قضية اليد السوداء

The Black Hand (إسپانية: La Mano Negra) was a presumed secret, anarchist organization based in the Andalusian region of Spain and best known as the perpetrators of murders, arson, and crop fires in the early 1880s.[1] The events associated with the Black Hand took place in 1882 and 1883 amidst class struggle in the Andalusian countryside, the spread of anarcho-communism distinct from collectivist anarchism, and differences between legalists and illegalists in the Federación de Trabajadores de la Región Española.[2]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Background

Between the drought and poor harvests of 1881 and 1882, social tensions and hunger in Andalusia led to theft, robberies, and arson.[3] There were raids on farms and riots in protest of lack of work. Insurgents demanded that the town council give them jobs in public works. Among the most serious urban riots, on November 3, 1882, in Jerez de la Frontera, about 60 people were arrested as the Civil Guard and army intervened.[4] Owners were fearful of the rioters, who otherwise did not act in personal aggression or face farmhouse guards and the Civil Guard.[5]

The liberal press in Madrid denounced the dire circumstances of Andalusian day laborers in late 1882. An editorial in the newspaper El Imparcial described the looting of bakeries and butchers out of hunger, and having to choose between alms, theft, and death. Leopoldo Alas reported on hunger in Andalusia in a series of articles for El Día.[6]

By the end of 1882, the rains had returned and Andalusian agricultural laborers of the new Federación de Trabajadores de la Región Española decided to strike to raise their salaries at the prospect of a good harvest.[7][8]

History

Finding the Black Hand

In early November 1882, a member of the Civil Guard in Western Andalusia sent the government a discovered copy of the "regulations" of a secret socialist organization: la Mano Negra, or "the Black Hand". In the official report that accompanied it, these regulations proved the conspiracy of a group starting fires, felling forests, and murdering others over prior months. These regulations were two documents: "The Black Hand: Regulation of the Society of the Poor, against their thieves and executioners, Andalusia", and another simply titled, "Statutes", which did not use the phrase "Black Hand" but explained the governing rules of a People's Court to be established in each locality to punish crimes of the bourgeoisie. The former spoke of "the rich".[9]

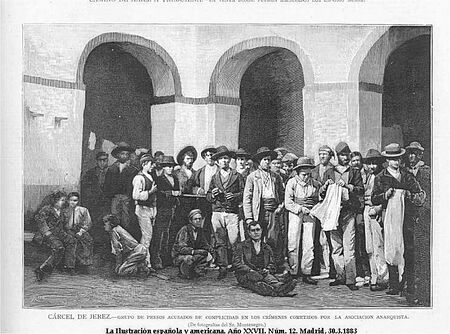

The government sent Civil Guard reinforcements to Cádiz province two weeks after receiving the documents. The 90 guardias arrived in Jerez on November 21 whereupon they proceeded, with the help of the Jerez municipal guard, to arrest many day laborers and FRTE members as assumed associates of the Black Hand. By early December, a newspaper reported that the guardias had captured hundreds of Black Hand internationalists, their weapons, and their documentation.[10]

Within several weeks, 3,000 day laborers and anarchists had been imprisoned,[8] though labor historian Josep Termes reported an even higher number: 2,000 in Cádiz and 3,000 in Jerez.[11] In reports sent to the Ministry of Labor, the most common reason for detention was membership in the Federación de Trabajadores (FTRE).[12] The federation's publication, Revista Social, decried the indiscriminate arrest of their members.[13]

Authenticating the documents

The authenticity of the documents, which the Civil Guard claimed to have found under a rock,[11] and its proof of the Black Hand's existence has been the subject of multiple historians. Manuel Tuñón de Lara thought that the document appeared fabricated. He doubted its test of authenticity to be legally or historically valid.[14] Josep Termes wrote that the Black Hand was a police fabrication and that the Civil Guard's found documents were from the older Núcleo Popular collection.[11]

Historian Clara Lida wrote that the underground documents' characteristics resembled those of the prior era and that the name "Black Hand" would inconspicuously fit alongside those of other European, clandestine groups in the anarchist and revolutionary tradition. The act of resurfacing documents from years ago to make dormant threats appear contemporary, Lida wrote, was a duplicitous manipulation of the sensationalist press to steer public opinion against the organized day laborers.[15]

