وارفارين

| نسرين حسون ساهم بشكل رئيسي في تحرير هذا المقال

|

| |

| |

| البيانات السريرية | |

|---|---|

| فئة السلامة أثناء الحمل |

|

| مسارات الدواء | وريدياً أو فموياً |

| رمز ATC | |

| الحالة القانونية | |

| الحالة القانونية | |

| بيانات الحركية الدوائية | |

| التوافر الحيوي | 100% |

| ارتباط الپروتين | 99.5% |

| الأيض | كبدي: CYP2C9, 2C19, 2C8, 2C18, 1A2 and 3A4 |

| Elimination half-life | 2.5 يوم |

| الإخراج | كلوي (92%) |

| المعرفات | |

| |

| رقم CAS | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.253 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

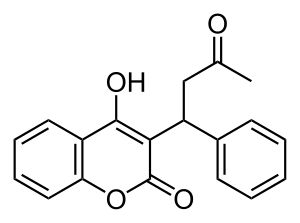

| التركيب | C19H16O4 |

| الكتلة المولية | 308.33 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| (verify) | |

إن الورافارين Warfarin هو مضاد تخثر (ويعرف بالأسماء التجارية التالية كومادين و جانتوڤين و ميرڤين و لاوارين). كان يباع سابقاً كمبيد للجرذان والفئران ولا يزال مشهوراً بهذا الاستخدام على الرغم من تطور سموم أقوى كالبروديفاكوم. وبعد عدة سنوات من استخدامه، وجد أن استخدامه فعّال وآمن نسبياً في منع تشكل الخثارات والانصمامات (هجرة وتشكل غير طبيعي للخثرات الدموية) في الكثير من الاضطرابات. وقد سُمِح باستخدامه كدواء في أوائل الخمسينيات من القرن الماضي 1950s وبقي شائعاً منذ ذلك الحين، فالوارفارين حالياً هو أكثر مضاد تخثر يصفه الأطباء في شمال أمريكا.[1]

ورغم فعالية الوارفارين، فإن له كثير من العيوب. حيث يوجد العديد من الأدوية التي تتداخل معه وكذلك يوجد مواد غذائية تتداخل معه لذلك يجب أن تراقب فعاليته دوماً من خلال فحص البروترومبين بالدم (INR) للتأكد من أن الجرعة المأخوذة لا تزال آمنة.[2]

Warfarin is a synthetic derivative of dicoumarol, a 4-hydroxycoumarin-derived mycotoxin anticoagulant found in spoiled clover-based animal feeds. Dicoumarol, in turn, is derived from coumarin, a chemical found naturally in many plants. Coumarin, not to be confused with Coumadin, a brand name for warfarin, itself has no effect on clotting, or upon the action of warfarin. Warfarin and related 4-hydroxycoumarin-containing molecules decrease blood coagulation by inhibiting vitamin K epoxide reductase, an enzyme that recycles oxidized vitamin K to its reduced form after it has participated in the carboxylation of several blood coagulation proteins, mainly prothrombin and factor VII. For this reason, drugs in this class are also referred to as vitamin K antagonists.[2]

The name warfarin stems from the acronym for the organization which funded the key research, WARF, for Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation + the ending -arin indicating its link with coumarin.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التاريخ

في 1920 في وقت مبكر ، كان هناك اندلاع لوباء في الماشية غير معروف من قبل في شمال الولايات المتحدة وكندا. وكانت الماشية تنزف بعد إجراءات جراحية بسيطة ، وفى بعض المناسبات ، من تلقاء أنفسهم. وعلى سبيل المثال ، توفي 21 من أصل 22 بعد dehorning للأبقار ، و 12 من أصل 25 من الثيران توفي بعد إخصائهم. وقد نزفت كل هذه الحيوانات حتى الموت.[3] في عام 1921 ، فرانك سكوفيلد ، وهو بيطرى كندى متخصص في علم الامراض للماشية، قرر أن الأبقار تناولت عفن السيلاج المصنوع من sweet clover والتي تعمل بوصفها مضاد للتخثر قوى. وهى تلوث فقط القش المصنوع من البرسيم الحلو (الذى ينمو في الولايات الشمالية و كندا منذ مطلع القرن العشرين) وهذا العفن هو الذى سبب المرض.[4] سكوفيلد قام بفصل سيقان البرسيم الجيدة وسيقان البرسيم المتضررة من القش نفسه قد جزت أو قطعت، وقام بتغذية أرانب مختلفة. الأرانب التى تناولت سيقان لبرسيم الجيدة ظلت في حالة جيدة، ولكن الأرانب التي تناولت السيقان المصابة تضررت وتوفيت من مرض نزفى. وقام بتكرار التجربة مع عينة مختلفة من القش والبرسيم فأعطت نفس النتيجة.[3] في 1929, أظهر البيطري الدكتور رودريك من داكوتا الشمالية أظهر أن تلك الحالة ترجع إلى عدم وجود عامل [البروثرومبين]] .[5] وظلت هوية المادة المضادة للتخثر في البرسيم الحلو الملوث ظلت لغزا حتى عام 1940. وفي عام 1933 , فإن كارل بول لينك ومساعدوه من الكيميائيين العاملين في جامعة ويسكونسن ماديسون قد بدأو في عزل وتحديد خصائص المادة المسببة للنزف من القش الملوث.

