيث كان من المفترض أن تخصص خصلة من شعرها في كوپتوس حداداً على زوجها أوزيريس.[25][22]

انتشرت القصة على نطاق واسع في البلاط الپطلمي. صُنعت أختام تصور برنيس برأس محلوق وسمات إيزيس/دميتر.[26][22] احتفى الشاعر كاليماخوس، الذي كان يعمل في البلاط الپطلمي، بالحدث في قصيدة بعنوان قفل برينيس، والتي لم يتبق منها سوى بضعة أسطر.[27] كتب الشاعر الروماني كاتولوس في القرن الأول ق.م. ترجمة فضفاضة أو تعديلاً للقصيدة باللغة اللاتينية،[28] ويظهر ملخص نثري في كتاب في علم الفلك لهيگينوس.[11][23] أصبحت القصة شائعة في أوائل العصر الحديث عندما قام العديد من الرسامين الكلاسيكيين الجدد برسمها.

الألعاب الهلينية

انضمت برنيس إلى فريق العربات الحربية في الألعاب النيمية عام 243 أو 241 ق.م. وانتصرت. ويحتفى بهذا النجاح في قصيدة أخرى كتبها كاليماخوس بعنوان انتصار برنيس. تربط هذه القصيدة برنيس بالإلهة إيو، عشيقة زيوس في الأساطير اليونانية، والتي ربطها اليونانيون المعاصرون أيضاً بإيزيس.[29][22] عندما فازت في سباق العربات الحربية في الألعاب الأولمپبية في أوائل القرن الثالث ق.م، كلفت الشاعر پوسيديپوس بكتابة قصيدة قصيرة ادعت فيها صراحة أنها "سرقت" شهرة سينيسكا (κῦδος).[30] وقد ضُمنت قصيدتها في ما يسمى بالأنطولوجيا اليونانية، مما يشير أيضاً إلى استمرار أهميتها لفترة طويلة بعد النصر نفسه.[31]

وفاتها

توفي پطليموس الثالث في أواخر عام 222 ق.م. وخلفه پطليموس الرابع، ابنه من برنيس. توفيت برنيس بعد فترة وجيزة، في أوائل عام 221 ق.م. يذكر پوليبيوس أنها تعرضت للتسمم، كجزء من تطهير عام للعائلة المالكة من قبل الوصي الجديد للملك سوسيبيوس.[32][17] استمرت عبادتها كحاكم للدولة. وبحلول عام 211 ق.م، كانت لها كاهنة خاصة بها، وهي الأثلوفوروس ('حاملة الهبة')، التي سارت في مواكب بالإسكندرية خلف كاهن الإسكندر الأكبر والپطالمة، وكانيفوروس الإلهة أرسينوي الثانية.[12]

أنجالها

من پطليموس الثالث، أنجبت برنيس ستة أنجال:[33]

| الاسم | صورة | وُلد | توفى | ملاحظات |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| أرسينوي الثالثة |  |

246/5 ق.م. | 204 ق.م. | تزوجت شقيقها پطليموس الرابع عام 220 ق.م. |

| پطليموس الرابع |  |

مايو/يونيو 244 ق.م. | يوليو/أغسطس 204 ق.م. | ملك مصر في الفترة 222 - 204 ق.م. |

| ابن اسمه غير معروف | يوليو/أغسطس 243 ق.م. | ربما 221 ق.م. | الاسم غير معروف، ربما كان 'ليسيماخوس'. ربما قُتل أثناء أو قبل التطهير السياسي عام 221 ق.م.[34] | |

| الإسكندر | سبتمبر/أكتوبر 242 ق.م. | ربما 221 ق.م. | ربما قُتل أثناء أو قبل التطهير السياسي الذي حدث عام 221 ق.م.[35] | |

| ماگاس | نوفمبر/ديسمبر 241 ق.م. | 221 ق.م. | مات حرقاً في حمامه على يد ثيوگوس أو ثيودوتوس، بأمر من پطليموس الرابع.[36] | |

| برنيس | يناير/فبراير 239 ق.م. | فبراير/مارس 238 ق.م. | تم تأليهها بعد وفاتها في 7 مارس 238 ق.م. بموجب مرسوم كانوپي، باسم برنيس أناس پارثينون (برنيس، عشيقة العذارى).[37] |

حبها للعمران

المدينة السابقة لبنغازي الحالية أعادت تأسيسها برنيس ولذلك حملت اسمها.