Juan Avilés Farré wrote that the documents, most likely, were genuine but from two different organizations of unknown identity. The first document—"The Black Hand"—was likely acquired by the Jerez municipal guard several years earlier, sent by the Civil Guard to the Minister of War, and forgotten until someone attempted to solve the Jerez crimes of 1882. This document did not mention the First International. The second document came from the clandestine period of the First International's Spanish Regional Federation between 1873 and 1881.[16]

Crimes of the Black Hand

The Cádiz and Madrid press did not question the existence of the Black Hand and, instead, sensationalized it. El Cronista de Jerez wrote that members of the Black Hand were killed in punishment when unable to carry out an assassination.[10] The FTRE's Revista Social condemned the press's emphasis on treating news production as if it were a competition.[17]

The press focused on three crimes attributed to the Black Hand, with emphasis on two. After the first wave of arrests, on December 4, a married couple, innkeepers, were killed on the road to Trebujena, near Jerez de la Frontera. Two months later, on February 4, a young peasant named Bartolomé Gago, better known as "El Blanco de Benaocaz" was found interred in an open field on the outskirts of San José del Valle, near Jerez. The murder was later said to have occurred the same day as the innkeepers'.[18] This murder became known as the crime of Parrilla. Around the same time, a young ranch guard killed in August 1882 was discovered to have been caused not by accident but an assault to his abdomen.[19]

The government sent a special judge to Jerez to investigate the crimes in February 1883.[20] The Cortes also debated the matter in late February.[21]

Attempts to connect Mano Negra and the FTRE

The government, shopowners, and press—with the newspaper El Liberal as an exception[22]—associated the Black Hand with the Federación de Trabajadores (FTRE)[14] for two purposes, according to historian Clara Lida: to halt the International's growing influence in the country, and more locally, to forestall farm workers from organizing and striking against the coming harvest.[23]

The FTRE's Federal Committee denied any connection to the Black Hand and repeated its denouncement of violence through propaganda and any solidarity with such criminal groups. It emphasized the difference between the growing anarchosyndicalism of Catalonia and the illegalism of Andalusia.[24] The anarchist Peter Kropotkin's newspaper, Le Révolté, based in Geneva, sympathized with the workers attributed as part of the Black Hand and criticized the FTRE's lack of solidarity with them.[13]

In March, the FTRE's Federal Committee published a manifesto against the government's attempts to associate the federation with the Black Hand.[25]

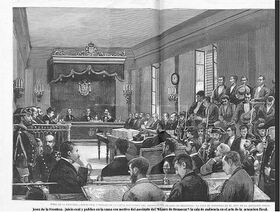

Legal proceedings

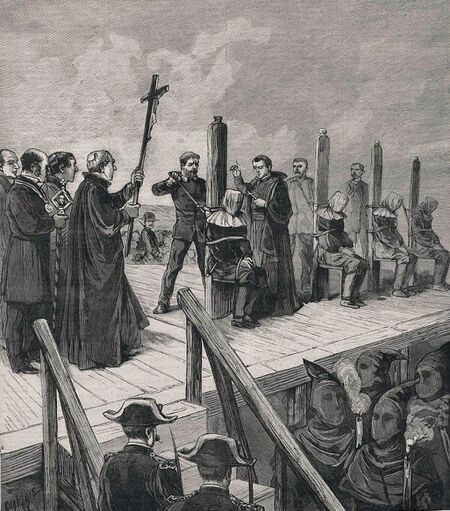

In June 1883, the Jerez court sentenced seven people and eight accomplices to 17 years and four months of prison. Two people were acquitted, but the prosecutor appealed the sentence to the Supreme Court, who ruled in April 1884 in favor of the death penalty for all but one accused. Nine sentences were commuted to jail time and seven were executed by garrote[26] two months later in Jerez de la Frontera's Plaza del Mercado. Three days later, the judges were recognized by the Order of Isabella the Catholic.[27]

In the murders of the innkeepers, one of the five people who attacked the husband at dawn on December 4 and stabbed the couple was shot dead at the scene of the crime. The other four were sentenced to death but never executed.[28] In the death of the ranch guard, two people were tried and one was sentenced to a long prison term.[29]

Afterwards, the FRTE's La Revista Social showed solidarity with workers but not with the condemned. In the clandestine newspaper of Los Desheredados, an illegalist and anarcho-communist group that had split from the FTRE, lamented that the Jerez executions went uncontested.[30]