وقد إستغرق الأمر خمس سنوات من أحد طلاب لينك ويدعى هارولد .أ كامبيل , كى يمكنه إستخلاص 6 ملليجرامات من مادة بلورية مضادة للتجلط 6&.وفيما بعد تمكن طالب آخر يدعى مارك .ا ستاهمان تولى المشروع وشرع في عملية استخراج واسعة النطاق ، وعزل 1.8 غرام من مادة أعيد بلورتها مضادة للتخثر في حوالي 4 أشهر. وكانت تلك الكمية من المادة كافية كى يواجه ستاهمان وتشارلز .ف هيوبنر إدعاءات كامبيل والتركيز بعمق على هوية المركب الجديد، من خلال إختبارات إنحلال . حيث إكتشفو أن , المادة المضادة للتجلط هى 3,3'-methylenebis-(4-hydroxycoumarin), التى أطلق عليها فيما بعد dicoumarol أو داى كومارول واكدو نتائجهم عن طريق تخليق dicumarol وثبت في عام 1940 أنه كان مطابقا للمركب المتواجد بشكل طبيعي .[6]

Coumarins are now known to be present in many plants, and to produce the notably sweet smell of freshly cut grass or hay.[3] They are present notably in woodruff (Galium odoratum, Rubiaceae), and at lower levels in licorice, lavender, and various other species. However, they themselves do not influence clotting, but must be metabolized by various fungi into compounds such as 4-hydroxycoumarin, then further (in the presence of naturally occurring formaldehyde) into dicoumarol, in order to have anticoagulant properties. Fungal attack of the damaged and dying clover stalks explained the presence of the anticoagulant only in spoiled clover silages; dicoumarol is considered to be a fermentation product and mycotoxin.[7]

Over the next few years, numerous similar chemicals (specifically 4-hydroxycoumarins with a large aromatic substitutent at the 3' position) were found to have the same anticoagulant properties. The first drug in the class to be widely commercialized was dicoumarol itself, patented in 1941 and later used as a pharmaceutical. Karl Link continued working on developing more potent coumarin-based anticoagulants for use as rodent poisons, resulting in warfarin in 1948. The name warfarin stems from the acronym WARF, for Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation + the ending -arin indicating its link with coumarin. Warfarin was first registered for use as a rodenticide in the US in 1948, and was immediately popular; although it was developed by Link, the WARF financially supported the research and was assigned the patent.[8]

بعد حادثة في 1951، حاول فيها مجند في الجيش الأمريكي الانتحار بجرعات عدة من الوارفارين في مبيدات القوارض وتعافى بشكل كامل بعد نقله للمستشفى وعلاجه بڤيتامين ك (وكان يـُعرف آنئذ كترياق محدد)،[8] بدأت الدراسات عن استخدام الوارفارين كمضاد علاجي للتخثر. It was found to be generally superior to dicoumarol, and in 1954 was approved for medical use in humans. A famous early recipient of warfarin was US president دوايت أيزنهاور, who was prescribed the drug after having a heart attack in 1955.[8]

The exact mechanism of action remained unknown until it was demonstrated, in 1978, that warfarin inhibits the enzyme epoxide reductase and hence interferes with vitamin K metabolism.[9]

A 2003 theory posits that warfarin was used by a conspiracy of Lavrenty Beria, Nikita Khrushchev and others to poison Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. Warfarin is tasteless and colorless, and produces symptoms similar to those that Stalin exhibited.[10]

الاستخدامات العلاجية

يوصف الوارفارين للأشخاص المعرضين للخثارات أو كمعالجة وقائية ثانوية (للوقاية من حوادث عرضية أخرى) لدى الأفراد الذين تعرضوا لتشكل خثرة دموية مسبقاً. تساعد المعالجة بالوارفارين في منع تشكل خثرات دموية مستقبلاً وتساعد في إقلال خطر حدوث انصمامات (هجرة الخثرة إلى مكان فتمنع وصول التروية الدموية لأحد الأعضاء الحيوية)

The type of anticoagulation (clot formation inhibition) for which warfarin is best suited, is that in areas of slowly-running blood, such as in veins and the pooled blood behind artificial and natural valves, and pooled in disfunctional cardiac artria. Thus, common clinical indications for warfarin use are atrial fibrillation, the presence of artificial heart valves, deep venous thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism (where the embolized clots first form in veins). Warfarin is also used in antiphospholipid syndrome. It has been used occasionally after heart attacks (myocardial infarction), but is far less effective at preventing new thromboses in coronary arteries. Prevention of clotting in arteries is usually undertaken with antiplatelet drugs, which act by a different mechanism from warfarin (which normally has no effect on platelet function).[11]

Dosing of warfarin is complicated by the fact that it is known to interact with many commonly-used medications and even with chemicals that may be present in certain foods.[1] These interactions may enhance or reduce warfarin's anticoagulation effect. In order to optimize the therapeutic effect without risking dangerous side effects such as bleeding, close monitoring of the degree of anticoagulation is required by blood testing (INR). During the initial stage of treatment, checking may be required daily; intervals between tests can be lengthened if the patient manages stable therapeutic INR levels on an unchanged warfarin dose.[11]

When initiating warfarin therapy ("warfarinization"), the doctor will decide how strong the anticoagulant therapy needs to be. The target INR level will vary from case to case depending on the clinical indicators, but tends to be 2–3 in most conditions. In particular, target INR may be 2.5–3.5 (or even 3.0–4.5) in patients with one or more mechanical heart valves.[12]