آثارها

في يناير 2010، في كشف أثري كبير وهام ، عثرت بعثة المجلس المصري الأعلى للآثار في الإسكندرية على بقايا معبد يخص الملكة برنيس الثانية (246 - 222 ق.م)، وخبيئة كبيرة للتماثيل ضمت 600 تمثال من العصر الپطلمي مختلفة الأحجام والأنواع بمنطقة كوم الدكة. وأوضح محمد عبد المقصود رئيس البعثة الأثرية، أن ودائع الأساس الخاصة بالمعبد المكتشف، ويبلغ طوله 60 متراً وعرضه 15 متراً، ترجع إلى الملكة برنيس. وهى سابع وديعة يعثر عليها في الإسكندرية من العصر الپطلمي، وترجع أهميتها في أنها خاصة بأول معبد پطلمي للإلهة باستت، الممثلة على هيئة القطة، يكشف عنه في الإسكندرية.[38]

أيضا كشف عن قاعدة تمثال من حجر الجرانيت من عهد الملك پطليموس الرابع، عليها نقوش باليونانية القديمة من تسعة أسطر، توضح أن التمثال كان لشخص رفيع المستوى في محكمة الإسكندرية. ويؤرخ النقش لذكرى الانتصار في معركة رفح في 22 يونيو 217 ق.م.، التي انتصر فيها المصريون، وجنود من خمس جاليات مختلفة، على السلوقيين الذين كانوا يسيطرون على منطقة بلاد الشام القديمة، ولقد سجل الجنود الوثيقة في حب مصر والدفاع عنها، ضمن الحرب السورية الثالثة.

ويتضمن الكشف الأثري كذلك مجموعة من العناصر المعمارية القديمة، مثل صهريج وآبار للمياه بعمق 14 متراً تحت سطح الأرض من العصر الروماني من القرن الثالث الميلادي، وبقايا مخازن ومجارٍ للمياه من الحجر وبقايا حمام قديم وعدد من القطع الفخارية التي ترجع إلى القرن الرابع ق.م، وقطع فخار مستوردة من بحر إيجة ورودس بالبحر المتوسط. وقد جرى نقل المكتشفات إلى المخازن الأثرية لترميمها وحفظها تمهيداً لعرضها متحفياً. ويضيف عبد المقصود إن أقدم طبقات القطع الفخارية المكتشفة تعود إلى تاريخ أسبق من تأسيس مدينة الإسكندرية عام 332 ق.م، ويعتقد أن هذا الاكتشاف يقدم أدلة قوية على موقع الحي الملكي بمدينة الإسكندرية منذ تأسيسها، وهو واحد من أهم الاكتشافات الأثرية في تاريخ المدينة.

ذكراها

المذنـَّب 653 برنيس، المكتشـَف في 1907، مسمى أيضاً على اسم الملكة برنيس الثانية.

المصادر

- ديورانت, ول; ديورانت, أرييل. قصة الحضارة. ترجمة بقيادة زكي نجيب محمود.

وصلات خارجية

| Berenice II

]].مواقع خارجيه

- Salmonson, Jessica Amanda.(1991) The Encyclopedia of Amazons. Paragon House. Page 33. ISBN 1-55778-420-5

- The House of Ptolemy, Ch. 3

- Berenice II

- ^ Reginald Stuart Poole; British Museum Dept. of Coins and Medals (1883). Catalogue of Greek Coins: The Ptolemies, Kings of Egypt (in English). The Trustees. p. 59.

i. Queen Regnant of Cyrenaïca, ʙ.ᴄ. 258–247.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Libya Heads". guide2womenleaders.com. Retrieved 2022-12-25.

- ^ Stanwick, Paul Edmund (22 July 2010). Portraits of the Ptolemies: Greek Kings as Egyptian Pharaohs. University of Texas Press. p. xviii. ISBN 9780292787476.