Campaign in favor of the condemned

Nearly two decades later, the Madrid-based, anarchist newspaper Tierra y Libertad launched a campaign to release the eight convicts who remained in jail. Soledad Gustavo, partner of Joan Montseny, led the effort in January 1902 and was joined by other European newspapers, both anarchist and not. They held several meetings in Paris akin to those held in opposition to the Montjuïc trial. They portrayed the convicts as heroes of anarchism, among the first to fight social iniquities, and victims of a large crime against the proletariat. Accordingly, the group portrayed the murdered, including El Blanco de Benaocaz, as traitors and informers.[31]

The convicts denounced their crimes in letters to the newspapers, writing that their confessions were coerced through torture. The Spanish government attempted to fight the campaign until early 1903, when it commuted the sentences to exile.[32]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Consequences

The third congress of the FTRE, held in Valencia in October 1883, blamed the Black Hand affair for its reduced attendance.[33] The group again protested attempts to affiliate their organization with the Black Hand, condemned groups engaged in illegal acts, and agreed to dissolve the organization if it could not act legally.[34]

Josep Llunas, a member of the FTRE Federal Committee, accused the government of using the Black Hand as pretext to repress anarchists.[35]

Fallout from the Black Hand affair pressured the FTRE Federal Committee, based in Barcelona, to retreat from the Andalusian movement to avoid guilt by association. They did not contest the government and press accounts of events. The Andalusian federations, in turn, were immediately angered. The result was an unbridgeable chasm within the FTRE that contributed to its decline in membership and dissolution five years later.[36]

Historiographical debate

Historians offer differing accounts on the reality of the Black Hand organization. Tuñón de Lara affirms that there was no single organization, but small, anarcho-communist crime syndicates between secular rebellion and delinquency were used to justify the repression would precipitate the death of the FTRE.[37] Termes called the affair a police set-up while acknowledging that agrarian Andalusia did experience violence.[38]

Avilés Farré demurred that the question of the Black Hand's existence was less important than what became as a result: the documents were likely real, but there was ultimately no activity ascribed to the group or evidence that the group either successfully formed or committed any crimes. If the group existed, it left no trace and even those convicted of crimes associated with the Black Hand had not heard of the organization. The found documents were presented by the police as evidence of a broad conspiracy that would explain the wave of violence that had been occurring across western Andalusia. Its pugnacious name inferred a diffuse, mysterious fear, and had journalist appeal. While Avilés Farré interpreted the documents to be written by someone attempting to found a clandestine group for purposes of class warfare (i.e., not forged), likely by hidden associates of FTRE's San José del Valle local, the historian said that there was no evidence that the group came into fruition or carried out its proposed threats.[39] Whether the Black Hand affair was a false flag fabrication or, more simply, an unfounded government attempt to quell the agricultural revolts was the subject of Republican politician and writer Vicente Blasco Ibáñez's 1905 sociological novel, La bodega.[40]

Historian and journalist Juan Madrid wrote that the governmental interest in associating anarchists with any crime capable of tarnishing their image has been a constant throughout the history of Spain and the world.[41]

Legacy

The Mano Negra affair was the inspiration for a fictional South American guerrilla group in the comic series Condor written by the French writer Dominique Rousseau.[42] Reading this comic, French-Spanish singer Manu Chao was inspired to choose "Mano Negra" as the name of his band—a decision approved by his father, Ramón, a journalist living in exile in France after fleeing the Francoist dictatorship, who told him about the historical origins of the name.[42]

References

- ^ La Mano Negra: Historia de una represión by José Luis Pantoja Antúnez y Manuel Ramírez López

- ^ Termes 2011, p. 91.

- ^ Termes 2011, p. 81.

- ^ Avilés Farré 2013, p. 138-139.

- ^ Avilés Farré 2013, p. 139.

- ^ Avilés Farré 2013, p. 137-138.

- ^ Avilés Farré 2013, p. 138.

- ^ أ ب Lida 2010, p. 56-57.

- ^ Avilés Farré 2013, p. 139-141.

- ^ أ ب Avilés Farré 2013, p. 143-144.

- ^ أ ب ت Termes 2011, p. 92.

- ^ Avilés Farré 2013, p. 148.

- ^ أ ب Avilés Farré 2013, p. 151.

- ^ أ ب Tuñón de Lara 1977, p. 249.

- ^ Lida 2010, p. 51-52.

- ^ Avilés Farré 2013, p. 142-143.

- ^ Avilés Farré 2013, p. 150.

- ^ DOCUMENTO INÉDITO SOBRE LA MANO NEGRA: “Averiguación de lo ocurrido con respecto al suicidio del reo condenado a muerte Cayetano de la Cruz Expósito” La Alcubilla. Boletín Digital de Historia de Jerez, Nº 0. DICIEMBRE de 2016.