In some countries, other coumarins are used instead of warfarin, such as acenocoumarol and phenprocoumon. These have a shorter (acenocoumarol) or longer (phenprocoumon) half-life, and are not completely interchangeable with warfarin. The oral anticoagulant ximelagatran (trade name Exanta) was expected to replace warfarin to a large degree when introduced; however, reports of hepatotoxicity (liver damage) prompted its manufacturer to withdraw it from further development. Other drugs offering the efficacy of warfarin without a need for monitoring, such as dabigatran and rivaroxaban, are under development.[13]

مضادات الاستطباب

الحمل

يعد تناول الوارفارين مضاد استطباب لدى لحوامل لأنه يعبر الحاجز المشيمي وبالتالي ممكن أن يسبب النزف لدى الجنين، ويرتبط استخدام الوارفارين أثناء الحمل بجدوث الإجهاض والإملاص (ولادة ولد ميت) و موت الجنين أو ولادته قبل أوانه.[14]. تعتبر الكومارينات (كالوارفارين) مواد ماسخة - تسبب تشوّه الأجنة- فنسبة حدوث تشوه ولادي لدى الأطفال المعرضين للوارفارين في الرحم حوالي 5%، وظهرت نسبة تجاوزت 30% في بعض الدراسات. [15]

Depending on when exposure occurs during pregnancy, two distinct combinations of congenital abnormalities can arise.[14]

When warfarin (or another coumarin derivative) is given during the first trimester—particularly between the sixth and ninth weeks of pregnancy—a constellation of birth defects known variously as fetal warfarin syndrome (FWS), warfarin embryopathy, or coumarin embryopathy can occur. FWS is characterized mainly by skeletal abnormalities, which include nasal hypoplasia, a depressed or narrowed nasal bridge, scoliosis, and calcifications in the vertebral column, femur, and heel bone which show a peculiar stippled appearance on X-rays. Limb abnormalities, such as brachydactyly (unusually short fingers and toes) or underdeveloped extremities, can also occur.[14][15] Common non-skeletal features of FWS include low birth weight and developmental disabilities.[14][15]

Warfarin administration in the second and third trimesters is much less commonly associated with birth defects, and when they do occur, are considerably different from fetal warfarin syndrome. The most common congenital abnormalities associated with warfarin use in late pregnancy are central nervous system disorders, including spasticity and seizures, and eye defects.[14][15] Because of such later pregnancy birth defects, anticoagulation with warfarin poses a problem in pregnant women requiring warfarin for vital indications, such as stroke prevention in those with artificial heart valves. Usually, warfarin is avoided in the first trimester, and a low molecular weight heparin such as enoxaparin is substituted. With heparin, risk of maternal hemorrhage and other complications is still increased, but heparins do not cross the placental barrier and therefore do not cause birth defects.[15] Various solutions exist for the time around delivery.

التأثيرات الضائرة

النزف

إن النزف هو التأثير الجانبي الوحيد الشائع للوارفارين. وتعد خطورة النزف الشديد صغيرة لكنها ممكنة، سجّل المعدل السنوي الوسطي بـ 0.9 إلى 2.7 % [16]). تزداد خطورة النزف عندما تزداد قيمة INR (عند تناول جرعة مفرطة عمداً أو دون قصد أو عند حدوث تآثرات دوائية تزيد من تركيزه الدموي) مما قد يسبب نفث الدم ظهور الكدمات أو نزوف الأنف واللثة أو ظهور دم في بول المريض أو برازه.

تزداد مخاطر حدوث النزف عندما يتناول المريض أدوية أخرى مضادة لتكدّس الصفيحات مع الوارفارين كالكلوپيدوگريل والأسبرين أو أي من مضادات الالتهاب اللاستيروئيدية الأخرى.[17] وتزداد الخطورة أيضاًلدى المسنين [18] ولدى مرضى التحال الدموي.[19]

التنخر بسبب الوارفارين

مقالة مفصلة: التنخر بسبب الوارفارين

مقالة مفصلة: التنخر بسبب الوارفارين

وهو اختلاط نادر لكن خطير يحدث عادةً بعد البدء بمعالجة مرضى لديهم عوز بالبروتين C. فالبروتين C هو مضاد تخثر خلقي مثل طلائع التخثر التي يثبطها الورافارين ويحتاج لكرسلة معتمدة على الفيتامين ك لتنشيطه.

Since warfarin initially decreases protein C levels faster than the coagulation factors, it can paradoxically increase the blood's tendency to coagulate when treatment is first begun (many patients when starting on warfarin are given heparin in parallel to combat this), leading to massive thrombosis with skin necrosis and gangrene of limbs. Its natural counterpart, purpura fulminans, occurs in children who are homozygous for certain protein C mutations.[20]

تخلخل العظام

بيّنت التقارير الأولية أن الوارفارين يسبّب انخفاض الكثافة العظمية وقد أشارت العديد من الدراسات إلى وجود ارتباط بين استخدام الوارفارين و حدوث الكسور المرتبطة بتخلخل العظام. وفي دراسة جرت عام 1999 على 572 امرأة يتناولون الوارفارين لحالات الخثار الوريدي العميق، تزايدت خطورة الإصابة بكسور فقرية وبالأضلاع ولم تظهر أنواع أخرى من الكسور بشكل شائع.[21] وفي دراسة جرت في عام 2002 على عينة تم اختيارها عشوائياً من أصل 1523 مريض مصاب بكسور متعلّقة بتخلخل العظام لم يظهر ارتفاع في التعرّض لمضادات التخثر مقارنة بالشواهد ولم تظهر مطابقة بمدة الفعل المضاد للتخثر مظهرةً ميلاً تجاه حدوث كسور.[22]