- ^ C.R.Lepsius, Denkmäler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien, 12 Bde. Berlin 1849 — 59. -IV 9a.

- ^ K.Sethe, Hieroglyphische Urkunden der griech. — röm. Zeit, Leipzig 1904—122.

- ^ H.Brugsch, Thesaurus Inscriptionum Aegyptiacarum, 6 Bde., Leipzig 1883-91 —858.

- ^ C.R.Lepsius, Denkmäler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien, 12 Bde. Berlin 1849-59. — LD IV 17c.

- ^ Hölbl 2001, pp. 38–39

- ^ Justin 26.3.2

- ^ أ ب Hölbl 2001, pp. 44–46

- ^ أ ب Gaius Julius Hyginus De Astronomica 2.24

- ^ أ ب Clayman 2014, p. 157

- ^ Branko van Oppen de Ruiter (2016-02-03). Berenice II Euergetis: Essays in Early Hellenistic Queenship (in الإنجليزية). Springer. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-137-49462-7.

Remarkably, Berenice was hailed basilissa on coins even in her father's lifetime,

- ^ Branko van Oppen de Ruiter (2016-02-03). Berenice II Euergetis: Essays in Early Hellenistic Queenship (in الإنجليزية). Springer. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-137-49462-7.

- ^ Reginald Stuart Poole; British Museum Dept. of Coins and Medals (1883). Catalogue of Greek Coins: The Ptolemies, Kings of Egypt (in English). The Trustees. p. xxxii.

This review brings us to the accession of Berenice as queen of Cyrene, B.C. 258. Her coinage will be considered later (p. xlv.).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Justin 26.3.3-6; Catullus 66.25-28

- ^ أ ب ت ث Berenice II Archived فبراير 25, 2015 at the Wayback Machine by Chris Bennett

- ^ Reginald Stuart Poole; British Museum Dept. of Coins and Medals (1883). Catalogue of Greek Coins: The Ptolemies, Kings of Egypt (in English). The Trustees. p. xlviii.

But it seems most probable that Berenice conceded a certain degree of autonomy to Cyrene, which included the right of coining;

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Daszewski, W.A. (1986). "La personnification de la Tyché d'Alexandrie. Réinterprétation de certains monuments". In Kahil, L.; Auge, C.; Linant de Bellefonds, P. (eds.). Iconographie classique et identités régionales'. Paris: De Boccard. pp. 299–309.

- ^ Pfrommer, Michael; Towne-Markus, Elana (2001). Greek Gold from Hellenistic Egypt. Los Angeles: Getty Publications (J. Paul Getty Trust). ISBN 0-89236-633-8, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Hölbl 2001, p. 49

- ^ أ ب ت ث Hölbl 2001, p. 105

- ^ أ ب Barentine, John C. (2016). Uncharted Constellations: Asterisms, Single-Source and Rebrands. Springer. p. 17. ISBN 978-3-319-27619-9.

- ^ van Oppen de Ruiter 2016, p. 110

- ^ Plutarch, De Iside et Osiride 14.

- ^ Pantos, P. A. (1987). "Bérénice II Démèter". Bulletin des correspondence hellenique (in الفرنسية). 111: 343–352. doi:10.3406/bch.1987.1777.

- ^ Callimachus fragment 110 Pfeiffer.

- ^ Catullus 66

- ^ Parsons, P. J. (1977). "Callimachus: Victoria Berenices". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 25: 1–50.

- ^ Posidippus. "AB 87" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-04-20. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ "Greek Anthology 13.16". New York G.P. Putnam's sons.

- ^ Polybius 15.25.2; Zenobius 5.94

- ^ Dodson, Aidan and Hilton, Dyan. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2004. ISBN 0-500-05128-3

- ^ Lysimachus by Chris Bennett

- ^ Alexander by Chris Bennett

- ^ Magas by Chris Bennett

- ^ Berenice by Chris Bennett

- ^ طه علي (2010-01-20). "بعثة الآثار المصرية تكتشف أطلال معبد زوجة بطليموس الثالث في الإسكندرية". صحيفة الشرق الأوسط.