- ^ Avilés Farré 2013, p. 152.

- ^ Avilés Farré 2013, p. 144.

- ^ Avilés Farré 2013, p. 145-147.

- ^ Avilés Farré 2013, p. 149.

- ^ Lida 2010, p. 57-58.

- ^ Termes 2011, p. 84; 86.

- ^ Termes 2011, pp. 96-98.

- ^ Avilés Farré 2013, p. 157.

- ^ Luciano Boada y Valladolid, presidente, y Manuel López de Azcutia, teniente fiscal del Tribunal Supremo fueron condecorados con la Gran Cruz del Orden de Isabel la Católica. Véase: Diario oficial de avisos de Madrid 17.6.1884 Año CXXVI num.169

- ^ Avilés Farré 2013, p. 157-158.

- ^ Avilés Farré 2013, p. 158; 163.

- ^ Avilés Farré 2013, p. 158-159.

- ^ Avilés Farré 2013, p. 161-163.

- ^ Avilés Farré 2013, p. 163-164.

- ^ Tuñón de Lara 1977, pp. 251-252.

- ^ Termes 2011, p. 88; 99.

- ^ Tuñón de Lara 1977, p. 252.

- ^ Lida 2010, p. 58.

- ^ Tuñón de Lara 1977, p. 251.

- ^ Termes 2011, p. 91-92.

- ^ Avilés Farré 2013, p. 164-165.

- ^ La bodega

- ^ Diario bahía de Cádiz

- ^ أ ب Mortaigne, Véronique (17 January 2013). "Chapitre 4: La Mano Négra dévore la scène". Manu Chao, un nomade contemporain. Don Quichotte. ISBN 9782359491197. Retrieved 2015-08-04.

Bibliography

- Avilés Farré, Juan (2013). La Daga y la dinamita: los anarquistas y el nacimiento del terrorismo (in الإسبانية). Barcelona: Tusquets. ISBN 978-84-8383-753-5. OCLC 892212465.

- Lida, Clara E. (2010). "La Primera Internacional en España, entre la organización pública y la clandestinidad (1868–1889)". In Casanova, Julián (ed.). Tierra y Libertad. Cien años de anarquismo en España. Barcelona: Crítica. pp. 33–59. ISBN 978-84-9892-119-9. OCLC 758615483.

- Termes, Josep (2011). Historia del anarquismo en España (1870–1980). Barcelona: RBA. ISBN 978-84-9006-017-9.

- Tuñón de Lara, Manuel (1977). El movimiento obrero en la historia de España. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Barcelona: Laia. ISBN 978-84-7222-331-8.

Further reading

- Esenwein, George Richard (1989). "The "Black Hand" Mystery". Anarchist Ideology and the Working-class Movement in Spain, 1868-1898. University of California Press. pp. 84–. ISBN 978-0-520-06398-3.

- Grasso, Claudio (2016). "El caso de la Mano Negra en la reciente historiografía española". Hispania Nova (in الإسبانية) (14): 66–86. ISSN 1138-7319.

- Lida, Clara E. (ديسمبر 1969). "Agrarian Anarchism in Andalusia: Documents on the Mano Negra". International Review of Social History (in الإنجليزية). 14 (3): 315–352. doi:10.1017/S0020859000003643. ISSN 1469-512X.

- Kaplan, Temma (2015). Anarchists of Andalusia, 1868–1903 (in الإنجليزية). Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-6971-8. OCLC 949946764.

- Preston, Paul (2020). A People Betrayed: A History of Corruption, Political Incompetence and Social Division in Modern Spain. Liveright. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-87140-870-9.

- Yeoman, James Michael (2019). Print Culture and the Formation of the Anarchist Movement in Spain, 1890–1915 (in الإنجليزية). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-00-071215-5.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

External links

Media related to La Mano Negra at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to La Mano Negra at Wikimedia Commons

- Articles containing إسپانية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- CS1 الإسبانية-language sources (es)

- 1884 في السياسة

- 1883 in politics

- 1882 in politics

- 1884 in Spain

- 1883 in Spain

- 1882 in Spain

- Anarchism in Spain

- Defunct anarchist militant groups

- History of anarchism

- Conspiracy theories in Spain

- Secret societies in Spain

- Trials in Spain

- Anarchist organizations

- Province of Cádiz

- History of Andalusia