وفي دراسة استعادية جرت عام 2006 على 14,564 مريض مسنّ أظهرت أنّ الوارفارين المستخدم لمدة تتجاوز العام يرتبط بتزايد خطر الإصابة بالكسور المتعلقة بتخلخل العظام بنسبة 60% لدى الرجال، ولم تلاحظ أية علاقة بذلك لدى النساء. وقد ساد الاعتقاد بأن الآلية كانت مزيج من تناقص تناول الفيتامين K الضروري لسلامة العظام ومنع الوارفارين للكرسلةالمتواسطة بالفيتامين K لبعض البروتينات العظمية محوّلة إياها لبروتينات غير فعّالة.[23]

Purple toe syndrome

Another rare complication that may occur early during warfarin treatment (usually within 3 to 8 weeks) is purple toe syndrome. This condition is thought to result from small deposits of cholesterol breaking loose and flowing into the blood vessels in the skin of the feet, which causes a blueish purple color and may be painful. It is typically thought to affect the big toe, but it affects other parts of the feet as well, including the bottom of the foot (plantar surface). The occurrence of purple toe syndrome may require discontinuation of warfarin.[24]

Pharmacology

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Pharmacokinetics

Warfarin consists of a racemic mixture of two active enantiomers—R- and S- forms—each of which is cleared by different pathways. S-warfarin has five times the potency of the R-isomer with respect to vitamin K antagonism.[11]

Warfarin is slower-acting than the common anticoagulant heparin, though it has a number of advantages. Heparin must be given by injection, whereas warfarin is available orally. Warfarin has a long half-life and need only be given once a day. Heparin can also cause a prothrombotic condition, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (an antibody-mediated decrease in platelet levels), which increases the risk for thrombosis. It takes several days for Warfarin to reach the therapeutic effect since the circulating coagulation factors are not affected by the drug (thrombin has a half-life time of days). Warfarin's long half life means that it remains effective for several days after it was stopped. Furthermore, if given initially without additional anticoagulant cover, it can increase thrombosis risk (see below). For these main reasons, hospitalised patients are usually given heparin with warfarin initially, the heparin covering the 3-5 day lag period and being withdrawn after a few days.

آلية العمل

Warfarin inhibits the vitamin K-dependent synthesis of biologically active forms of the calcium-dependent clotting factors II, VII, IX and X, as well as the regulatory factors protein C, protein S, and protein Z.[2][25] Other proteins not involved in blood clotting, such as osteocalcin, or matrix Gla protein, may also be affected.

The precursors of these factors require carboxylation of their glutamic acid residues to allow the coagulation factors to bind to phospholipid surfaces inside blood vessels, on the vascular endothelium. The enzyme that carries out the carboxylation of glutamic acid is gamma-glutamyl carboxylase. The carboxylation reaction will proceed only if the carboxylase enzyme is able to convert a reduced form of vitamin K (vitamin K hydroquinone) to vitamin K epoxide at the same time. The vitamin K epoxide is in turn recycled back to vitamin K and vitamin K hydroquinone by another enzyme, the vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKOR). Warfarin inhibits epoxide reductase[9] (specifically the VKORC1 subunit[26][27]), thereby diminishing available vitamin K and vitamin K hydroquinone in the tissues, which inhibits the carboxylation activity of the glutamyl carboxylase. When this occurs, the coagulation factors are no longer carboxylated at certain glutamic acid residues, and are incapable of binding to the endothelial surface of blood vessels, and are thus biologically inactive. As the body's stores of previously-produced active factors degrade (over several days) and are replaced by inactive factors, the anticoagulation effect becomes apparent. The coagulation factors are produced, but have decreased functionality due to undercarboxylation; they are collectively referred to as PIVKAs (proteins induced [by] vitamin K absence/antagonism), and individual coagulation factors as PIVKA-number (e.g. PIVKA-II). The end result of warfarin use, therefore, is to diminish blood clotting in the patient.

When warfarin is newly started, it may promote clot formation temporarily. This is because the level of protein C and protein S are also dependent on vitamin K activity. Warfarin causes decline in protein C levels in first 36 hours. In addition, reduced levels of protein S lead to a reduction in activity of protein C (for which it is the co-factor) and therefore reduced degradation of factor Va and factor VIIIa. Although loading doses of warfarin over 5 mg also produce a precipitous decline in factor VII, resulting in an initial prolongation of the INR, full antithrombotic effect does not take place until significant reduction in factor II occurs days later. The hemostasis system becomes temporarily biased towards thrombus formation, leading to a prothrombotic state. Thus, when warfarin is loaded rapidly at greater than 5 mg per day, it is beneficial to co-administer heparin, an anticoagulant that acts upon antithrombin and helps reduce the risk of thrombosis, with warfarin therapy for four to five days, in order to have the benefit of anticoagulation from heparin until the full effect of warfarin has been achieved.[28][29]

Antagonism

The effects of warfarin can be reversed with vitamin K, or, when rapid reversal is needed (such as in case of severe bleeding), with prothrombin complex concentrate—which contains only the factors inhibited by warfarin—or fresh frozen plasma (depending upon the clinical indication) in addition to intravenous vitamin K.

Details on reversing warfarin are provided in clinical practice guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians.[30] For patients with an international normalized ratio (INR) between 4.5 and 10.0, a small dose of oral vitamin K is sufficient.[31]

Pharmacogenomics

Warfarin activity is determined partially by genetic factors. The American Food and Drug Administration "highlights the opportunity for healthcare providers to use genetic tests to improve their initial estimate of what is a reasonable warfarin dose for individual patients".[32] Polymorphisms in two genes (VKORC1 and CYP2C9) are particularly important.

VKORC1 polymorphisms explain 30% of the dose variation between patients:[33] particular mutations make VKORC1 less susceptible to suppression by warfarin.[27] There are two main haplotypes that explain 25% of variation: low-dose haplotype group (A) and a high-dose haplotype group (B).[34] VKORC1 polymorphisms explain why African Americans are on average relatively resistant to warfarin (higher proportion of group B haplotypes), while Asian Americans are generally more sensitive (higher proportion of group A haplotypes).[34] Group A VKORC1 polymorphisms lead to a more rapid achievement of a therapeutic INR, but also a shorter time to reach an INR over 4, which is associated with bleeding.[35]

CYP2C9 polymorphisms explain 10% of the dose variation between patients,[33] mainly among Caucasian patients as these variants are rare in African American and most Asian populations.[36] These CYP2C9 polymorphisms do not influence time to effective INR as opposed to VKORC1, but does shorten the time to INR >4.[35]

Loading regimens

Because of warfarin's poorly-predictable pharmacokinetics, several researchers have proposed algorithms for commencing warfarin treatment:

- The Kovacs 10 mg algorithm was better than a 5 mg algorithm.[37]

- The Fennerty 10 mg regimen is for urgent anticoagulation[38]

- The Tait 5 mg regimen is for "routine" (low-risk) anticoagulation[39]

- From a cohort of orthopedic patients, Millican et al. derived an 8-value model, including CYP29C and VKORC1 genotype results, that could predict 79% of the variation in warfarin doses. It is awaiting validation in larger populations and has not been reproduced in those who require warfarin for other indications.[40]

- Lenzini et al. derived and prospectively validated a model including CYP29C and VKORC1 genotypes. This model could predict 70% of the variation in warfarin doses in a validation cohort (versus 48% without genotype). The pharmacogenetic protocol lead to a reduction in out of range INR values as compared to a historic control.[41]

- www.WarfarinDosing.org, is a non-profit website programmed with dosing calculators and other decision support tools for clinicians' use when initiating warfarin therapy.[42]

ضبط جرعة الصيانة

Recommendations by many national bodies including the American College of Chest Physicians[30] have been distilled to help manage dose adjustments.[43]

Self-testing and home monitoring

Patients are making increasing use of self-testing and home monitoring of oral anticoagulation. International guidelines were published in 2005 to govern home testing, by the International Self-Monitoring Association for Oral Anticoagulation.[44]

The international guidelines study stated: "The consensus agrees that patient self-testing and patient self-management are effective methods of monitoring oral anticoagulation therapy, providing outcomes at least as good as, and possibly better than, those achieved with an anticoagulation clinic. All patients must be appropriately selected and trained. Currently-available self-testing/self-management devices give INR results that are comparable with those obtained in laboratory testing."[2]

تفاعلات الدواء

يتداخل الوارفارين مع العديد من الأدوية شائعة الاستخدام ويختلف استقلاب الوارفارين بين المرضى. وقد سجلت بعض التداخلات بين بعض الأطعمة والوارفارين[1] وبعيداً عن التداخلات (التآثرات) الاستقلابية فإن الأدوية شديدة الارتباط بالبروتين تزيح الوارفارين من أماكن ارتباطه على الألبومين المصلي مسبباً تزايد في قيم الـ INR.[45] وهذا ما يسبب صعوبة في إيجاد الجرعة الموجودة ويؤكد على ضرورة المراقبة عند تناول دواء معروف بتداخله مع الوارفارين (مثل السيمڤاستاتين

Many commonly-used antibiotics, such as metronidazole or the macrolides, will greatly increase the effect of warfarin by reducing the metabolism of warfarin in the body. Other broad-spectrum antibiotics can reduce the amount of the normal bacterial flora in the bowel, which make significant quantities of vitamin K, thus potentiating the effect of warfarin.[46] In addition, food that contains large quantities of vitamin K will reduce the warfarin effect.[1] Thyroid activity also appears to influence warfarin dosing requirements;[47] hypothyroidism (decreased thyroid function) makes people less responsive to warfarin treatment,[48] while hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid) boosts the anticoagulant effect.[49] Several mechanisms have been proposed for this effect, including changes in the rate of breakdown of clotting factors and changes in the metabolism of warfarin.[47][50]

كما أن تناول كميات كبيرة من الكحول يؤثر على استقلاب الوارفارين ويؤدي إلى ارتفاع قيم INR. ا[51] لذلك يتم تحذير المرضى من تناول كميات كبيرة من الكحول فترة تناولهم للوارفارين.

Warfarin also interacts with many herbs and spices,[52] some used in food (such as ginger and garlic) and others used purely for medicinal purposes (such as ginseng and Ginkgo biloba). All may increase bleeding and brusing in people taking warfarin; similar effects have been reported with borage (starflower) oil or fish oils.[53] St. John's Wort, sometimes recommended to help with mild to moderate depression, interacts with warfarin; it induces the enzymes that break down warfarin in the body, causing a reduced anticoagulant effect.[54]

Between 2003 and 2004, the UK Committee on Safety of Medicines received several reports of increased INR and risk of hemorrhage in people taking warfarin and cranberry juice.[55][56][57] Data establishing a causal relationship is still lacking, and a 2006 review found no cases of this interaction reported to the FDA;[57] nevertheless, several authors have recommended that both doctors and patients be made aware of its possibility.[58] The mechanism behind the interaction is still unclear.[57]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الاستخدام كمبيد حشري

To this day, coumarins are used as rodenticides for controlling rats and mice in residential, industrial, and agricultural areas. Warfarin is both odorless and tasteless, and is effective when mixed with food bait, because the rodents will return to the bait and continue to feed over a period of days until a lethal dose is accumulated (considered to be 1 mg/kg/day over about six days). It may also be mixed with talc and used as a tracking powder, which accumulates on the animal's skin and fur, and is subsequently consumed during grooming. The LD50 is 50–500 mg/kg. The IDLH value is 100 mg/m³ (warfarin; various species).[59]

The use of warfarin as a rat poison is now declining because many rat populations have developed resistance to it, and poisons of considerably greater potency are now available. Other coumarins used as rodenticides include coumatetralyl and brodifacoum, which is sometimes referred to as "super-warfarin", because it is more potent, longer-acting, and effective even in rat and mouse populations that are resistant to warfarin. Unlike warfarin, which is readily excreted, newer anticoagulant poisons also accumulate in the liver and kidneys after ingestion.[60]

التصنيع الكيميائي

The succinct synthesis of warfarin starts with condensation of ortho-hydroxyacetophenone (1-2) with ethyl carbonate to give the b-ketoester as the intermediate shown in the enol form. Attack of the phenoxide on the ester grouping leads to cyclization and formation of the coumarin. Conjugate addition of the anion from that product to methyl styryl ketone gives the corresponding Michael adduct and thus warfarin.[61]

الهامش

- ^ أ ب ت ث Holbrook AM, Pereira JA, Labiris R; et al. (2005). "Systematic overview of warfarin and its drug and food interactions". Arch. Intern. Med. 165 (10): 1095–106. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.10.1095. PMID 15911722.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب ت ث Ansell J, Hirsh J, Poller L, Bussey H, Jacobson A, Hylek E (2004). [http://www.chestjournal.org/cgi/content/full/126

/3_suppl/204S "The pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy"]. Chest. 126 (3 Suppl): 204S–233S. doi:10.1378/chest.126.3_suppl.204S. PMID 15383473.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help); line feed character in|url=at position 49 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب ت Laurence, D.R. (1973). Clinical Pharmacology. Peter Kneebone. Edinburgh, London and New York: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 23.4–23.5. ISBN 0443049904.

- ^ Schofield FW (1924). "Damaged sweet clover; السبب cause of a new disease in cattle simulating haemorrhagic septicemia and blackleg". J Am Vet Med Ass. 64: 553–6.

- ^ Roderick LM (1931). "A problem in the coagulation of the blood; "sweet clover disease of the cattle"". Am J Physiol. 96: 413–6. PDF (subscriber only).

- ^ Stahmann MA, Huebner CF, Link KP (1 April 1941). "Studies on the hemorrhagic sweet clover المتسبب في حوادث موت الماشية. V. Identification and synthesis of the hemorrhagic agent". J Biol Chem. 138 (2): 513–27.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bye, A., King, H. K., 1970. The biosynthesis of 4-hydroxycoumarin and dicoumarol by Aspergillus fumigatus Fresenius. Biochemical Journal 117, 237-245.

- ^ أ ب ت Link KP (1 January 1959). "The discovery of dicumarol and its sequels". Circulation. 19 (1): 97–107. PMID 13619027.

- ^ أ ب Whitlon DS, Sadowski JA, Suttie JW (1978). "Mechanism of coumarin action: significance of vitamin K epoxide reductase inhibition". Biochemistry. 17 (8): 1371–7. doi:10.1021/bi00601a003. PMID 646989.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Naumov, Vladimir Pavlovich; Brent, Jonathan (2003). Stalin's last crime: the plot against the Jewish doctors, 1948–1953. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-019524-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب ت Hirsh J, Fuster V, Ansell J, Halperin JL (2003). "American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation guide to warfarin therapy". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 41 (9): 1633–52. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00416-9. PMID 12742309.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baglin TP, Keeling DM, Watson HG (2006). "Guidelines on oral anticoagulation (warfarin): third edition—2005 update". Br. J. Haematol. 132 (3): 277–85. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05856.x. PMID 16409292.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hirsh J, O'Donnell M, Eikelboom JW (2007). "Beyond unfractionated heparin and warfarin: current and future advances". Circulation. 116 (5): 552–60. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685974. PMID 17664384.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب ت ث ج Macina, Orest T.; Schardein, James L. (2007). "Warfarin". Human Developmental Toxicants. Boca Raton: CRC Taylor & Francis. pp. 193–4. ISBN 0-8493-7229-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Retrieved on December 15, 2008 through Google Book Search. - ^ أ ب ت ث ج Loftus, Christopher M. (1995). "Fetal toxicity of common neurosurgical drugs". Neurosurgical Aspects of Pregnancy. Park Ridge, Ill: American Association of Neurological Surgeons. pp. 11–3. ISBN 1-879284-36-7.

- ^ Horton JD, Bushwick BM (1999). "Warfarin therapy: evolving strategies in anticoagulation". Am Fam Physician. 59 (3): 635–46. PMID 10029789.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Delaney JA, Opatrny L, Brophy JM, Suissa S (2007). "Drug drug interactions between antithrombotic medications and the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding". CMAJ. 177 (4): 347–51. doi:10.1503/cmaj.070186. PMC 1942107. PMID 17698822.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) قالب:PMC - ^ Hylek EM, Evans-Molina C, Shea C, Henault LE, Regan S (2007). "Major hemorrhage and tolerability of warfarin in the first year of therapy among elderly patients with atrial fibrillation". Circulation. 115 (21): 2689–96. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.653048. PMID 17515465.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Elliott MJ, Zimmerman D, Holden RM (2007). "Warfarin anticoagulation in hemodialysis patients: a systematic review of bleeding rates". Am. J. Kidney Dis. 50 (3): 433–40. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.06.017. PMID 17720522.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chan YC, Valenti D, Mansfield AO, Stansby G (2000). "Warfarin induced skin necrosis". Br J Surg. 87 (3): 266–72. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01352.x. PMID 10718793.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Caraballo PJ, Heit JA, Atkinson EJ; et al. (1999). "Long-term use of oral anticoagulants and the risk of fracture". Arch. Intern. Med. 159 (15): 1750–6. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.15.1750. PMID 10448778.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pilon D, Castilloux AM, Dorais M, LeLorier J (2004). "Oral anticoagulants and the risk of osteoporotic fractures among elderly". Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 13 (5): 289–94. doi:10.1002/pds.888. PMID 15133779.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gage BF, Birman-Deych E, Radford MJ, Nilasena DS, Binder EF (2006). "Risk of osteoporotic fracture in elderly patients taking warfarin: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation 2". Arch. Intern. Med. 166 (2): 241–6. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.2.241. PMID 16432096.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Talmadge DB, Spyropoulos AC (2003). "Purple toes syndrome associated with warfarin therapy in a patient with antiphospholipid syndrome". Pharmacotherapy. 23 (5): 674–7. doi:10.1592/phco.23.5.674.32200. PMID 12741443.

- ^ Freedman MD (1992). "Oral anticoagulants: pharmacodynamics, clinical indications and adverse effects". J Clin Pharmacol. 32 (3): 196–209. PMID 1564123.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Li T, Chang CY, Jin DY, Lin PJ, Khvorova A, Stafford DW (2004). "Identification of the gene for vitamin K epoxide reductase". Nature. 427 (6974): 541–4. doi:10.1038/nature02254. PMID 14765195.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب Rost S, Fregin A, Ivaskevicius V; et al. (2004). "Mutations in VKORC1 cause warfarin resistance and multiple coagulation factor deficiency type 2". Nature. 427 (6974): 537–41. doi:10.1038/nature02214. PMID 14765194.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Litin SC, Gastineau DA (1995). "Current concepts in anticoagulant therapy". Mayo Clin. Proc. 70 (3): 266–72. doi:10.4065/70.3.266. PMID 7861815.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wittkowsky AK (2005). "Why warfarin and heparin need to overlap when treating acute venous thromboembolism". Dis Mon. 51 (2–3): 112–5. doi:10.1016/j.disamonth.2005.03.005. PMID 15900262.

- ^ أ ب Ansell J, Hirsh J, Poller L, Bussey H, Jacobson A, Hylek E (2004). "The pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy". Chest. 126 (3 Suppl): 204S–233S. doi:10.1378/chest.126.3_suppl.204S. PMID 15383473.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (summary) - ^ Crowther MA, Douketis JD, Schnurr T; et al. (2002). "Oral vitamin K lowers the international normalized ratio more rapidly than subcutaneous vitamin K in the treatment of warfarin-associated coagulopathy. A randomized, controlled trial" (PDF). Ann. Intern. Med. 137 (4): 251–4. PMID 12186515.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "FDA Approves Updated Warfarin (Coumadin) Prescribing Information". Retrieved 2009-08-04.

- ^ أ ب Wadelius M, Chen LY, Downes K; et al. (2005). "Common VKORC1 and GGCX polymorphisms associated with warfarin dose". Pharmacogenomics J. 5 (4): 262–70. doi:10.1038/sj.tpj.6500313. PMID 15883587.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب Rieder MJ, Reiner AP, Gage BF; et al. (2005). "Effect of VKORC1 haplotypes on transcriptional regulation and warfarin dose". N. Engl. J. Med. 352 (22): 2285–93. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa044503. PMID 15930419.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب Schwarz UI, Ritchie MD, Bradford Y; et al. (2008). "Genetic determinants of response to warfarin during initial anticoagulation". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (10): 999–1008. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0708078. PMID 18322281.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sanderson S, Emery J, Higgins J (2005). "CYP2C9 gene variants, drug dose, and bleeding risk in warfarin-treated patients: a HuGEnet systematic review and meta-analysis". Genet. Med. 7 (2): 97–104. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.30391. PMID 15714076.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kovacs MJ, Rodger M, Anderson DR; et al. (2003). "Comparison of 10-mg and 5-mg warfarin initiation nomograms together with low-molecular-weight heparin for outpatient treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial". Ann. Intern. Med. 138 (9): 714–9. PMID 12729425.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (summary of 10 mg algorithm) - ^ Fennerty A, Campbell IA, Routledge PA (1988). "Anticoagulants in venous thromboembolism". BMJ. 297 (6659): 1285–8. doi:10.1136/bmj.297.6659.1285. PMC 1834928. PMID 3144365.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) قالب:PMC - ^ Tait RC, Sefcick A (1998). "A warfarin induction regimen for out-patient anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation". Br. J. Haematol. 101 (3): 450–4. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00716.x. PMID 9633885. summary

- ^ Millican E, Jacobsen-Lenzini PA, Milligan PE; et al. (2007). "Genetic-based dosing in orthopaedic patients beginning warfarin therapy". Blood. 110 (5): 1511–5. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-01-069609. PMC 1975838. PMID 17387222.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - ^ Lenzini PA, Grice GR, Milligan PE; et al. (2008). "Laboratory and clinical outcomes of pharmacogenetic vs. clinical protocols for warfarin initiation in orthopedic patients". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 6: 1–8. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03095x.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Online tool based on the study. - ^ Online tool based on the study.

- ^ "Point-of-Care Guides: May 15, 2005. American Family Physician". Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- ^ Ansell J, Jacobson A, Levy J, Völler H, Hasenkam JM (2005). "Guidelines for implementation of patient self-testing and patient self-management of oral anticoagulation. International consensus guidelines prepared by International Self-Monitoring Association for Oral Anticoagulation". Int. J. Cardiol. 99 (1): 37–45. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.11.008. PMID 15721497.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gage BF, Fihn SD, White RH (2000). "Management and dosing of warfarin therapy". Am. J. Med. 109 (6): 481–8. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00545-3. PMID 11042238.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Juurlink DN (2007). "Drug interactions with warfarin: what clinicians need to know". CMAJ. 177 (4): 369–71. doi:10.1503/cmaj.070946. PMC 1942100. PMID 17698826.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ أ ب Kurnik D, Loebstein R, Farfel Z, Ezra D, Halkin H, Olchovsky D (2004). "Complex drug-drug-disease interactions between amiodarone, warfarin, and the thyroid gland". Medicine (Baltimore). 83 (2): 107–13. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000123095.65294.34. PMID 15028964.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stephens MA, Self TH, Lancaster D, Nash T (1989). "Hypothyroidism: effect on warfarin anticoagulation". South Med J. 82 (12): 1585–6. PMID 2595433.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chute JP, Ryan CP, Sladek G, Shakir KM (1997). "Exacerbation of warfarin-induced anticoagulation by hyperthyroidism". Endocr Pract. 3 (2): 77–9. PMID 15251480.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kellett HA, Sawers JS, Boulton FE, Cholerton S, Park BK, Toft AD (1986). "Problems of anticoagulation with warfarin in hyperthyroidism". Q J Med. 58 (225): 43–51. PMID 3704105.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Weathermon R, Crabb DW (1999). "Alcohol and medication interactions". Alcohol Res Health. 23 (1): 40–54. PMID 10890797.

- ^ Austin, Steve and Batz, Forrest (1999). Lininger, Schuyler W. (ed.). A-Z guide to drug-herb-vitamin interactions: how to improve your health and avoid problems when using common medications and natural supplements together. Roseville, Calif: Prima Health. p. 224. ISBN 0-7615-1599-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Information Pharmacists' news" (PDF). Information Centre Bulletin. 1 Lambeth High Street, London SE1 7JN: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. 2008. p. 1. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Dr Jo Barnes BPharm MRPharmS (2002). "Herb-medicine interactions: St John's Wort (Hypericum perforatum) Useful information for pharmacist" (PDF). 1 Lambeth High Street, London SE1 7JN: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. p. 5. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Cranberry juice clot drug warning". BBC news. 2003-09-18. Retrieved 2008-05-18.

- ^ Suvarna R, Pirmohamed M, Henderson L (2003). "Possible interaction between warfarin and cranberry juice". BMJ. 327 (7429): 1454. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7429.1454. PMC 300803. PMID 14684645.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب ت Aston JL, Lodolce AE, Shapiro NL (2006). "Interaction between warfarin and cranberry juice". Pharmacotherapy. 26 (9): 1314–9. doi:10.1592/phco.26.9.1314. PMID 16945054.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Free full text with registration at Medscape - ^ Pham DQ, Pham AQ (2007). "Interaction potential between cranberry juice and warfarin". Am J Health Syst Pharm. 64 (5): 490–4. doi:10.2146/ajhp060370. PMID 17322161.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ United States Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) (August 16, 1996). "Documentation for Immediately Dangerous To Life or Health Concentrations (IDLHs): Warfarin". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- ^ Charles T. Eason (2001). "2. Anticoagulant poisons". Vertebrate pesticide toxicology manual (poisons). New Zealand Department of Conservation. pp. 41–74. ISBN 0-478-22035-9.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Blicke, F. F.; Swisher, R. D. (1934). Journal of the American Chemical Society. 56: 902. doi:10.1021/ja01319a042.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

وصلات خارجية

- CS1 errors: invisible characters

- CS1 errors: URL

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 maint: location

- CS1 errors: access-date without URL

- CS1 errors: missing title

- ECHA InfoCard ID from Wikidata

- Infobox-drug molecular-weight unexpected-character

- Pages using infobox drug with unknown parameters

- Articles without EBI source

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without InChI source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugboxes which contain changes to watched fields

- Vitamin K antagonists

- مبيدات قوارض

- Teratogens

- Coumarins